Starting this June, teachers will no longer grade their own school’s Regents exams. Instead, teachers will grade other schools’ exams at off-site regional facilities or on computers, in an effort to prevent cheating.

In September 2011, the Board of Regents investigated a 62-page database of cheating allegations. It found that schools often gave more lenient Regents grades than groups of expert scorers, allowing several students to pass with the minimum grade. Since standardized test scores have become detrimental to a school’s survival, some teachers have inflated students’ grades to improve their school’s reputation.

Science teacher Phillip Porzio sees the ban as a sign of distrust from the Department of Education.

“We all have a moral obligation to grade correctly and maintain the integrity of our job,” he said.

However, he also thinks that it will be effective because teachers “won’t remotely know who they’re grading.”

Although science teacher Katherine Cooper says she can’t have a final opinion on the policy until the results are seen, she feels that teachers who abide by the rules are being unfairly punished.

“To call into question everyone’s profession is disheartening,” she said.

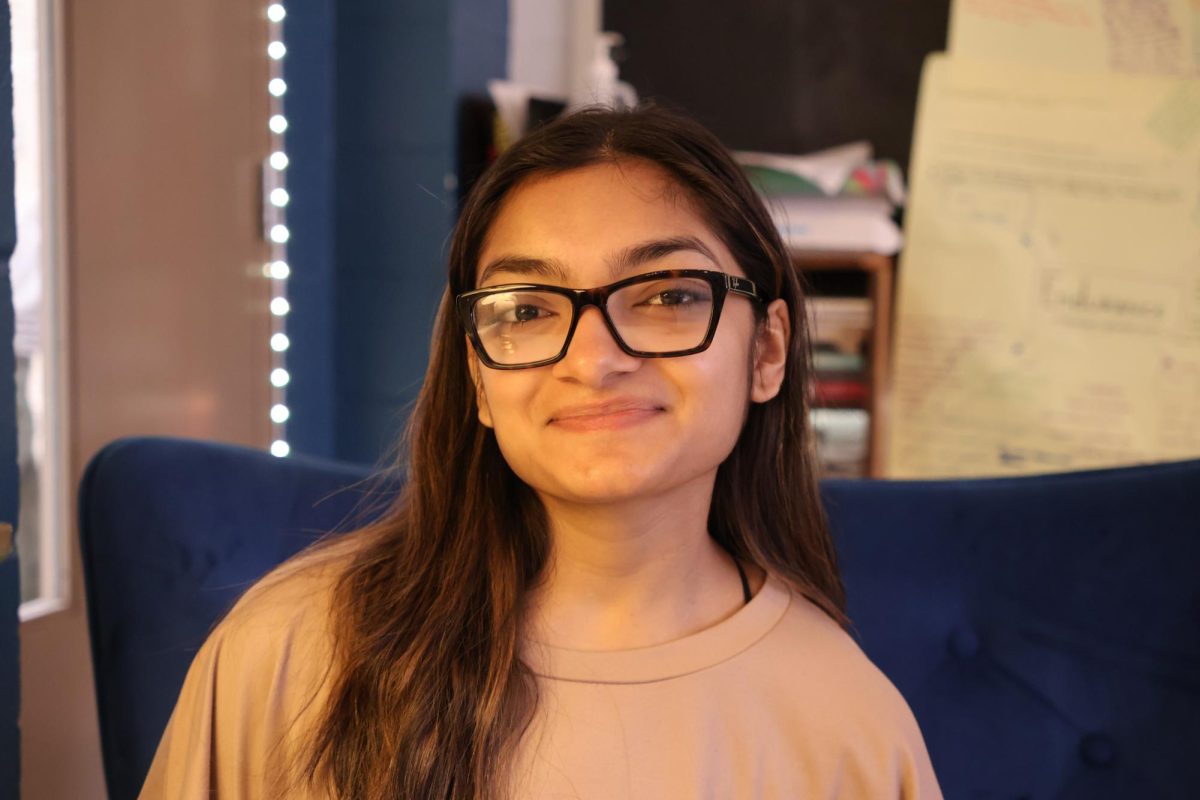

Junior Shabina Abdin supports the new policy, as it eliminates bias and ensures that “teachers will give us that right number.”

While junior Mahwish Waseem agrees with the policy, she thinks that scorers shouldn’t know the school each student comes from, since that might influence their standards.

“If teachers see ‘Townsend Harris,’ they’ll grade lower because they have higher expectations,” she speculated.

However, junior Veronica Nguyen believes that teachers from other schools might grade less harshly because they automatically have lower expectations than the teachers of academically rigorous schools.

Freshman Michelle Zalewski points out that scorers might still be able to get around the new policy and cheat, because they might grade other schools harshly in order to make their schools look better.

The ban also raised the question of whether or not standardized tests should be graded so objectively.

Spanish teacher Beatriz Ezquerra disagrees with the new policy for this reason.

“I prefer to grade my own students because I know them,” she said, noting that she still applies the same criteria to all Regents exams.

Sophomore Raina Salvatore, who prefers the original policy, agrees.

“[Our teachers] have a better idea of what we know and don’t know, and taught us the material,” she said.

However, sophomore Paula Fraczek believes that whoever grades the Regents doesn’t make a difference because in most schools, students are all taught the same curriculum, so “the grade you get is based on what you know, not on how well teachers know you.”

Social studies teacher Aliza Sherman agrees because all scorers must follow the same rubric. Although she believes that the teachers at Townsend Harris are “professional and follow the rubric,” she doubts whether other schools do the same.

Noting that some scorers may be new or inexperienced, she said, “It makes me nervous to put our tests in the hands of people we don’t know, but I hope they follow the rubric and grade fairly as well.”

This is not the only new policy aimed at cracking down on cheating. This year, the state will use Erasure Analysis of all scantrons. This system detects the number of wrong answers changed to right ones, and will be used in seventeen regional scanning facilities. They also plan to start replacing paper tests with computerized ones by 2015. The changes will collectively cost 2.1 million dollars.