By Sarah Aguiar, Staff Writer

Gender, in itself, never ceases to be a topic of conversation these days. Articles upon articles are written, detailing the supposed blatant discrimination of one gender from the other, either in the workplace, in households or, in particular, schools. The media and the rest of the world have proven that both boys and girls are disadvantaged by the modern educational system: where girls are falling behind the most in STEM and boys in humanities. But the underlying fault of these discrepancies falls upon stereotypes that have, over time, made both humanities and STEM gender specific subjects, and have therefore created a stigma for those who wish to deviate from the “accepted subject” for their gender.

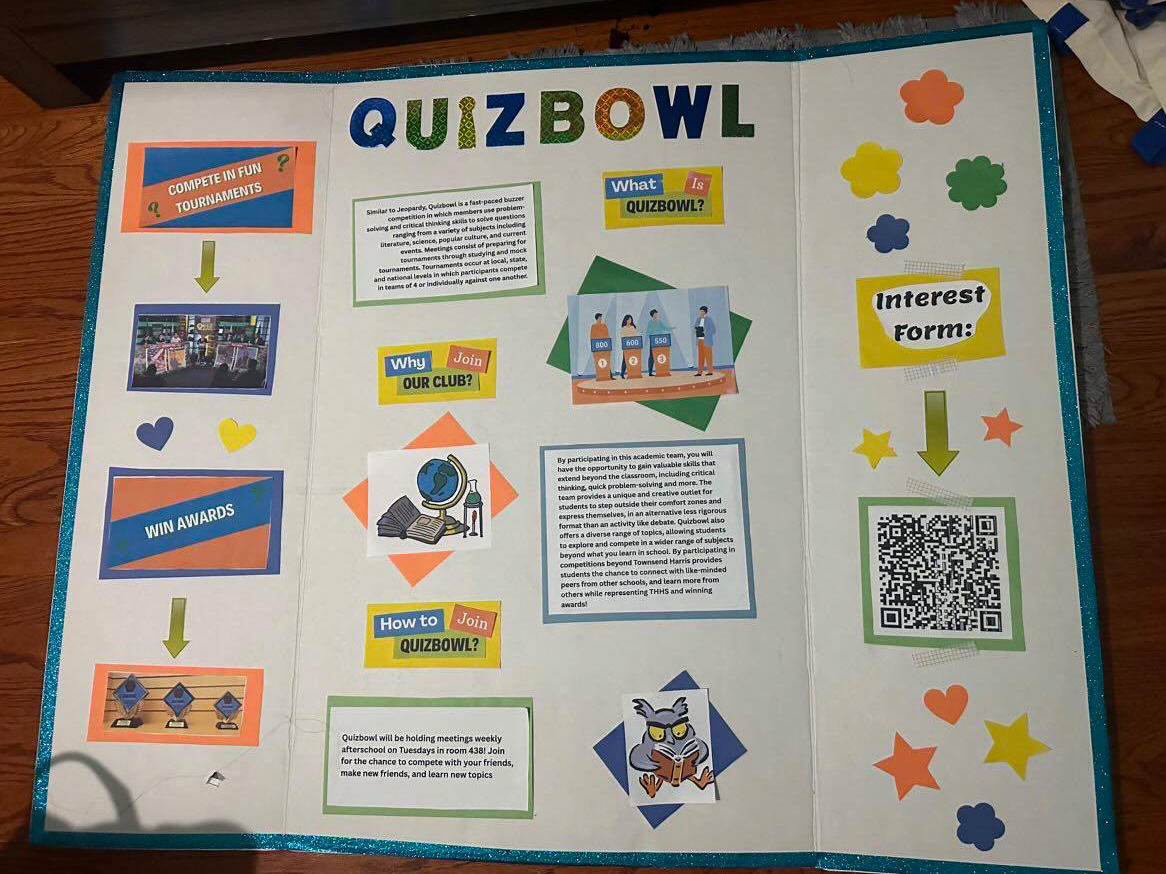

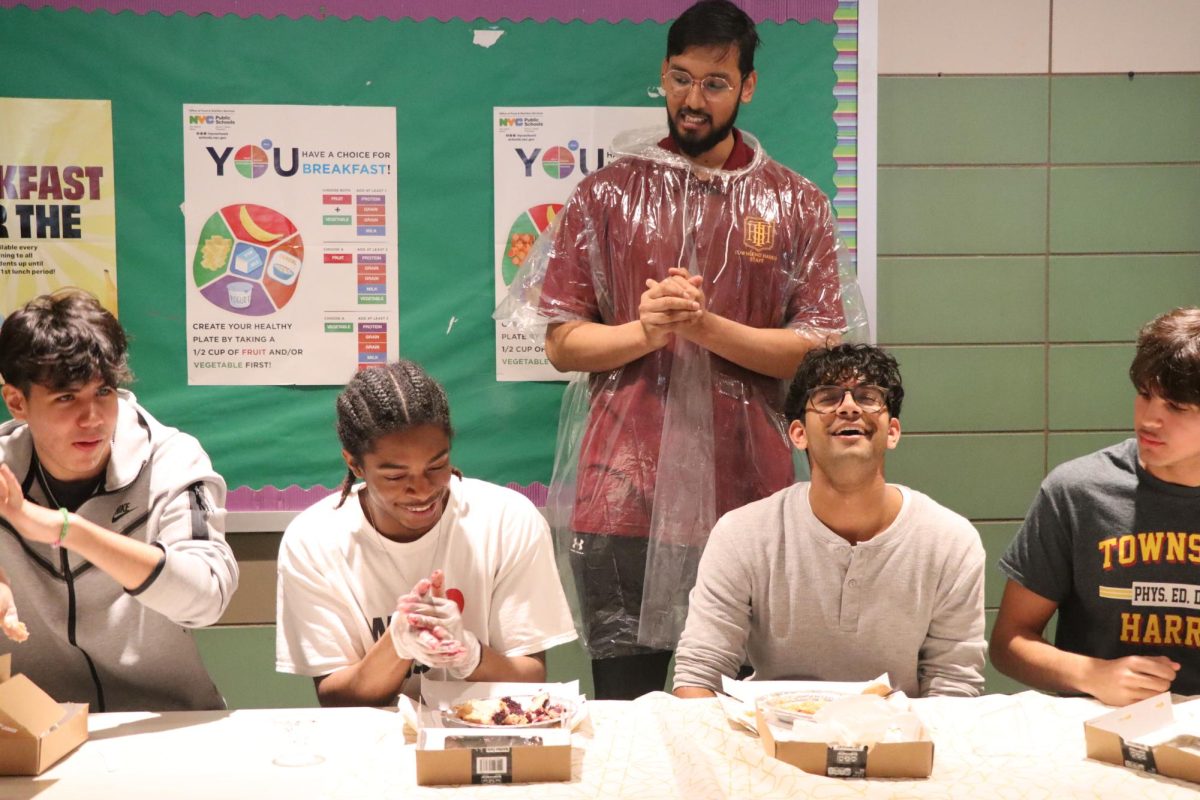

Townsend Harris, a humanities school, is predominantly female. Some may argue this discrepancy exists because “guys just aren’t interested in humanities”, but is this really always the case?

