Is ChatGPT upending learning? Survey shows most THHS students are unfamiliar with the AI, but some have begun using it for class

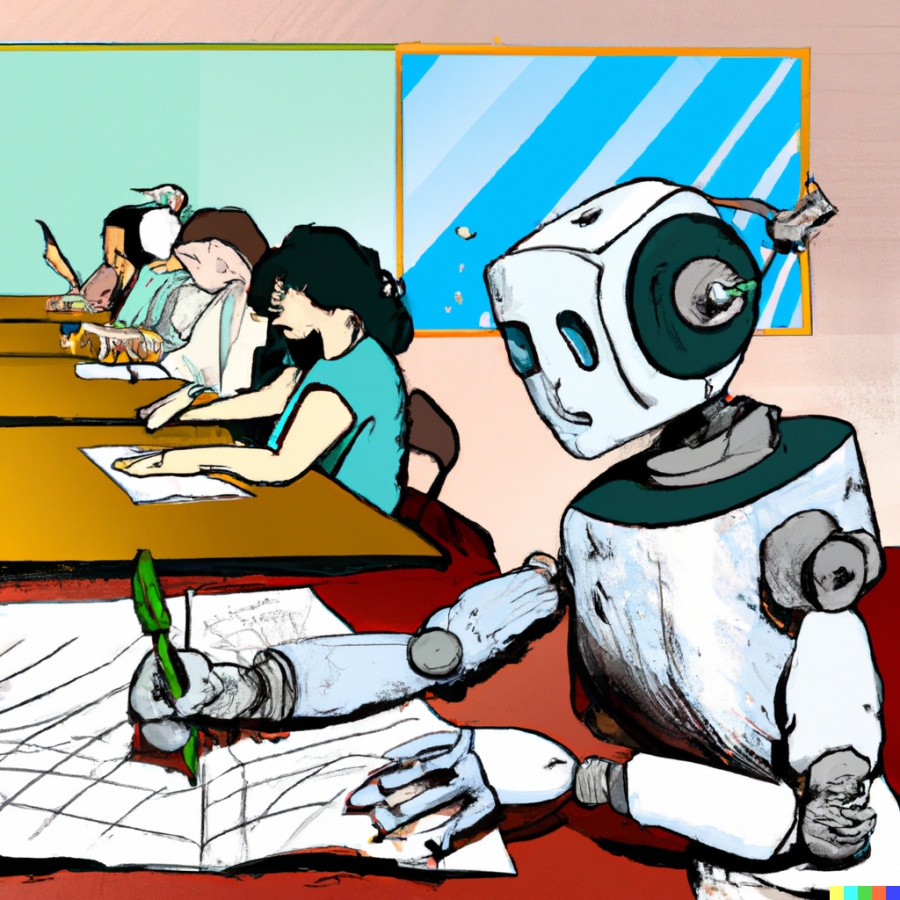

ChatGPT, a conversational application of OpenAI’s GPT-3, widely regarded as the most advanced A.I. in the world, has been heralded as a tool with unmatched and seemingly unlimited applications. Since its release in November, the program has caused an uproar. Its ability to mimic writing nearly identical to that of a human being has set off waves of media attention and speculative frenzy. One of the primary concerns raised was the newfound convenience for students to use A.I. to write their essays and other written assignments and pass it off as their own, posing a potential threat to education systems around the country. Some have gone as far as declaring the death of the student essay.

The Classic conducted a survey to determine how familiar the Townsend Harris student body is with the technology, and whether students have been using it to submit work. In the anonymous survey, distributed to more than 300 THHS students across 12 randomly selected classes from grades 9-12, 36% of Harrisites said they were aware of ChatGPT’s existence, and 14% of the students who have heard of it reported using it for schoolwork.

The Classic spoke to two students at length who admitted to using ChatGPT for school. The first, a senior who asked not to be identified, said after hearing about the program through TikTok, they posed a random question to see how it worked, and the chatbot was able to produce a coherent response. The student later used it to generate talking points for a Humanities journal assignment, which the student then added to with their “own evidence and analysis.”

