Quickly thumbing through the glossed wax pages of the New York City High School Directory, a blurred color spectrum meets the eyes: Bronx violet transitions to Brooklyn red, followed by the lime green Manhattan that fades into Queens orange, ending with the thin sliver of Staten Island blue.

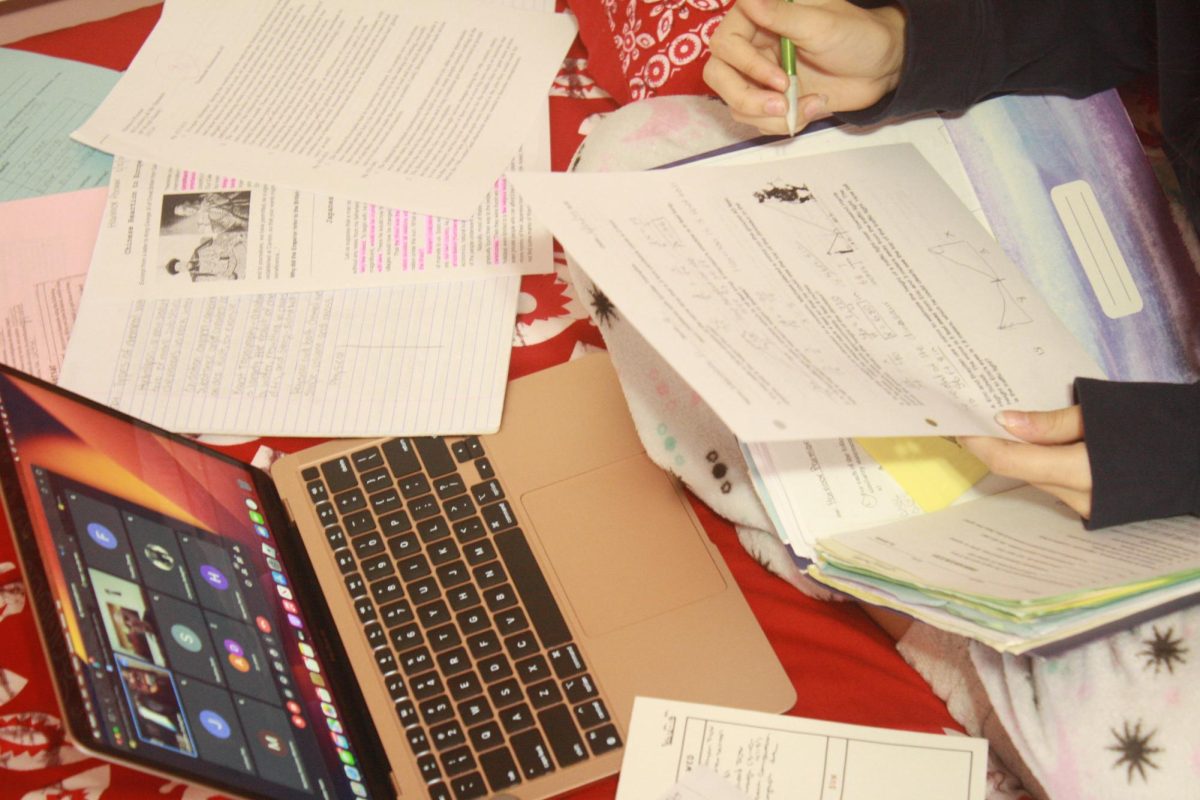

Navigating the admissions system can prove to be an acutely stressful time for students and parents alike as they consider the myriad of schools discretely summarized within the pages of the bulky admissions guide—there are over 500 New York City public high schools that are making admissions decisions for approximately 70,000 applicants. On June 8, middle school students received notice of their high school admissions results and on June 16 and 22 Townsend Harris’ admitted class of 2026 came to visit during open-house events as they embarked on the difficult task of deciding which school to attend.

But more than the anxiety that comes during the 8th grade when students apply to high school, experts have been expressing concern for years that the selection process itself leads to an increasingly segregated and inequitable school system. Two tiers of application have come under fire recently: the single standardized exam used for admission to eight of the city’s specialized high schools, and the use of a somewhat broader set of academic standards for the over 100 high schools that are considered to be selective. There are problems with each style of admissions, and solutions have been offered for each, which also include outreach to middle schoolers and changes in both middle school and high school curricula.

