“Remote learning has changed my perspective on academic dishonesty and made me more open to the idea of cheating because I’ve realized that a lot of my friends cheat on a regular basis,” said a Townsend Harris student responding to a survey distributed by The Classic in December. It’s hard to say how common this feeling is—only 64 students responded to the anonymous survey, which was sent to over 1,200 students via email—but it seems that students and administrators alike are reassessing what it means to “test” someone’s knowledge.

According to the 2006 book “The Psychology of Academic Cheating,” the majority of students have cheated at some point in their lives, and “cheating is highly influenced by both the demands of the learning situation and the student’s larger social context.”

Today, that larger social context is the age of Zoom. Grids of black squares have seemingly absorbed most of the student population, the side chatter and snide remarks among classmates have been recreated as discrete texts, and the dandy tool of a minimized Zoom window and line of Chrome tabs has enabled multi-tasking. As the classroom went online, testing tagged along. But so did its pressures—and the temptation to turn multitasking into outright cheating.

In the survey that The Classic conducted, 22 students admitted to cheating on an assessment at least once since the start of remote learning. Out of the same pool of respondents, 29 said they’d be more tempted to cheat in an online setting than in an in-person setting, and 33 said they’d be more likely to cheat if overcome by anxiety and had the quick solution of searching the answers online.

In academics, cheating has always been a pervasive issue, and has steadily surged, even before the pandemic. Technology, such as mobile devices and internet connection, have become more readily accessible, while increasingly more competitive college admissions linger in the minds of students seeking to secure a higher education.

However, some assert that technology is not the culprit in the long-standing cheating situation in academia. “Ever since the first monks were saying, ‘Oh, those new styluses are allowing them to illuminate those manuscripts much more easily, that’s clearly dishonest,’ there’s been somebody who thought the new technology makes [cheating] so much easier,” said David Rettinger, a professor of Psychological Science at the University of Washington Mary, in a Wiley webcast past July (qtd. in Inside Higher Ed). “The reality is that there has always been people using technology for good and for ill. I don’t think the internet is an epochal technological change—it’s just another in a series of the wheel turning.”

If technology isn’t what’s making us cheat, then what is?

While most of those asked in the survey said they’d feel guilty about cheating, 15 people said that there are certain circumstances that absolve them from their guilt. As THHS principal Brian Condon put it, motivations and justifications for cheating can be deconstructed into two main parts: the institutional and personal side.

From the personal side, Principal Condon maintained that a person may be impelled to structure an ethical system grounded on consequentialism, essentially that the ends justify the means. One survey respondent said that they believe the curriculum is much too restrictive and that a numerical grading system is an inadequate measure when applied to a person’s potential, thereby making cheating permissible to attain something greater: the goal of higher education, “something that we consider integral in life, the right college.” Other responses to the question “Do you feel guilty about cheating?” varied from “No, as long as I don’t get caught” to “No, as long as everyone else is doing it” and “No, as long as I get a good grade.”

On the institutional side, two factors might be involved in kindling the urge to cheat: either the testing system or teaching methods. The Regents, for example, don’t give any constructive feedback, making the student rely solely on the resulting score and dwell on the numerical value for a sense of their own intelligence, Mr. Condon said. In a classroom setting, he continued, if testing results are deficient across the board, it may prompt the need of a change in how the tested material is taught.

Problems with these assessments predate remote learning. In April of 2019, THHS Physics teachers had departed for a robotics trip, leaving behind a unit exam for the regents students to complete and a substitute teacher to proctor. The students from bands 3 to 9 disseminated pictures of the exam amongst themselves.

“The temptation to cheat primarily arises from the desire to earn a good grade but without the typical effort required to earn it when a student is unsure of their own proficiency in the material,” said Physics teacher Joshua Raghunath, one of the teachers who left on the trip. “Statistically students that are confident in their ability to digest the content in a course see no benefit in cheating when the risk is getting caught for academic dishonesty.”

“I think if we learned anything from the scandal it’s that students will find ways to cheat regardless, be that by finding answers online or even going so far as to steal the test and distributing it to their classmates” said senior Karen Lozano. “Even now where some classes make you record yourself as you take the test, people find ways in which they can cheat.”

Meanwhile, according to an anonymous student, mistrust in student academic honesty was not willed out of a vacuum during remote learning. In one of her math classes last year, the student said, the teacher was intent on having the class put down their pencils once the test had ended, otherwise ten points would be deducted at the sight of a moving pencil after time was over. Though not necessarily opposed to the rule, the student said it would sometimes prove to be too extreme, such as when forgetting to write down your name on a test, it would risk losing test points while discreetly scribbling it in. “I would hesitate to even the simplest of actions like look at the clock or the board,” the student said.

Some students rationalize academic dishonesty by putting the blame on teachers, such as the student who responded to the survey by saying cheating was justifiable if the teacher did not “do enough” or “care enough” to make them feel well equipped for the exam: the “cheat or be cheated” justification.

