The first known case of COVID-19 was discovered in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. Since then, the virus has spread globally, inflicting approximately 117 million cases worldwide. Now over a year later, the virus continues to infect tens of thousands nationally..

As cases grew, variants have also emerged. SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, is part of a group of coronaviruses. Not all coronaviruses infect humans – some also infect animals. In fact, SARS-CoV-2 is one of seven coronaviruses that can infect humans. Mutations, or changes in a virus, can occur when viruses get copied incorrectly. According to WebMD, “when viruses infect you, they attach to your cells, get inside them, and make copies of their RNA, which helps them spread. If there’s a copying mistake, the RNA gets changed.” This process creates new variants of the virus.

Although the terms ‘strain’ and ‘variant’ are often used interchangeably, according to CTV News, they aren’t the same. A new strain is only developed when the virus has gone through enough mutations. If there are only “minor accumulations of mutations,” then it’s considered a variant, not a strain. SARS-CoV-2 itself is “a strain of β-coronavirus (CoV).” Currently, according to David Robertson, head of Viral Genomics and Bioinformatics at the Centre for Virus Research, experts don’t have enough research to definitively conclude that there is more than one strain of the virus.

Fortunately, according to the Treatment Action Group, and a research paper written by doctors Adam Lauring and Emma Hodcroft, SARS-CoV-2 mutates relatively slowly compared to other RNA viruses due to an error-checking mechanism pertinent to coronaviruses. While there are numerous variants of SARS-CoV-2, most mutations aren’t significant enough to garner interest. However, as the CDC suggests, some variants are quite notable such as B.1.1.7 (UK), B.1.351 (South Africa), and P.1 (Brazil). Here is an overview of these three variants:

B.1.1.7.

Mutations

This variant has a total of 23 mutations. Notably, one mutation, named N501Y, affects the virus’ “entry into human cells.” Additional mutations of this variant include P681H and the 69/70 deletion whose effects aren’t completely known according to the American society for Microbiology. However, some researchers and scientists have suggested that this deletion, along with the N501Y mutation, can possibly make this variant of the virus more transmissible.. These three mutations are “hypothesized to have the largest potential biological effect.”

Further research and studies on the B.1.1.7 variant need to be conducted before definitive statements are made regarding its transmissibility. However, currently, it appears as if this variant has an increased infectivity, but Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, claimed its impact on the human body is generally the same as the original virus. In January, 2021, some UK scientists speculated that “the B.1.1.7 variant may be associated with an increased risk of death compared with other variants.” However, this is only one study and the CDC suggests that in order to reach a definitive conclusion, more studies will need to be conducted. The vaccine is still shown to be effective against this variant according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Origin

The first two cases of B.1.1.7 were detected in the UK. They were found on September 20, 2020 and September 21, 2020 respectively. This variant of the virus continued to spread throughout the UK in December. In mid-December, 555 sampled genomes of the variant were found in Kent, 519 were found in Greater London, and 545 were found in other UK regions as well as a few other countries outside of the UK.

Cases

The variant was first found in the UK around September of 2020. Since then, it has spread to France and Spain as well as over 68 other countries, including the U.S. In fact, in the U.S., over 600 cases of this variant have been reported as of mid-February, with this amount “doubling every ten days,” reported Dr. Mira Irons, Chief Health and Science Officer at the American Medical Association (AMA). It may soon become the most prevalent variant of the virus in the U.S. Indeed, as of mid-March, over 3,700 cases of this variant have been reported in the U.S.

B.1.351

Mutations

The B.1.351 variant is ostensibly around “50% more transmissible than” the origin virus strain. Even worse, there is evidence that various COVID-19 vaccines are rendered less effective against this variant. For instance, the Johnson & Johnson vaccine is reportedly “72% effective in the U.S.,” but “only 57% effective in South Africa,” where the majority of COVID-19 cases are caused by the B.1.351 variant, the most dominant SARS-CoV-2 strain there. Similarly, while the Novavax vaccine is about 85% effective with the B.1.1.7 variant, it is “only 50% effective” with the B.1.351 variant.