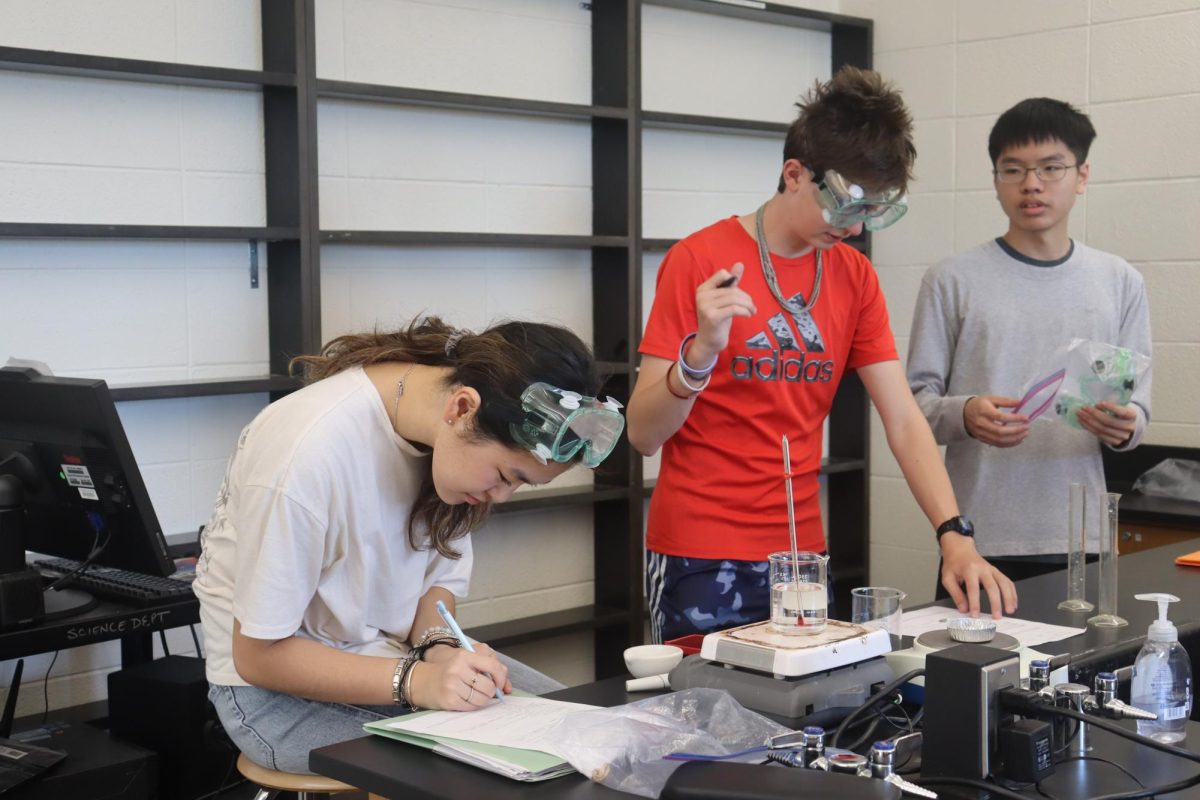

Academic screens employ an evaluative assessment of potential candidates to identify students that fulfill the academic standards to gain admittance. Many schools use them in various forms and different capacities, however those who criticize these methods tend to cite screens as responsible for perpetuating inequalities while feeding elitist attitudes supposedly founded on false meritocratic principles.

In light of the contentious debate surrounding the topic, many have proposed possible solutions that can help alleviate the problem of racial segregation that looms over the selective admissions system. The Classic spoke to two experts on the matter as they delved into how to strike a balance between pedagogical equity, namely welcoming school cultures and inclusive curricula, with diversifying admitted students in an academic arena flooded with screening measures.

The Specialized High Schools Admissions Test

At eight of New York City’s nine specialized high schools, a single state-administered entrance exam, the Specialized High Schools Admissions Test (SHSAT), is used as the only criterion for selection. (The ninth school, Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts, relies on an audition instead.)

Due to concerns regarding disproportionate representation, Mayor Bill de Blasio proposed dismantling the SHSAT system in 2018.

“I think the very fact that we’re talking about screening is an issue. Why are we screening kids in a public school system? That is, to me, antithetical to what I think we all want for our kids,” said then-NYC Chancellor Richard Carranza in a 2018 press conference announcing de Blasio’s plan.

Some experts argue that a system that relies on a singular measure for admittance, such as the SHSAT, is detrimental to the accessibility of education. Such a process is “very problematic because there’s no opportunity, whatever that measure might be, to have a real sense of what that student is capable of or wants to engage in,” Dr. Limarys Caraballo, an Associate Professor at the Department of Curriculum and Teaching in the Teachers College at Columbia University, said of the SHSAT.