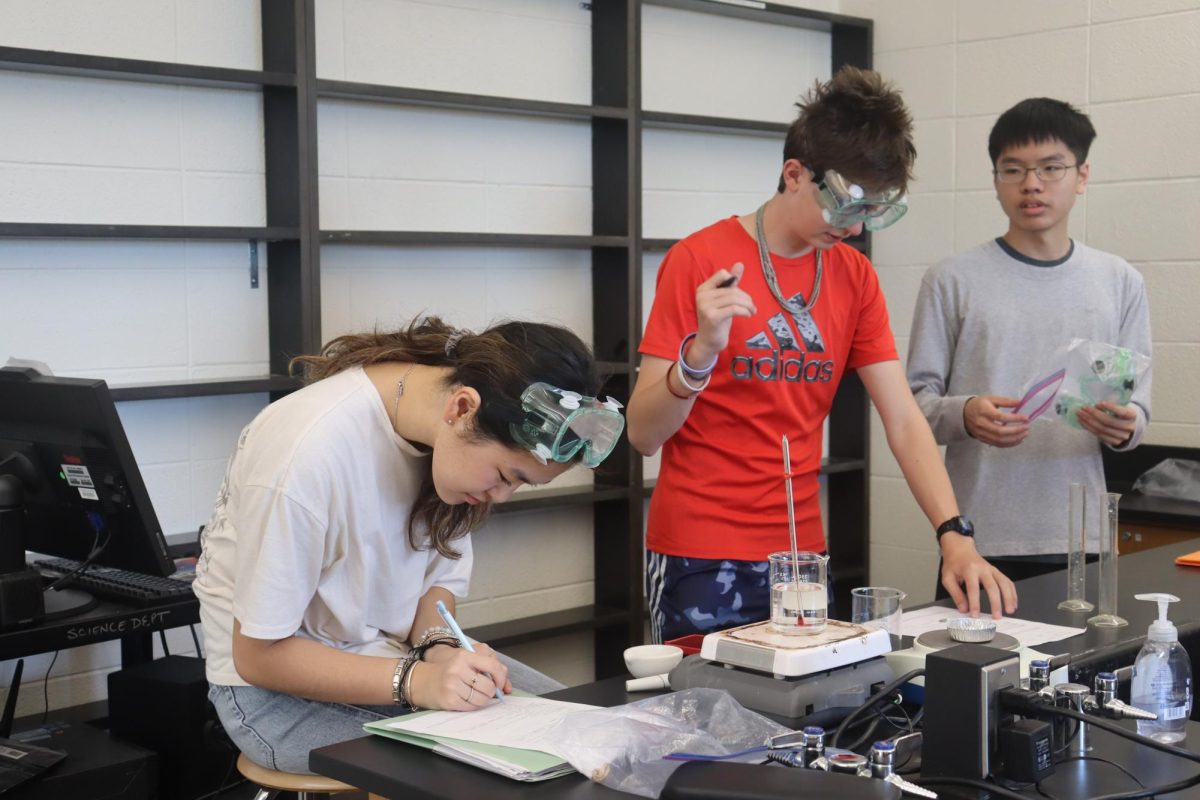

A recent study led by UNSW Sydney Ph.D. student Rose O’Dea tested the grade patterns in about 1.6 million students.They found that both girls and boys perform at similar levels in STEM, a trend existing even at the top percentage of classes. And yet, more boys pursue STEM as a career, while more girls pursue humanities. This exhibits the idea of “social belongingness” – especially when teenagers have even admitted that they would fit better in subjects that are more commonly pursued by people of their own gender. Both girls and boys are taught that they would perform better in subjects that include more of their own respective gender, eliminating the amount of gender competition they experience.

Say, for instance, you’re a girl achieving high grades across the board. You walk into your math class, and it’s dominated by high-achieving boys. However, in your English class, there are fewer boys to compete with, and thus making the non-STEM career path not as daunting. This can also be applied to boys, who see female-dominated fields such as humanities and choose to pursue STEM because of the lack of gender competition existing there. It has become a common trend for people to choose the field they feel they would be most comfortable, not what they know will benefit them.

This comfort around those of our own gender has its roots in stereotypes as well. In Christia S. Brown’s article “The Way We Talk About Gender Can Make a Big Difference,” she writes, “By having teachers simply focus on their gender instead of their individual characteristics, children began to overlook that there were, indeed, individual variations within male or female groups.” Children are taught from a young age that boys and girls must act a certain way. Consequently, they will be uncomfortable around those of the opposite gender because they act differently from them. They are not taught that differences are accepted, and therefore choose to follow their own gender for the sake of not being alienated when, in reality, these distinctions will define who they are in the future.

We live in a society in which paving your own path, diverging from those already taken, is welcomed with open arms. However, this does not seem to be the case with education. Solving such issues will take time, but will require the involvement of people all over the world. We can start by encouraging all to pursue fields they may have premonitions in, exposing them to more of the world. Programs, such as Girls Who Code, Black Girls Code and Girls Develop It, encourage girls of all ages and races to participate more in STEM. The same must be done to support boys who wish to go further in humanities. Programs are not the only way, since role models do play a tremendous part in someone’s life. Students should be exposed to such nonconformists— men in humanities, women in STEM— to help encourage them to be pioneers such as the ones they see changing the world for the better.

Shirley Chisholm, a politician and author, said, “We must reject not only the stereotypes that others have of us but also those that we have of ourselves.” Generalizations have come to govern parts of our lives that have damaged the way we live. They have influenced our decisions, our career choices and our futures. They seem to be one of the only things holding us back from being what we all want to be: free from judgement, free to be ourselves. And if expressing ourselves through our education means breaking through these stereotypes, then so be it.