The uproar concerning ChatGPT in regards to American education largely stems from the program’s ability to produce original, untraceable work in seconds. Since the A.I. writes its own response, student plagiarism would go undetected, since the content wouldn’t be available on any databases.

The same student also tried using the tool to write an essay required for part of their college applications, and the results were disappointing; the answer “ended up being so generic. It didn’t pertain to anything about myself,” they said. Overall, the student concluded the exercise was not helpful. “If you did it yourself, you would probably have a better answer than ChatGPT,” they said.

Growing discussions about the impact of new technologies in classrooms have coincided with concerns about academic dishonesty. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic that pushed schools into remote instruction, plagiarism has grown more prevalent in schools, frustrating educators and hindering student learning.

When asked about the impact on education, AP Research teacher Cris Hackney said ChatGPT’s role in generating essay responses can potentially undermine the benefits of school and its role in preparing students for the real world. “I am not sure about how it could be positively used, because to me school is the place where you basically learn how to do stuff. It’s the forum where you want to do things yourself, you want to make mistakes and mess up here so that you can become better,” Mr. Hackney said.

For some students, the technology is as frightening as it is to educators.

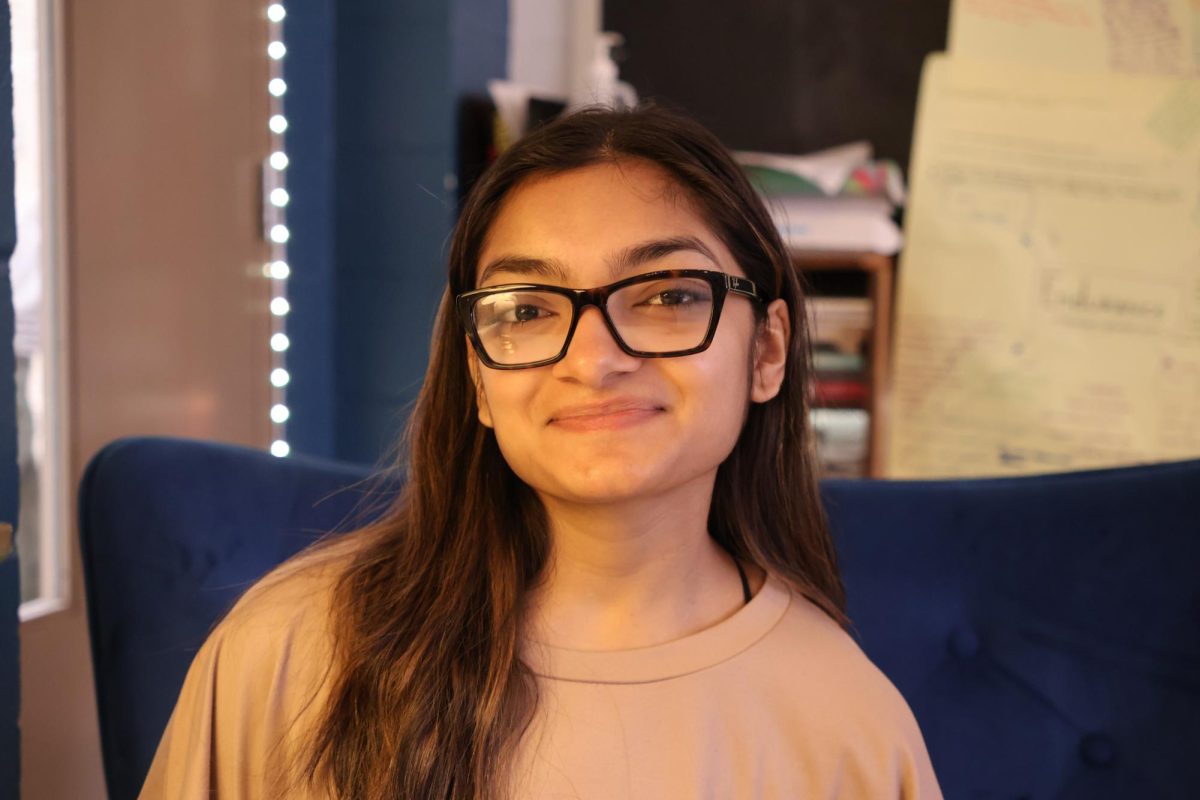

“It is kind of scary how advanced technology has become,” said freshman Jenna Abdelhamid. “I fear this will replace students using their own skills and free thought.”

