It is no secret that after the birth of a child, parents often struggle to balance their professional responsibilities with the demands of parenthood. For this reason, many developed nations require that companies guarantee jobs for workers who have children to care for. Unfortunately, when it comes to financially covering women after they give birth, the United States trails behind most other developed nations; this must change.

While the federal Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978 protects women from losing their jobs or being denied employment because of their condition, it does not require that women receive paid time off after giving birth. Thus, amongst industrialized nations, only Lesotho, Swaziland, Papua New Guinea, and the U.S. do not require employers to provide paid maternity leave. Another law, the federal Family and Medical Leave Act, ensures that women may take up to 12 weeks of unpaid maternity leave, but sets no standards for compensated time away from work.

By contrast, parents in Sweden get 480 paid days for each of their children. They can also divide up those days between them (for instance, the mother could take 365 days off and the father could take 115 days if they wanted), and can use these days anytime before the child’s eighth birthday. Even Iran offers twelve weeks of paid maternity leave.

While there is no doubt that this sad state of affairs needs revision at the national level, given the effect of maternity leaves on school communities, public school systems should do all they can to improve current policies.

While New York City public school teachers can use their allotted and accumulated sick days to ensure that they receive paid time off for maternity leave, they usually get only 6 weeks. They are also permitted to ‘borrow” up to 20 additional days of paid leave. Once these sick days run out, however, any extra time off is not covered by the NYC Department of Education. Because unused sick days carry over to the next school year, teachers are theoretically able to accumulate a significant number of days. However, doing so can still be a struggle for new teachers or ones who have used their time for other reasons.

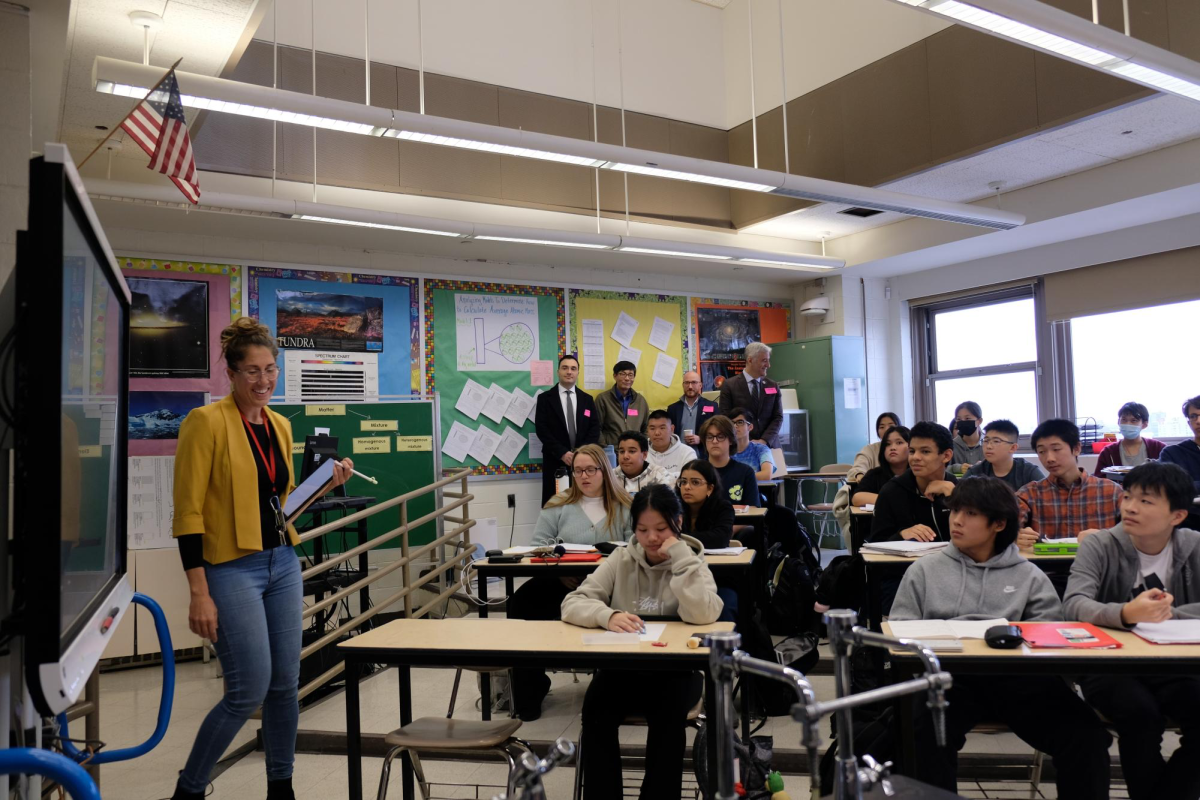

Although Math teacher Sara Liu is expecting a child this summer and will not need to take time off, she believes that current policies still need revisiting. “Six weeks is too short. Women’s bodies often need to recover,” she said.

A similar sentiment was voiced by Social Studies teacher Aliza Sherman. “It can be rough,” she said. “I had three kids within three years, and after the third pregnancy, I had other medical issues that required two more weeks of leave, totaling 8 weeks. I couldn’t walk and I had three babies to take care of. My sister in Israel took a year of maternity leave.”

For teachers, the decision to take a certain amount of time away from work is complex, as it affects not only themselves and their families but their students as well. Often, the substitute teachers who replace them are unfamiliar with their teaching methods, which causes disruptions in the students’ learning and progress with the curriculum.

Earlier this school year, Math teacher Aleeza Widman took off from work to spend time with her newborn daughter.

“It was very different,” explained sophomore Frank Nicolazzi. “The substitute we had was good, but their teaching style was so different from Mrs. Widman, and I feel I understand and do better with her.”

For others, the difference was less pronounced.

“I could still manage to learn since I have other kids in the class to help me. Also, the substitute teacher we recieved offered extra help if we needed. It didn’t affect [my learning] too much when [Mrs. Widman] was gone,” said sophomore Pritchi Banik.

However, juniors and seniors are often more profoundly affected by teachers on maternity leave, as it can be difficult to obtain college recommendation letters from them.

Alumna Cynthia Caceres said, “Students have to ask before they leave, and communication could be difficult … This didn’t happen to me, but I know some who were pressed for time last year [because of a teacher’s absence].”

Other students felt that they should just adjust their own expectations.

“We can’t expect the teacher to leave her baby with someone else just because we think we need her to teach us,” said Rebecca Duras, sophomore.

So what should be done? The answer is simple: offer lengthier leaves of absence for new parents. The problem that parents face: six weeks is too short a time. The problem that students face: six weeks is a long time to be missing a teacher but not long enough for a substitute teacher to establish a sense of continuity. Extending maternity leave solves both; the new parents receive the time they need to spend with their child and the students have a teacher who seems like more than a placeholder.

America likes to claim that it is superior to other nations. As the land of freedom and opportunity, we also like to say that we support families. Why then, are we lagging so far behind on an issue that may be more important to the strength of a family than any other?