At the heart of the issue with this type of admissions process is it entrenches inequalities into its practices by confining the scope of academic merit to “arbitrary cutoffs” instead of criteria that showcase “people’s hunger, desire, and capacity,” Dr. Michelle Fine, a Distinguished Professor of Social Psychology, Women’s Studies, and Urban Education at the CUNY Graduate Center, told The Classic.

Academic Screening

As an alternative to the singular entry-exam, schools like THHS, Hunter College High School, Frank Sinatra School of the Arts High School, and Bard High School Early College, use special screens to admit their students. Factors taken into consideration through this particular admissions process can entail an audition for performing arts schools, a writing portfolio, attendance, state test scores, and grade-point averages.

According to a study conducted by The Center for New York City Affairs at The New School, about 15 percent of high school students attended a screened school in the 2017-2018 school year, compared to the 6 percent that gained admission to specialized high schools through the SHSAT. Schools that implemented an academic screening system demonstrated “a considerably higher share of Black and Hispanic children, low-income children, and students with disabilities than do the SHSAT schools,” the study found.

As a screened school, THHS decided to experiment with a new admissions method with the objective of diversifying the student population in 2021, adopting the New York City Department of Education’s (DOE) Diversity in Admissions initiative. The following year the DOE mandated a new method for screening, integrating a lottery process that is beyond the school’s control.

The 2021 change came after the DOE called for a new process of admissions for the THHS class of 2025 in response to the challenges posed by the pandemic and distance learning on student development, in addition to the objective of promoting inclusivity. For that prospective incoming student body (the freshman class of this past school year), the school considered low-income students separately to account for 50 percent of accepted applicants. A ranking system remained in place as in previous years, however attendance was no longer considered and GPA carried greater heft. The most salient component of the new system was random selection: High-ranking low-income students were chosen arbitrarily to account for the first half of the admitted class, and the remaining other half of potential applicants were also randomly selected from both the top candidates in the low-income group and other students. DOE rules and regulations bar race, religion, ethnicity, or gender from being direct factors of consideration for admissions, but this new system was adopted in an indirect effort to increase diversity.

The applicants in the class of 2026 round of admissions underwent a similar lottery, save that the process for ranking students for admissions was decided centrally by the DOE and was mostly the same for all screened schools (based on a common rubric for all students).

Notwithstanding these changes, this new admissions process has yielded modest changes. Last month, The New York Times reported that THHS “made 23 percent of its offers [this year] to Black and Latino students this spring, up from 16 percent last year.”

These recent concerted efforts to diversify high school admissions have called into question the merits and limitations of screened methods in general. According to Dr. Caraballo, while screening presents multiple issues, a wider range of academic metrics involved in identifying prospective students through school screens offer more opportunities for underrepresented groups than initially acknowledged. Measures such as interviews and application materials give “a better sense of the whole student” and “help to make admissions more equitable,” she said.

However, there are still considerable strides to be made with this approach since many students are discouraged from applying or accepting offers to selective schools out of fear that they “might not be supported” or “feel they might stand out in a way that makes them feel uncomfortable,” Dr. Caraballo said.

So what solutions are there?

“There are many things that can be done and they involve working on the school culture as a culture that would be able to recognize that academic rigor looks differently in different places. Academic rigor is not a neutral concept,” Dr. Caraballo said.

In a similar vein, “So one thing is opportunity programs for kids who are coming from under-resourced or not very rigorous middle schools to prepare them for what rigor feels like,” Dr. Fine said. “We should be working with a very stretchy notion of rigor.” She suggests taking a wide range of non-academic factors into account, such as “deep student inquiry and a serious dedication to reading, writing, producing, speaking, researching, and analyzing.”

Dr. Caraballo noted that reaching out to families and underrepresented communities in languages they can understand is a key strategy for recruitment efforts. “Schools that already have a broader range of screening measures that they take into account could focus more on recruitment and reaching out to families and students who may not otherwise already feel like they would belong in the school and that would increase the diversity of the admissions pool,” she said.

When scouting schools and engaging in middle school outreach, it is important that schools overhaul stereotypes that could discourage students from applying, Dr. Fine said.

Dr. Caraballo additionally mentioned that while outward measures to demonstrate solidarity and portray a school as an inclusive space is a step towards fostering familiarity among underrepresented communities, the school runs the risk of appearing superficial if not reinforced by internal actions. That includes professional development for educators and the cultivation of a “critical consciousness” in students, a term coined by philosopher and pedagogue Pablo Freire to describe a pupil’s ability to hone in on and understand the social influences that mold their interactions and the world around them.