Senior Jolin Huang said that students using ChatGPT may “have consequences down the road, especially if they’re cheating in higher education [courses].”

For the second student who spoke to The Classic and asked not to be identified, the program’s use primarily entailed saving time on certain assignments. They explained that using the A.I. was most effective when it came to busywork, or assignments that require less critical thinking. They said, “I can give it a set of terms and it’ll define them for me. That just saves time.” They added that the program falls short in tasks such as “quoting and explaining the author’s perspective.”

The student specifically mentioned an instance where they cheated with ChatGPT by asking it to write a one-page speech for a history assignment, and the results, they said, were exemplary. They said that in their experience, the program worked best on outlines and assignments that did not require textual evidence or a specific style of writing to complete. For literature-based assignments, “sometimes it’s a whole lot of nothing,” they said.

As media coverage of A.I. has consistently dominated news cycles since the technology made its debut, fears surrounding its facilitation for academic dishonesty have caught fire, and education networks across the United States, including those in Seattle, Los Angeles, and New York City, the largest public school district in the country, were quick on the draw to ban ChatGPT from their servers.

In The Classic’s survey, 16 students out of the 312 admitted to using the program to submit work for school, and four to complete an entire assignment, a small fraction of the 116 who had heard of ChatGPT at all. Despite the recent flurry of media declarations about the technology, whether or not it has completely upended high school academia remains to be seen, according to the initial response from Harrisites. Though the number of students who said they use it is small, it is possible that students chose not to respond to the survey honestly and were intimidated by filling it out in a classroom setting with a teacher in the room.

Out of those who did know about ChatGPT, the main source of information was social media and word of mouth. Many respondents reported hearing about it through TikTok and others said they heard about it through friends.

Most of those surveyed, when asked about their overall thoughts on ChatGPT, expressed excitement about its uses, but many mentioned their concerns on how it could facilitate cheating. “It is a cool piece of tech,” said junior Vivian Chen. “but it will ultimately harm the student’s ability to write and think critically.”

English teacher Kevin McDonaugh said that though ChatGPT does make it easier to cheat on written assignments, it doesn’t spell the end of humanities-based education by any means. “There have always been methods for students to submit disingenuous work,” he said. “When I read a student’s essay and I compare that with something written by A.I., it’s pretty apparent when something is not written by a person whose writing you’re familiar with.”

Mr. McDonaugh, who is also THHS’ teacher union representative, mentions ongoing collaborative efforts between the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) and software companies currently working towards developing guardrails against the dishonest use of chatbots in education, such as adding identifying watermarks on the page. OpenAI has also recently released a “work-in progress classifier” that attempts to detect text generated by A.I., and is actively working on refining the tool to function better in future iterations.

Recognizing that A.I. is here to stay, Mr. McDonaugh said unions also had talks with these companies about the ways these technologies can be positively harnessed in the classroom with the proper oversight. Educators around the country, in fact, are already using the chatbot to test students’ media literacy, provide instant feedback to student writing, and even help write exam questions.

For all the speculation circulating online and in the media about the consequences of ChatGPT, the projected impact is not near conclusive. The program undeniably poses significant hurdles to educators, and cheating is now more convenient than ever before. But the A.I. has not toppled the teaching world, at least not during its first three months since conception. As for the THHS student body, the true effects may be too soon to tell.

Additional reporting by Sadeea Morshed, Carina Fucich, Isabel Jagsaran, and Hana Arafa

Your donation will support the student journalists of The Classic. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment, support our extracurricular events, celebrate our staff, print the paper periodically, and cover our annual website hosting costs.