Townsend Harris students are taught to become informed and concerned citizens throughout their tenure here. We are supposed to leave this school with the tools and knowledge to make great change in our community and in the world. We are supposed to think broadly and learn how to ask questions and to question authority. All of these ideals seemed to be quickly forgotten in recent weeks when news of potential changes to our bell schedule and a rift in the faculty was leaked to the student body.

Class time became time for teachers to explain to students their side of the story, the injustices brought upon them, and the ways in which the Townsend Harris lifestyle was being threatened. We, as the inquiring student body we are encouraged to be, began to ask around. We talked and rumors began to form, with word spreading that we would have no more clubs or that we’d be in school until 3:30 every single day. After the biased, jumbled, and often inaccurate stories were circulated, students got angry. People tried to start petitions and impact the decisions that were being made.

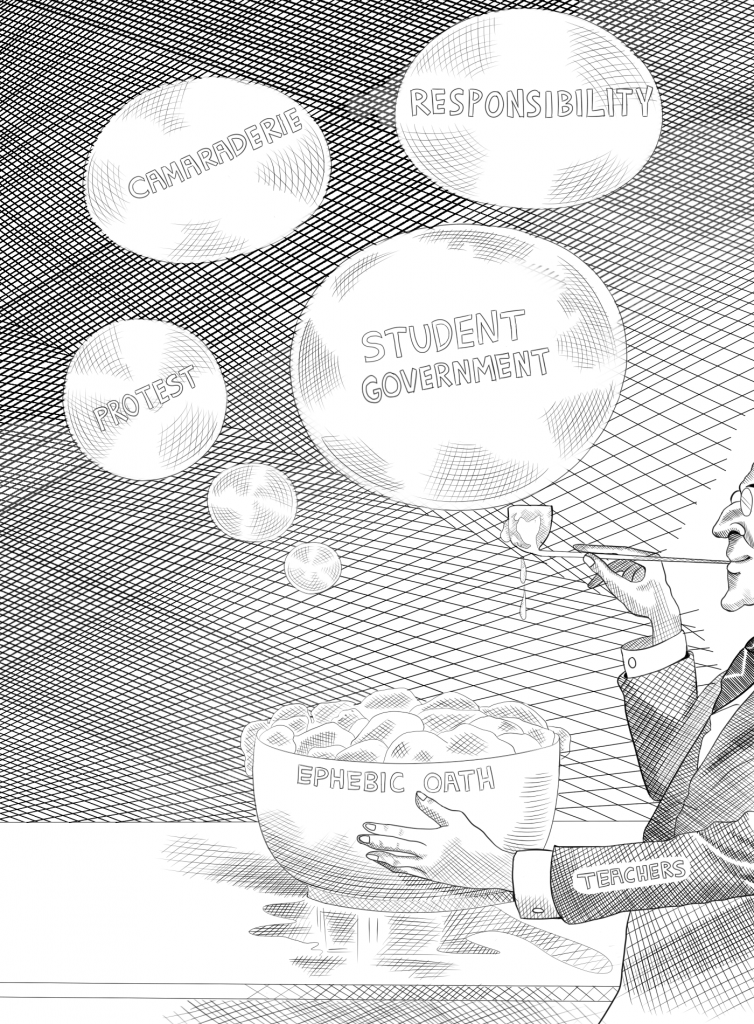

This school teaches that it is not merely our right to take an active role in the shaping of our community, but our responsibility to do so.

We were told to be quiet.

We were told it was not our place to attempt to affect change in the community that affects us most.

We were told to tear our protest posters down.

True, we couldn’t directly affect UFT decisions, but don’t citizens of cities and states and countries have the right to affect the votes and processes of elected officials? Aren’t we supposed to refuse to accept “no” for an answer when those in power tell us to stay away and shut up? The UFT may have the right to do whatever it wants with SBO votes, but knowing how sincerely students would have wanted to be involved in this process, it could have consulted the SU Board in an official capacity. Now members of the SU Board and their constituents rightly feel that the SU is little more than a game of make believe in which students are given the illusion of power and influence.

Why wouldn’t the UFT consult the students if teachers truly believed in teaching us to take part in such processes? Why are teachers probably laughing at the very idea of consulting us?

Some teachers claimed that our brief tenure at Townsend Harris, compared to the years many teachers spend at the school, nullifies our right to join in the process. If anything, the brief time we spend here should give us more of a voice: these are the only four years we spend as high school students, and many of us came here because of the unique schedule and what enrichment had to offer. We deserve a voice, and teachers should be proud rather than angry or offended that we demand one: it is their teaching of the Ephebic philosophy that has inspired us to be so desirous to join in the process of shaping our community. But that pride would be meaningless unless it were backed by actual opportunities for students to voice their concerns.

Many students feel angry and betrayed by this hypocrisy.

What angers us more, however, is that we have been given biased and partial information from teachers. Though many teachers did not devote class time to the schedule drama, we surveyed students during lunch bands and compiled a list of those teachers that did. The list is long and features teachers across departments.

We have to wonder why teachers would choose to confide in us if the dispute was supposed to be kept under lock and key–if it truly was none of our business.

In the wake of these class discussions, many students became defensive and protective of the teachers that they care about. Certain teachers were vilified and singled out as “for” or “against” enrichment. Teachers did not seem to realize that for many students such vitriol between departments does more than rile us up about scheduling issues: it’s hurtful. With the magnitude of interdepartmental tension resulting from this conflict, Townsend Harris ceases to be the inviting and harmonious community it once was.

As the Classic editorial staff, we experienced particular difficulty in trying to accurately report on this issue. When we learned about it, we became eager to roll up our journalistic sleeves, find out the truth and impart it to our fellow students. Many of the same teachers we knew devoted class time to their anger suddenly clammed up when we asked them to go on the record with their opinions. Some turned and fled from us when word spread that we were planning to publish a story on the schedule. Others became incensed that we were daring to write a story before the decision was made final, completely undermining (or willfully ignoring) the job of a newspaper. Is the New York Times only allowed to publish an election article after a president is elected?

Looking over this whole affair, we see one glaring contradiction: teachers made this story our business and then told us it was none of our business. “Don’t worry,” everyone condescended, “It will be fine. Townsend Harris is great no matter what”–as if a name is all that is required to earn greatness.

But if the argument is that we shouldn’t have had a say in this matter because we ‘children’ had to let the ‘adults’ do this important work privately, then perhaps the adults in this situation should have acted less like children. If the input of students would have only made things worse, we have to ask: how could it be worse? The results of the teachers’ efforts are clear: a divided faculty, a crestfallen student body and a schedule that few people in the community believe will make this school “greater than anyone found it.”