Last month, after a sixth alumna spoke to The Classic to share allegations of educator sexual misconduct, the former editors-in-chief published an editorial calling for Townsend Harris to have direct training on educator sexual misconduct. In the piece, the editors promised that The Classic would follow up with a feature that explores what constitutes effective training related to educator misconduct and Title IX, the civil rights law that protects students from various forms of harassment and misconduct. This is the feature The Classic pledged to write.

“I was groomed by a predator at the school for over two years,” a 2013 alumna wrote in an email to The Classic. “I had to undergo around six years of therapy to come to terms with it and move on in life. I haven’t yet felt like I’ve fully recovered from that nightmare.” She reached out to The Classic after reading an article from May 2020 on allegations of educator sexual misconduct at THHS. The teacher accused by this alumna—along with the two additional teachers accused by five other alumni detailed in the 2020 article—do not currently work at the school. The Classic cannot confirm that these accusations are connected to why the teachers no longer work at the school. While the alumni who spoke to The Classic about these experiences have graduated, the current student body appears to still lack essential information on how to protect themselves from educator misconduct.

Between May and June, 82 students responded to a survey from The Classic sent to over 150 students about educator sexual misconduct. The survey was not scientific and participation was voluntary and anonymous; however, the responses provide important insights. In particular, 61 of the 82 students said that they do not know who they should speak to if they need to report educator misconduct, and 47 students said that they cannot identify the type of grooming behaviors that the alumna who spoke to The Classic said she experienced. Moreover, many of those who claimed to be able to identify grooming behaviors did so incorrectly when asked to offer examples.

Child grooming is the process of gradually coercing a minor into sexual activity. Through manipulative tactics, perpetrators cultivate trust with their targets until they are more likely to be victimized. For educators, grooming behaviors can include frequent texting and social media contact, rides to and from school, gift giving, and more. Some of these behaviors might be appropriate depending on context, which can make identifying grooming behaviors difficult.

Of the 35 THHS students who claimed they could identify grooming behaviors, 11 identified acts that go beyond grooming and would need to be reported immediately should they occur. For instance, one student described “doing sexually explicit stuff with students” as grooming behavior. Another student included “caressing in inappropriate places” in their list. Multiple other students also referred to inappropriate touching of the student’s body as a grooming behavior.

These responses suggest that the THHS student body needs more in-depth training on this topic. While freshmen, sophomores, and juniors attended a Title IX workshop in April, three junior attendees reported that educator misconduct was not part of the presentation, which focused on student-to-student misconduct.

To understand the necessity of specific training on educator misconduct, The Classic consulted Dr. Charol Shakeshaft, a leading researcher at Virginia Commonwealth University who specializes in studying educator misconduct.

Dr. Shakeshaft said that while the DOE has policies in place to address educator misconduct, there’s a difference between having policies and ensuring students understand them and are trained to identify and respond to difficult situations.

“What school districts will say is that we have policies, people can look them up on the website. They can look at our school policies, they can see what the policies are, and that’s true,” Dr. Shakeshaft said. “But if the school district wants to, especially if the school district has had reports of violations of those policies, it’s a really good idea for that school district to say to its constituency, meaning students, parents, and staff just a reminder, these are our official policies, that’s what this means, this is what we do, this is how we train, and this is what we expect you to do if you see anyone violating these policies.”

The Classic also reached out to sexual misconduct prevention organizations such as Stop Sexual Assault in Schools (SSAIS). In an email, Dr. Esther Warkov, Co-Founder of SSAIS, said, “Research has shown that sustained campaigns are far more effective than just classroom lessons.”

Dr. Shakeshaft described what educator misconduct training should encompass. “The training for students is about what the boundaries are and when the teacher crosses or a school employee crosses that boundary, what the student is supposed to do, what they’re supposed to report, how they’re supposed to report, and why they’re supposed to report,” she said.