A diverse class with an improved curriculum

Last year, The Classic published an opinion piece by alumna Ariana Vernon, who described receiving racially charged comments that her admittance to Harvard University could be reduced to Affirmative Action. “It is admirable that the team hopes to diversify admissions, but can the team promise that newly admitted Black students will feel welcomed and included in the THHS community?” she wrote. “Can they promise those students won’t work hard for four years only to be told one day by their peers that they have not earned their achievements?”

To counter such negative student experiences, Dr. Caraballo emphasized the need for school administrators to inculcate an awareness about imposter syndrome and how people may contribute to its harmful proliferation. This, she said, is imperative to engendering a welcoming academic and social space for a multicultural school community.

“I think that, if a school is serious about being inclusive, then they will take on those topics straight up, so that by the time some insidious message circulates, it’s already been addressed front and center,” Dr. Caraballo said. Posing the risk that those exposed to harmful messages are left “vulnerable and alone,” she said it is crucial that schools do not allow the development of a critical consciousness to be something “that youth should be forced to seek on their own.”

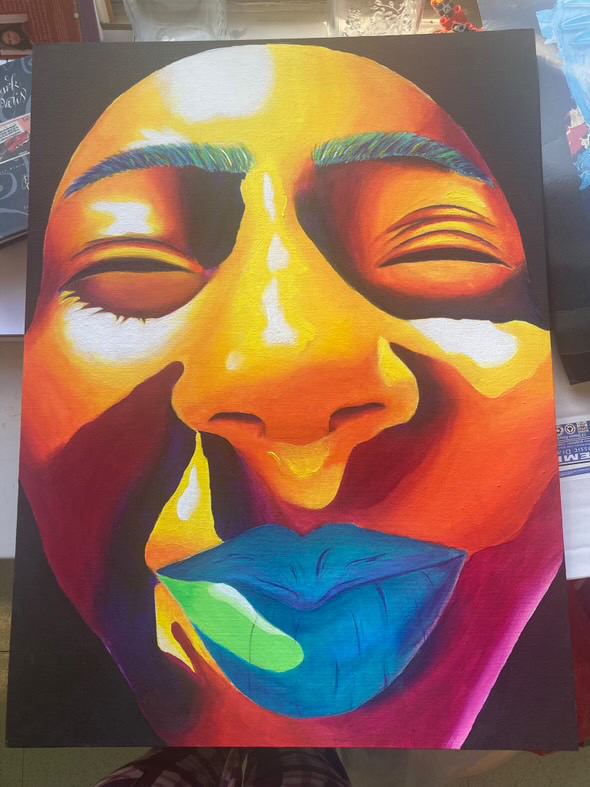

Dr. Fine highlighted the importance of schools integrating a culture that is culturally responsive. “Rigor needs to include that, it can’t be set up as oppositional. Elite schools are built on a culture of competition and they often nourish it,” she said.

In order for a culture shift to occur, schools should be made “more inclusive and culturally responsive and sustaining so that then you can invite students into something that already exists and invite them to cobuild,” Dr. Caraballo said.

She also mentioned a curriculum that evaluates real-world social structures and can bridge the gap between critical consciousness and the high school curriculum. This involves “integrating what we learn about social issues and justice related matters with how that’s implicated with everything that we do.”

The DOE is currently developing a Mosaic curriculum as one measure proposed to diversify the high school curriculum with “an unprecedented infusion of books into every classroom for next school year,” the DOE website reads. “Currently, there is no single off-the-shelf curriculum academically rigorous and inclusive enough for New York City’s 1,600 schools and one million students. This curriculum will be built on Literacy for All, accelerate student learning, and free teachers from time-consuming curriculum development.”

Dr. Fine said that although conversations about equity and rigor often render the two as incompatible, she calls them “redundant.” “The question is what would we teach, how would we teach, and how would we assess if we were serious about both,” she said. “How would we design classes so that the gifts students bring are part of the resources and productivity of a school. How would we assess your knowledge through performance-based assessments and participatory inquiry.”

Dr. Caraballo maintained that schools should prioritize listening to their students in order to effectuate meaningful progress. “The students can offer a wealth of knowledge about what they are experiencing,” she said. “I think that, if we had more mechanisms for young people in schools to be able to communicate what they feel, what they need, what they experience, and what they desire, then there would be more dialogue and probably a lot more substantive change and reform.”