Survey respondents who condemned cheating largely said they feel as though cheating compromises the integrity of an assessment, is unfair to those who didn’t cheat, and is unethical.

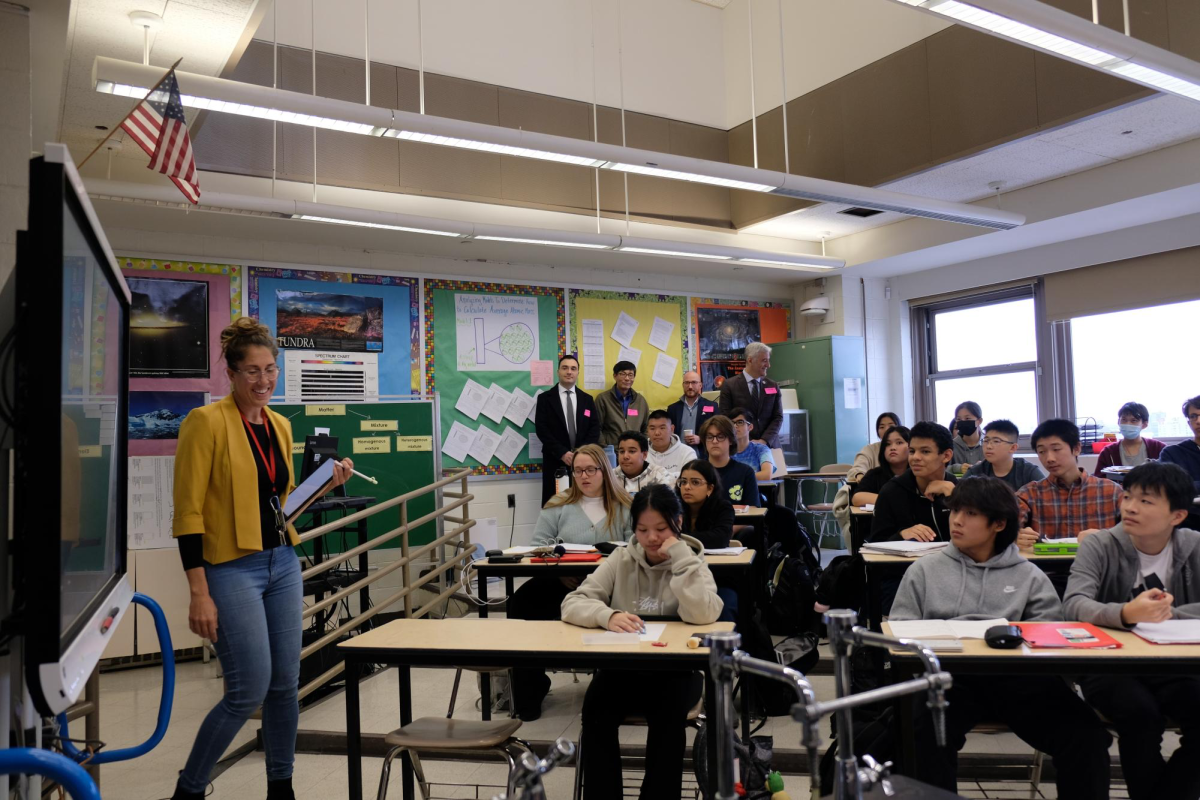

“When you select for people who are highly motivated by grades on exams and tests [through THHS admissions], and see their value in that, you have to be extra judicious about how you set up your assessment system,” Mr. Condon said. “And I think this is where the school has needed to improve and that was something I noticed almost immediately when I arrived.”

With distanced learning, the ability that teachers possess to monitor cheating has depleted drastically. “It is probably easier to cheat in a remote setting than in person situations since [in the latter] the teacher can actually monitor the students better and put in some measures that deter cheating such as separate the tables or put a physical barrier between students,” said Shi Bing Shen, AP Psychology teacher. “I have used the AP Classroom lockdown feature to try to reduce cheating; however, I do believe more cheating is still going on this year than in-person years.”

To compensate for the lack of proctoring capacity, one anonymous student said that in her math class, the teacher instructs students to tilt their webcams towards their test paper in such a way that the content of the assessment and student’s work cannot be seen to ensure they aren’t trying anything suspicious.

One student said that in one of her science classes, testing is sometimes done through AP Classroom, which gives teachers the ability to know when students are on another tab that is not the test. The student said that she discovered the teacher had this ability when some students went off the testing tab and were then shortly warned by the teacher. Though she doesn’t mind this sort of preventative cheating measure, she said she is concerned the CollegeBoard implements this without notifying students of this feature.

Though believing these rules inhibit cheating, another student said they feel that their “every move is being watched by the teacher,” and has forced them to become more conscientious of their actions during a test, even inducing a hesitancy to do certain actions with the concern that it may be perceived as suspicious and potential cheating behavior, regarding measures of the like from above.

