Now over one year since the COVID-19 lockdown began, much has certainly changed. Looking back on a year of change for Townsend Harris students, we can’t help but think of the losses so many have suffered, while still recognizing the resilience and hope out there. It feels like a lifetime since our in-person Festival of Nations, a celebration of the diversity in the THHS community that is a highlight of the year for many students. Last year’s event served as one of the last times students, faculty, and families joined together before the shutdown.

As FON aims to celebrate many of the cultures represented within the THHS student body, now is a time to also reflect on how we all also come from different parts of New York City.

Though The Classic usually tells the stories of what occurs within the halls of Townsend Harris, those halls have expanded well beyond Melbourne Avenue in the past year as our city became the epicenter of this global pandemic. And so, we are beginning a series of articles meant to highlight the various pockets of the city that our student body has taken refuge in since March 2020. Our first story is about Forest Hills, and how a graduate of Townsend Harris worked with a number of friends to help preserve the once thriving food culture at the heart of the community.

Elmhurst Hospital: where does it stand now after the peak?

By Daniela Zavlun, Nataniela Zavlun, News Editors

Overcrowded emergency rooms, doctors in hazmat suits, the hum of ventilators. Lines of people waited outside the hospital as ambulances blared through the streets and reporters frantically tried to catch a glimpse, while inside doctors and nurses scrambled to meet the rising demand for treatment. In spite of all this, 13 patients died on March 24, 2020.

When COVID-19 struck New York in March, Elmhurst Hospital in Queens quickly became ground zero for the virus, garnering national media attention as the center of an unprecedented health crisis. During those first few weeks, Elmhurst seemed on the brink.

Today, there are no lines or steady streams of ambulances.

What happened shows how the hospital adapted to an unprecedented health crisis, while still failing to address some of the larger structural issues that plague the New York healthcare system.

Elmhurst Hospital is one of 11 public hospitals in the New York healthcare system, which also includes private hospitals that serve low-income communities and five networks of large, well-funded private hospitals. These private hospitals typically have the largest number of well-resourced beds, billion-dollar reserves, and are the most financially connected. Hospitals like Elmhurst, on the other hand, are often under-resourced and do not have the funds to pay hospital workers as much as a private hospital could—despite treating the most vulnerable populations in New York.

Even prior to the pandemic, the Elmhurst neighborhood was a well-built fireplace waiting to be lit—and COVID-19 proved to be a potent match, illuminating many pre-existing conditions that allowed the virus to concentrate there in the first place. Much of this has to do with the composition of the Elmhurst community itself, which primarily consists of low-income, immigrant families.

In 2018, a survey done by the NYU Furman Center found that Elmhurst’s median household income was $54,250, 16 percent less than the citywide household income, and its homeownership rate was 24 percent, while the citywide homeownership rate was 32.8 percent. An Elmhurst doctor writing in The New York Times reported that one in five people living in Corona and Elmhurst live in poverty. This means that most of the population occupies low-income jobs that don’t allow them to work from home. They can only afford to take public transportation to and from those jobs, forcing them to routinely expose themselves to the virus. Elmhurst also has one of the highest rates of severely crowded housing in the city, making it more difficult for residents to follow quarantine lockdown measures and practice social distancing.

Angela Trozzi, a clinical dietitian at Junction Boulevard Health Center (a health center near Elmhurst), witnessed the overcrowding of patients in that area when the pandemic hit. “I think it was such an issue in this area because I work closely with a social worker and she says that whenever she interviews patients there are so many people living in these small apartments. These are multigenerational homes so it ranges from young kids to older adults and that’s probably why it concentrated pretty badly in Elmhurst,” she said. “That and I think a lot of people use transportation because not a lot of people have their own cars, but I think the small living quarters was definitely the main thing.”

With limited public hospital options nearby, low-income, uninsured, or undocumented patients that don’t have access to private healthcare crowd the emergency room of Elmhurst Hospital.

Public hospitals like Elmhurst do not consider a patient’s ability to pay when providing treatment. As a result, they often shoulder the burden of caring for low-income patients in the neighborhood.

In a Wall Street Journal podcast, internist Bob Thomas explained that he came to work at Elmhurst for precisely that reason. “I wanted to take care of people who didn’t have access to care, so when I came here to this hospital, I was amazed by the NYC model in which there are these city hospitals that would take care of everyone,” he said. “In this community, there are people who came from countries where they didn’t have access to healthcare. I always thought in places like Mount Sinai, there could be great doctors and if I weren’t there, then there would be other great doctors. But in places like Elmhurst, if it weren’t for Elmhurst [Hospital] these people would have no place to go.”

The Junction Boulevard Health Center is one of the few other public healthcare institutions that accept patients regardless of access to healthcare. In severe cases, they would advise patients to seek treatment at nearby hospitals, like Elmhurst Hospital. Still, many avoided doing so out of fear that they could contract the virus from others or that hospitals wouldn’t have enough space to treat them. Ms. Trozzi said, “If you call the hospital, they were sending you home unless you were like, dying dying. So I think they were scared they wouldn’t have enough space…Our hospitals do not have the capacity to treat as many people as we need them to.”

New York also does not have a collaborative healthcare system. Hospitals run independently and seldom communicate with one another, seemingly driven by economic competition. A New York Times article found that private New York hospitals “invest heavily in their brands,” spending a collective $149 million on advertising. When the coronavirus crisis hit in March 2020, there was no communication system to match patients to empty beds. While the Elmhurst emergency room overflowed with patients, nearby hospitals still had available beds.

The gulf between private and public hospitals became even more evident as the pandemic progressed.