In addition, antibody production is lowered with B.1.351 by six-fold compared to the other variants in patients vaccinated with the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine. This means that immunity against the virus after getting the vaccine is lower against B.1.351 compared to the immunity level after getting the vaccine against the original strain of the virus. This also applies to people who have gotten COVID-19 before: 90% of a group of “44 people in South Africa” have been shown to have “reduced immunity against the [B.1.351] variant,” and around half of them even “had no protection against it” at all. However, some protection is still offered by these vaccines, and Moderna is working on making a third vaccine dose in addition to the two pre-existing ones in order to offer more protection against the B.1.351 variant.

Junior Daniel Song expressed his concerns regarding this and said, “I think soon the COVID variants will pose a greater challenge to the vaccine, and life will have to become restricted once again before the vaccines are modified to combat the variants.” By contrast, freshman Andrew Li said he feels that these new variants won’t cause a huge surge in cases as long as people still continue to be cautious. However, he feels that people won’t take the recommended precautionary measures, which might lead to “a second rise in cases.”

Origin

The first detected case of this variant was found in Nelson Mandela Bay, South Africa in the first half of October 2020. By the second half of December 2020, this variant was also detected in Zambia where “it [already] appeared to be the predominant variant in the country.”

Cases

Currently, over 13 countries have reported cases of the B.1.351 variant, including the UK, The Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Australia, and Iceland. “At the end of January 2021,” this variant spread to the U.S. As of mid-February, there were only 9 reported cases of this variant in the U.S. Presently, there are 108 reported cases of the B.1.351 variant in the U.S. but only 1 in New York.

P.1

Mutations

The P.1 variant possesses 17 unique mutations. Although nothing is definite as of mid-February, there is a possibility that antibodies might not be as effective against this variant. There may also be an increase in transmissibility of this variant as shown through a study in Manaus which revealed that despite 75% of the people there having contracted SARS-CoV-2 prior, there is still “a surge in cases,” which could be due to this new variant reinfecting people.

Origin & Cases

This variant was found in four Brazilian travelers heading to Tokyo, Japan. These travelers were in Haneda airport when they got tested for the virus. The virus later spread to a total of 15 countries including Brazil, South Korea, and Germany. The virus eventually spread to the U.S. in late January of 2021, with Minnesota and Oklahoma being the first U.S. states to report cases of this variant.

What does this all mean?

According to an article written by The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, it’s normal for viruses to mutate. RNA viruses, like SARS-CoV-2, mutate more frequently than DNA viruses due to less stability. DNA viruses contain “a proofreading check” that prevents as many mistakes from occurring during DNA replication, leading to less mutations. Oftentimes, these viruses mutate in order to “enhance virulence and evolvability.” The mutation rate of SARS-Co-V-2 is fortunately controlled “due to an exonuclease” that checks for replication errors. Many times, various mutations aren’t harmful, but a few do end up being more potent than the original virus.

This is where the need for increased SARS-CoV-2 surveillance comes in. Monitoring the virus can help with identifying and controlling future variants. Sophomore Alex Cho said he feels that “with the vaccines having been produced and distributed…it wouldn’t be too long until the pandemic will end.” However, he also said that he does think that returning completely back into our pre-pandemic life might “take a while” due to continued caution among people. Andrew also agreed, and said that he thinks that even with the vaccine, there could be long-term effects in the sense that people might still be cautious when going outdoors even after the pandemic ends.

Indeed, the CDC, Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention, still recommends that people take precautionary measures, like social distancing, wearing masks, and limiting large gatherings, even if they’ve already gotten vaccinated in order to prevent the spread of the virus. If everyone takes extra care in following these precautionary measures, then we can prevent further spread of the virus.

Many Harrisites expressed their wishes to return to pre-pandemic life. Junior Brian Lin misses his PSAL team’s practices and outdoor events. “I just miss being able to go outside and enjoy the air and sun. I can’t remember the last time I went out and took a stroll,” he said.