Dr. Douglas Harrison, the Vice President and Dean at the School of Cybersecurity and Information Technology at the University of Maryland, Global Campus, contends that instead of pushing for exams that are more cheat-proof, assessments should be designed to be more meaningful and authentic. Harrison spearheads the university’s initiative in strengthening online testing security. Putting the entire blame upon the students, Harrison argues, “runs counter to research” and “risks stigmatizing all students as cheaters,” shifting the “pedagogical focus away from developmental teaching and learning and toward a fixation on punitive measures, and wastes an opportunity for a more reflective approach to online assignment and assessment design.”

So why do we cling on to traditional testing if its integrity can no longer be secured?

Some educators, like AP World History teacher Aliza Sherman, have opted for alternative forms of testing. Mrs. Sherman now assesses her students with seminars rather than traditional exams. “I need to explore the options that are available in terms of testing and consider which would be the best suited for this unique situation” during the pandemic, Mrs. Sherman said.

However, such adaptations lend easier to certain subjects than others. “STEM courses usually have a definitive answer to the problems posed. A seminar would be unfit for these classes because open-ended questions are not really an option, since there is only one single answer,” junior Michelle Wu said. Due to the nature of the assessments, Michelle said it is harder to stray from traditional testing, thereby making STEM exams more susceptible to cheating. Among the survey’s 64 respondents, students were more inclined to cheat in STEM classes. Twenty-one students said they are most disposed to cheating in science, with math being a close runner up at 18 votes.

“For math and science, I think it should be required for the steps to be shown because if the students don’t know how to do something and they search the questions online, the steps are sometimes shortened or skipped,” junior Sky Jiang said.

In response, some STEM teachers added tools to their testing methods during the pandemic.“Remote learning has changed how we administer tests as faculty need a way to collect student work and responses in an efficient manner,” Mr. R said. Citing the 2019 physics cheating incident, he said a solution is to “limit the opportunities that students have to share information amongst themselves.” This includes having all classes taking summative assessments simultaneously, making versions of the exam with different questions, and using projects as the assessment instead.

Others have restructured their grading policies to add more weight on alternative testing modalities, such as projects. “For this year, I have given equal weight to my tests and projects,” Ms. Shen said. “I still have to give my students the traditional testing format since this is how they will be tested on their AP exams.”

“Instead of assigning traditional exams, I think that math and science courses should offer more projects,” Michelle, one of Ms. Shen’s students, said. “In my AP Psychology class, Ms. Shen weighs and considers projects more than exams, taking into account presentation and content. Not only will projects allow students to collaborate with one another, but it will also allow teachers to see other aspects of the student’s personality when he or she is presenting, one being his or her creativity.”

To get a sense of students’ ideal remote learning science class, Mr. Raghunath gave his classes the optional opportunity to write a paper that delineates the student’s preferred method of instruction and class setting. From the responses, he said the results were conflicting.

“From a recent extra credit assignment given in my classes students have stated that discussion during the class is one of the most helpful activities for them in learning the material. Not only teacher-student discussions but also student-student discussions,” he said. “Yet this is exactly the opposite behavior that the students exhibit in class as most students are extremely reluctant to speak at all. When it comes time for assessments however the students seek to have group assignments rather than complete assessments individually.”

Similarly, some students find testing at times to be problematic and counter-constructive. According to interviewed students that asked to remain anonymous, the classes wherein stringent testing protocol is in place to reduce cheating attempts, whether in remote learning or not, can make it more difficult for them to test.

“I feel that working to discourage cheating in a remote setting can unintentionally encourage students to find ways around it. Students can stick something onto the side of their screen or above where they are working, so tilting their webcams down doesn’t help facilitate a better testing environment and if anything, inconveniences the student,” said one student.

For next steps, Mr. Raghunath said, “Moving forward both faculty and students need to understand that remote learning requires both parties to buy into the system for it to prove successful. Teachers need to become fluent in platforms that will improve their pedagogy and students need to embrace the remote learning environment fully in order for it to be effective.”

“Treating tests like they are somewhat open book while having some sort of time limit (within the band) can encourage students to be prepared without adding stressors to an already awkward situation,” a student proposed.

“While I can see why current circumstances might make people more open to cheating, I believe that remote learning has made it so that I and others can focus more on ourselves rather than what our peers are doing. I know that my teachers are doing their best to support and prepare me during these difficult times and I’m very grateful for that,” said one student.

Harrison wrote that “under the current circumstances, there will be realistic limits to how much anyone can use the move online to introduce more authentic assessment. That’s OK.” He said that no matter what an individual teacher’s approach to online teaching and testing, there’s one lesson that’s most important to take away from this moment: The “adaptability and resilience” that is at the crux of a “commitment to lifelong learning.”