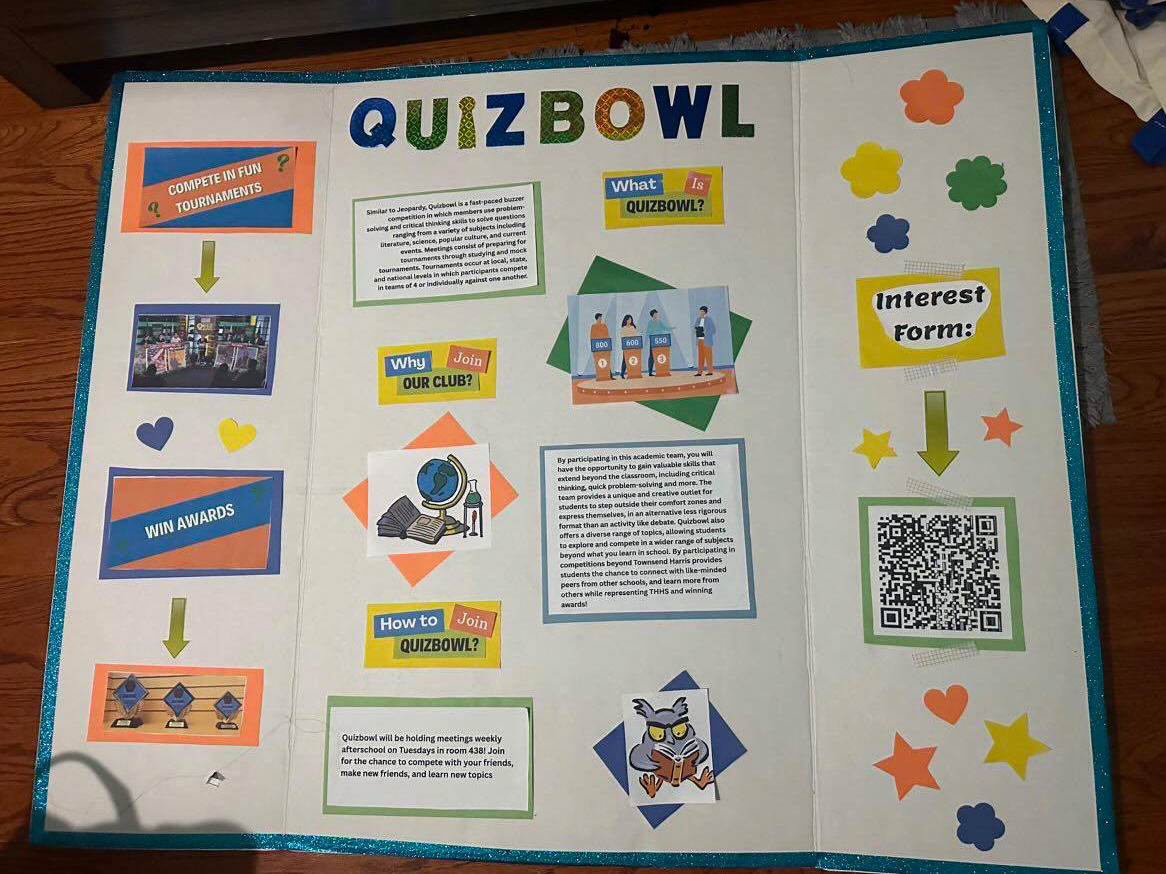

In the summer of 2016, The National Association of Independent Schools (NAIS) and The Association of Boarding Schools (TABS) created the Independent School Task Force on Educator Sexual Misconduct. The Task Force released a report in 2018; part of the document provides recommendations on how schools can create effective training on the topic.

“The education of young people is based implicitly on trust. Embedded in that principle is the fundamental expectation that schools will provide a safe environment for students. Educator sexual misconduct undermines bedrock expectations and the central purpose of schools,” the document reads.

In March 2017, the US Department of Education released a similar report, called “A Training Guide for Administrators and Educators on Addressing Adult Sexual Misconduct in the School Setting.”

Between both reports, common recommendations for training programs include the following:

- Students should learn a clear definition of adult sexual misconduct (ASM) and recognize common behaviors of ASM perpetrators

- Students should know when, how, and why to report both ASM they experience and suspicions of misconduct they witness as bystanders

- Students should be able to define grooming and identify signs, both through electronic and in-person exchanges

- Schools should craft an age-appropriate description of the school district’s policies in a way that clearly conveys and clarifies the rules and procedures through specific examples

- Schools should hold respectful discussions explaining the characteristics of students who are at risk for being targeted by ASM perpetrators

- Schools should train students to understand any rights to anonymity and privacy that they are entitled to (or not entitled to) when reporting an incident

- Students should learn what qualifies as retaliation and understand their rights to not be retaliated against for filing reports

Multiple experts recommend that this training should be yearly for both students and for all adults working in the school. Experts also say that parents should receive or at least be offered similar training.

“I think it is better to be proactive especially if there have been allegations and reports than to be quiet. Because silence often is translated into agreement, or denial,” Dr. Shakeshaft said.

As the new editors-in-chief, we can commit that The Classic will continue its coverage on the training necessary for fostering a comprehensive environment that can prevent educator misconduct. This article focuses on student training. In the fall, we will return to this topic, report on what training for adults should look like, and seek perspectives from the THHS administration on these expert recommendations.