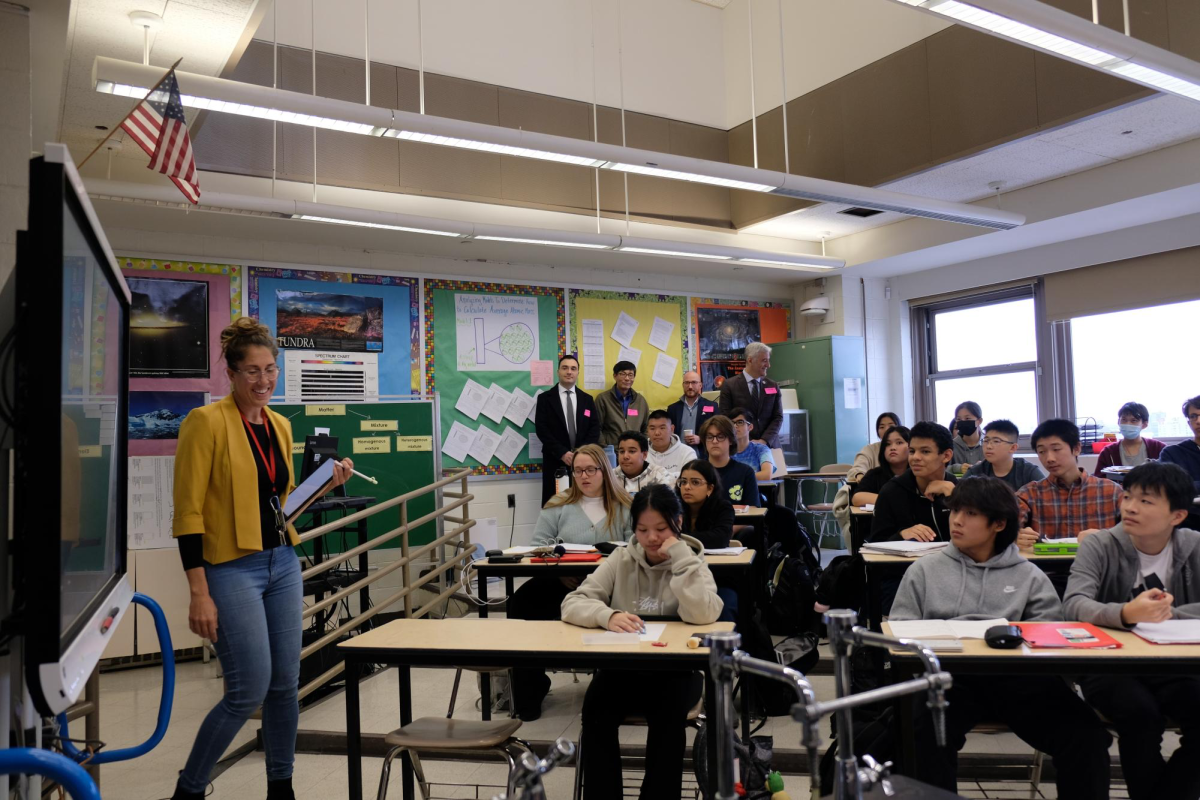

Alex similarly misses in-person school activities like S!NG and FON. “I personally want the pandemic to end since I want to go back to the time when I was able to meet my friends without worrying about getting sick, and going back into the school environment to interact with other students. Things just aren’t the same without virtual classrooms and empty streets,” he said.

March 11 marked the one-year anniversary since the World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared the COVID-19 pandemic. March 15 marked the one year anniversary of quarantine. More than 119 million cases of the virus have been detected worldwide. Fortunately, approximately 67.3 million of these cases led to recovery. However, there were also more than 2.62 million deaths globally. As the pandemic progressed, more and more regulations and restrictions were put into place, temporarily shutting down tens of thousands of restaurants, salons, barber shops, and countless stores. People and families began to run into financial issues due to unemployment, and schools transitioned to remote learning.

With several vaccines now available, we may be closer to reaching our new normal. Until then, safety guidelines will continue to be put in place to limit the extent of the virus’s spread.