How the Pandemic Changed Your Brain: Study shows that COVID shutdown quickened development of teenage brain structure

A new study reveals effects of the pandemic on the brain, and Harrisites share their feelings about it.

Adolescence is a critical period for brain development; in the shift between childhood and adulthood, this organ is particularly receptive to its environment. So, it makes sense that when the world suddenly plunged into a setting of solitude and distress, the brains of pandemic teens reacted. A recent study published in Biological Psychiatry: Global Open Science late last year found that teens’ brains had undergone rapid development over the course of the pandemic. In the face of new mental challenges, such as feeling isolated from friends and constantly fearing for their own health, their brain structure experienced premature growth in fundamental areas for emotion.

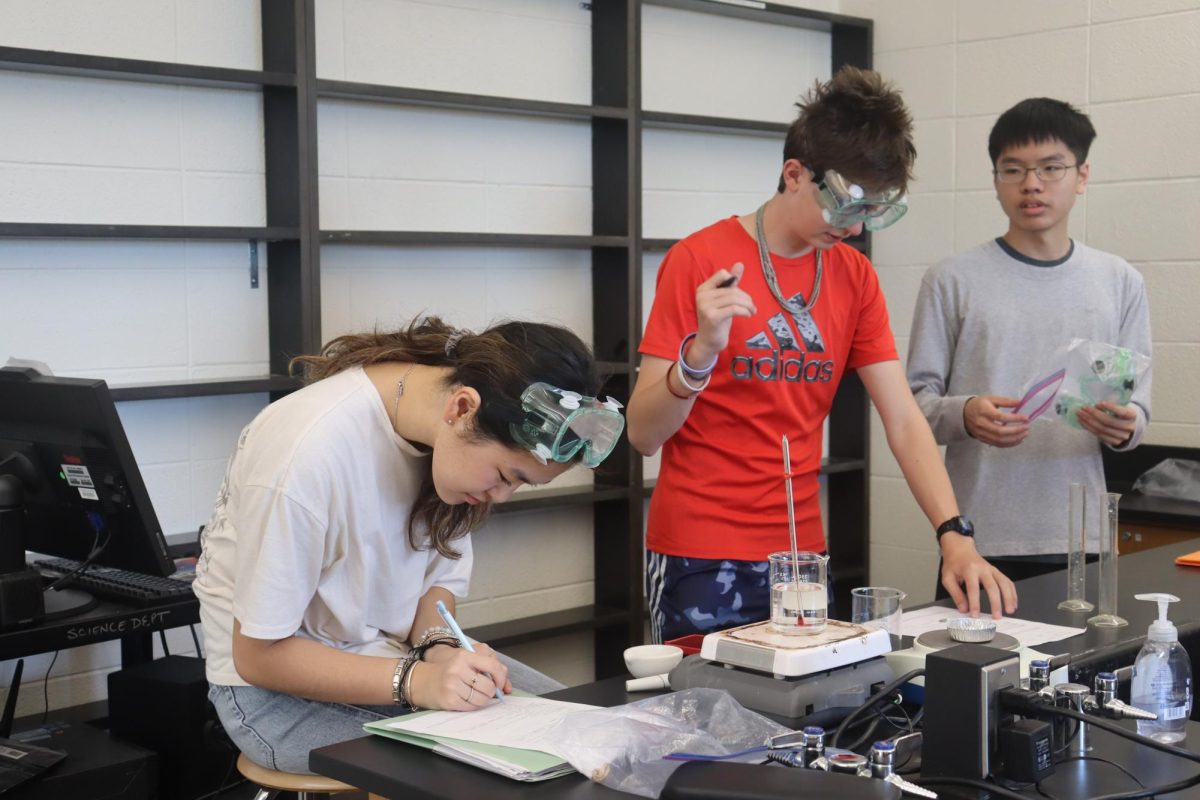

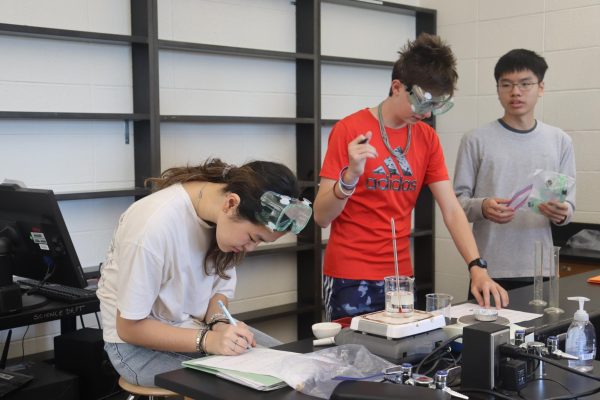

The discovery wasn’t completely intentional – it was stumbled upon by scientists from Stanford University who had originally intended to conduct an experiment on the effects of stress on the brain throughout the stages of puberty. The experiment was pushed back due to the pandemic before completion, however. Once the scientists were able to collect data again, they noticed a stark difference between the early MRI results and the newly collected scans. Upon their realization, they decided on a new area of research.

The researchers were able to compare the MRI scans of 163 adolescents from before the pandemic to follow-up assessments done a year after the pandemic had started. Neuroimaging results showed that the cortex, the part of the brain that controls human cognition, had thinned, which indicated that it had aged a significant amount due to a disturbance in social interaction. Additionally, the hippocampus, an area that operates memory and emotion, had grown in order to sustain the mental deprivation.

One significant difference in the self-reported mental health difficulties was the difference in symptoms of anxiety and depression. The group tested during COVID, or peri-COVID, were reported to have more than a 10% increase in internalizing mental health problems, expressed in severe anxiety and depression symptoms.

The researchers analyzed the measurements of several regions in the brain to reach their conclusions, which were referred to as brain metrics. The results of the brain metric analysis showed that there was an overall decrease in the cortical thickness of the peri-COVID group compared to the pre-COVID group, referring to the width of the human cerebral cortex, a highly folded sheet of neurons also known as gray matter. Neuroimaging research indicates that there is a positive association between intelligence and cortical thickness.

One of the most eye-catching findings was the variation in the brain age gap estimates (brainAGE) of the two test groups; brainAGE is an estimate of the difference between the predicted age and the chronological age of a brain. The group living during Covid had significantly older BrainAGEs than the pre-COVID group, meaning their choices, emotions, and thought processes were ones that are typically experienced by people older than their age. The test results also showed larger bilateral hippocampal and amygdala volumes, as well as increased advanced cortical thinning. All of these factors contribute to accelerated emotions and a higher risk of depression and anxiety. Overall, it seems that the events of the pandemic increased the chances of children experiencing anxiety or depression at as young as 12 years old.