While the five most expensive private NYC hospital networks were earning more than they spent, public hospitals like Elmhurst already had billion dollar deficits. This gap grew even larger because while all hospitals were facing revenue loss as a result of canceled expensive surgeries and procedures, only private hospitals could afford to stomach these dramatic losses.

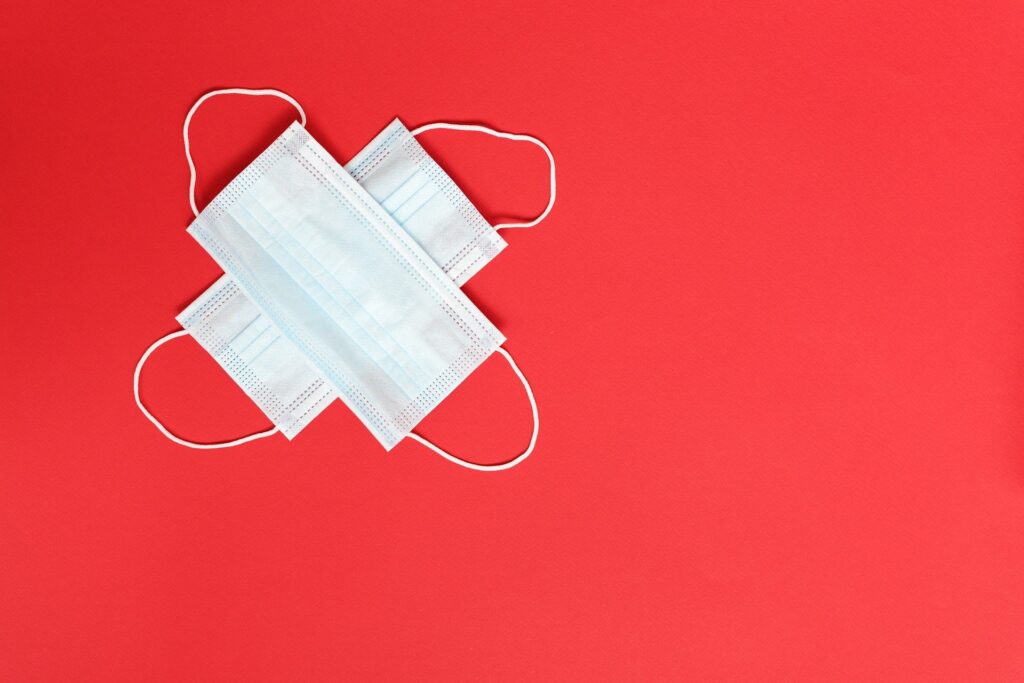

Lacking the resources of a private hospital, Elmhurst staff faced a shortage of supplies and PPE as emergency rooms became increasingly packed.

Gulnara Sipetic, a nurse at Elmhurst Hospital, said, “At the very beginning we had this really big shortage so people would put whatever they could on their faces, like those shields… mostly gown and gloves were required, the rest was up to you because the rest was hard to get….there also weren’t enough respiratory therapists.”

In the following weeks, the ongoing crisis forced Elmhurst Hospital and the New York public healthcare system to address these issues. The state created a live daily map of conditions at each hospital to make patient transportation more efficient. The Health Affairs journal reported that they also developed an electronic system for sharing information about technological advances and bed availability across hospitals. This advancement “bridged divides between different hospital systems across New York City to encourage the sharing of data and improve patient care” and prepared all NYC hospitals, both public and private, to “work in a more integrated fashion in the future.”

Elmhurst also quickly received an influx of additional personnel. “We had an entry unit where military doctors would work…help came from all over,” said Ms. Sipetic. “We got hit the most, but I think we also got the most help.”

By the fall, Elmhurst was better prepared to handle the oncoming second wave. With the improved organization of the NY healthcare system, the hospital had more room to treat both COVID and non-COVID patients and was able to more effectively separate them. T.E.R., a former employee and patient that tested negative for COVID -19 at Elmhurst Hospital in November, said, “The rest of the unit patients had plenty of room to be treated individually or in pairs.”

Still, as case numbers started to drop in the warmer months, they began to lose some of this extra staff. “All the extra help we hired, the nurses, they were finishing their contracts [as COVID cases were going down] and they didn’t want to go back because they were making money…they were gone towards the end of June,” Ms. Sipetic said.

Newly distributed COVID -19 vaccines changed this landscape. AMNY reported that Elmhurst Hospital became the first hospital to receive COVID -19 vaccinations for its staff in December. Thus, fewer hospital personnel took leaves of absence due to infection in this second coronavirus wave, leaving more available to tend to patients than in the spring and offsetting the cost of another round of additional hires. Hospitalizations due to COVID-19 have also decreased as a result of vaccine distribution efforts.

Elmhurst and neighboring health centers like Junction Boulevard have also started offering significantly more telehealth visits, which reduces crowding within hospitals and the use of public transportation while allowing health professionals to see more patients daily. “I think in general we were spreading appointments out a lot but we don’t have to do that anymore because of the telehealth visits and now I have way less no-shows,” said Ms. Trozzi. “Elmhurst definitely pushed other hospitals to roll this out faster because you can reach so many more people this way.”

While much has improved, many issues predating the virus remain. Many Elmhurst residents still work minimum wage jobs and cannot afford days off (even due to illness) due to extensive small business closures and a wave of lay-offs. The flight of more affluent New Yorkers has not relieved overcrowded housing, as much of the Elmhurst population is low-income and therefore not financially stable enough to relocate amidst a pandemic.

However, in bearing the brunt of unprecedented circumstances, Elmhurst has set an example for other hospitals that will have a lasting impact on the NY healthcare system long after COVID-19 is no longer a threat.