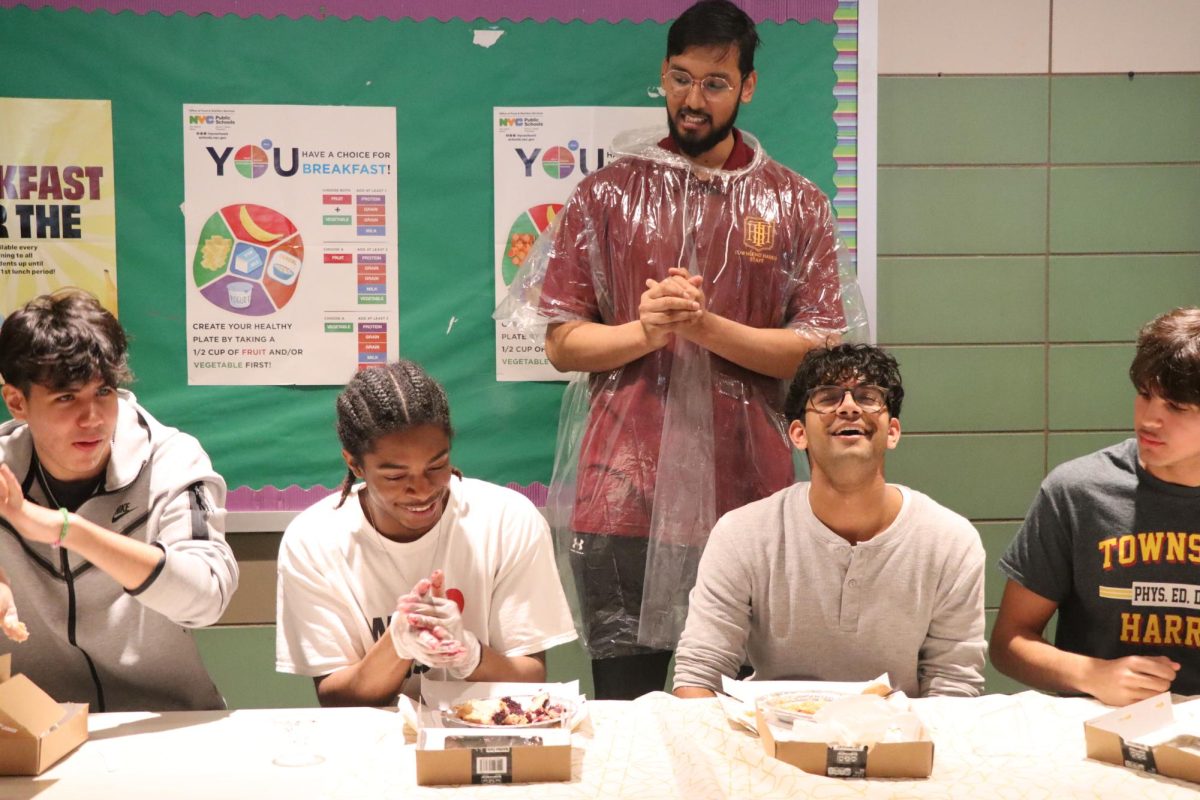

Although all the youths in the experiment were from the San Francisco Bay Area, students at Townsend Harris can attest to experiencing similar struggles with mental health following the lockdown. “The pandemic has left me feeling a bit off track, and the sudden social deprivation caused difficult times,” said sophomore Ramon Rivera.

“As an extrovert, being isolated 24/7 made me feel like I was going insane,” said senior Arietta Xylas. “I definitely became significantly worse at regulating my emotions – I’d cry so much that I could log it. I began wondering if I had anxiety because everything just felt so overwhelming.”

In contrast, some students liked the relaxed atmosphere of the pandemic. “I’m the kind of person who likes staying at home rather than going out anyway,” said junior Amy Jiang. “I didn’t really feel alone because I had friends to talk to, even if it was just on the phone.”

These discoveries raise concern over how this generation’s neurodevelopment will mature in the long run – whether or not their brain will return to a lower brainAGE is yet to be determined. It’s possible their brain metrics will remain altered, always ahead of their chronological age, which could affect their behavior in the future or result in the early development of brain diseases. The researchers at Stanford mentioned that these changes could also interfere with long-term studies of normative development that will include data from over the course of the pandemic.

Despite the adversities students have met in the past three years, some have been able to gather themselves and recover thanks to the relative return to normalcy. “Once I got back to school, I couldn’t stop talking to everyone. I felt infinitely better, like who I was before,” said Arietta.

Ramon said, “Now that I know I am not alone, I feel we can help integrate ourselves and better handle situations like the pandemic caused.”

Your donation will support the student journalists of The Classic. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment, support our extracurricular events, celebrate our staff, print the paper periodically, and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Ayoub is a senior at Townsend Harris High School. He loves playing chess, table tennis, and wrestling. He loves to take care of cats and to travel...

Samira is a senior at Townsend Harris High School. She’s been into photography since joining the Classic and loves to explore new cameras. She enjoys...