By Laura Marsico, Mohima Sattar, and Ashley Sealey

DONNING BLACK from head to toe, only her face and hands visible, a young Muslim girl makes her way to school. She and a current of other floating heads rush along towards the same destination. To these people, she is just another student. At Townsend Harris, she is one of many Muslim students, and wearing an abaya wouldn’t immediately turn heads or yield rumors.

The same girl now walks down a busy street with her mother, a woman clad in a burka, only her eyes visible. They cross paths with an older white man, and are instantly propelled into a very different situation. Rude comments arise at an ever increasing volume, accompanied by hand gestures as he yells, “Go back to where you came from.” At one point, the girl fears he will spit at her.

Junior Sangida Akter is a 16-year-old girl living in New York City. She shares this home with nearly 8.4 million people, many of whom identify with the Islamic faith. Her experience walking the streets of this city is not an isolated one.

In a range of conversations with current and former Muslim students at THHS an alarming number report being harrassed in the street, intimidated, and in one case, physically assaulted.

According to reporting by The New York Times, hate crimes against Muslims have tripled since the terrorist attacks that struck Paris and San Bernardino, California at the end of last year. Such attacks coincide with increasingly sharp rhetoric from presidential candidates, with Donald Trump’s comments drawing the most attention and controversy. In December, Trump called for a “a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States.”

Behind this climate is the assumption that Muslim-Americans are a singular subset of American society, one that can be lumped together, but there are few places that provide a picture that so clearly opposes this monolithic stereotype as Townsend Harris.

New York has one of the largest Muslim populations in America, and within New York City, the largest concentration of Muslim Americans is in Queens. Unlike most schools in Queens, THHS pulls in students from all over the borough, ensuring that our population of Muslim students comes from a wide array of places within Queens. This puts Townsend Harris in a unique place within the country to report upon the nature of a group that has the rest of the nation talking. With this in mind, we sought to explore the experiences of these Muslim Harrisites at this moment in American culture and politics, and to explore in depth key aspects of their experience here at THHS that distinguish them from wider images in the media.

WEARING THE HIJAB

One of the most prominent examples of diversity within the Muslim community at Townsend Harris involves the decision to wear a hijab. While many may assume the hijab to be a mandatory part of clothing for Muslim women, for many it is a matter of choice.

Junior Noorshifa Arssath is Sri Lankan with Portuguese and Turkish descent, “and grew up in a household that taught [her] to do anything [she] set her mind to.” It was her own choice to wear a hijab. It is an outward demonstration of her faith—a clear label that she is Muslim— and she realizes that oftentimes it puts her under a spotlight. “In the outside world I have to live up to a double standard. I walk into the train and there are times when no one will want to sit with me or near me.” She has been shouted at in public, and called a “terrorist.”

She is steadfast in her belief that her hijab is not only what defines her as a Muslim: “Wearing the hijab or growing a beard doesn’t make you more Muslim. My dad doesn’t have a beard. He chooses not to, but deep inside he has a strong faith.”

Junior Mithila Hossain, who is of Bengali descent, started wearing the hijab a couple of years ago, but no longer does, stating, “I feel more comfortable with myself by not wearing it and happier, but maybe in the future I’ll start wearing it again with pure intentions.” While she does believe that wearing a hijab is no guarantee of being a Muslim with a stronger faith, she did concede that “if peo- ple see you wearing a hijab or something that clearly portrays that you are Muslim, they will tend to be more racist towards you. Even though I don’t wear the hijab, I’ve witnessed lots of people harassing women who wore hijabs in public and made negative remarks against them and Islam.”

Sangida, in her abaya, feels on display at many of the events that are normal for high school students to attend. At an academic conference, she can’t help but note the bewildered looks from people who underestimated her, believing she was “narrow minded and not involved in general American culture.” She too is an American; she has strong ideals, she has varied interests, she is a feminist, and she is a scholar. And yet, there are times when she believes she has to face an “unnecessary hard time and still have to stand there and put in an extra smile and say please and thank you,” in a desire to avoid further tarnishing the person’s already distorted views on Muslims. “In those times, I’m at my most vulnerable and wonder why an extra piece of clothing makes me so very different in other people’s eyes.”

She also discussed how different groups treat her: “If I had to be frank, I think little kids are the people I feel most comfortable being around as a woman in a headscarf in public. It’s absolutely beautiful how children are so easily able to see you as who you really are: just another human.”

Senior Tahina Ahmed remarks, “people see the hijab and they automatically associate you with ISIS or some kind of terror organization. It’s the worst.”

At THHS, the co-president of the Muslim StudentAssociation (MSA) is senior Sarah DeFilippo, who does not wear a hijab and is actually from Trinidad, a country in the Caribbean. She states, “I don’t really face a lot of outright discrimination outside because I’m light-skinned. I only speak English and Spanish,and I’m not a hijabi.”

ETHNICITY AND RELIGION

Beyond the issue of dress is the general “ethnic look” that popular images of Muslims suggest can only be Middle Eastern. Yaseen Mohamed has Egyptian and Ecuadorian backgrounds, and follows many Islamic practices including fasting during Ramadan and refraining from eating pork.

Muhamed Bicic, junior, is from Montenegro, a country in Eastern Europe: “For the most part, I don’t get much of a reaction when I tell people that my name is Muhamed. Very rarely do people comment something regarding my name. I recall being asked, ‘How can you be Muslim if you are white?’” Noorshifa herself admitted to being surprised on the first day of school when she found out what Muhamed’s name is. “I think that people are quick to assume that Muslims have a distinct look, but religion has no race or specific look. Anyone can be Muslim regardless of where they’re from and who they are.” Muhamed went on to say that he believes that society in general plays a role in “painting the image of Muslims and adding to related stereotypes such as having a darker skin color.”

Many students do not mention that they are Muslim until specifically asked, such as senior Abdoulaye Diallo, who remarks, “to me, religion is a personal thing—it is my relationship with God. I never really tell people what religion I follow because frankly, it’s personal. I’m not ashamed of my religion or anything of that sort; I just don’t announce my religion freely unless I’m asked about the faith I follow.”

Abdoulaye is from Guinea, and lived in France for a few years before coming to the United States.

DEPARTING FROM MEDIA DEPICTIONS

Many consider THHS a relatively safe space compared to the outside world.

This is not necessarily the norm for other high schools, as Destiny Lucas of Queens Collegiate at Jamaica High School noticed: “Recent terror attacks have caused some students to joke about [Muslim students] being affiliated with it. When the ‘native speakers’ talk amongst themselves, people become curious or nervous.”

Assistant Principal Ellen Fee finds that “NYC is a different place than the rest of America.” She continues, “We are very privileged to be in a very tolerant society, but I think that THHS is even more special and even more tolerant than most of NYC and I think our community is more open than any other community I’ve been to.”

Referencing that diversity, Muhamed states, “THHS allows us to become more in contact with cultures we might not be exposed to.”

Sangida adds, “I’ve basically grown up in South Asian and Muslim communities all my life, and though I was raised with the idea that you don’t have to be a certain way to be Muslim, I didn’t really get to experience this until I came to Townsend.”

Tahina says, “The THHS Muslim community, specifically the MSA, is wonderful. The club isn’t exclusive; the door is open to anyone who wants to come in and engage in various conversations and I feel like that’s great because it moves away from the media’s idea that Muslims like to keep to themselves. Instead, the MSA is spreading the message that we welcome people of all backgrounds and religions.”

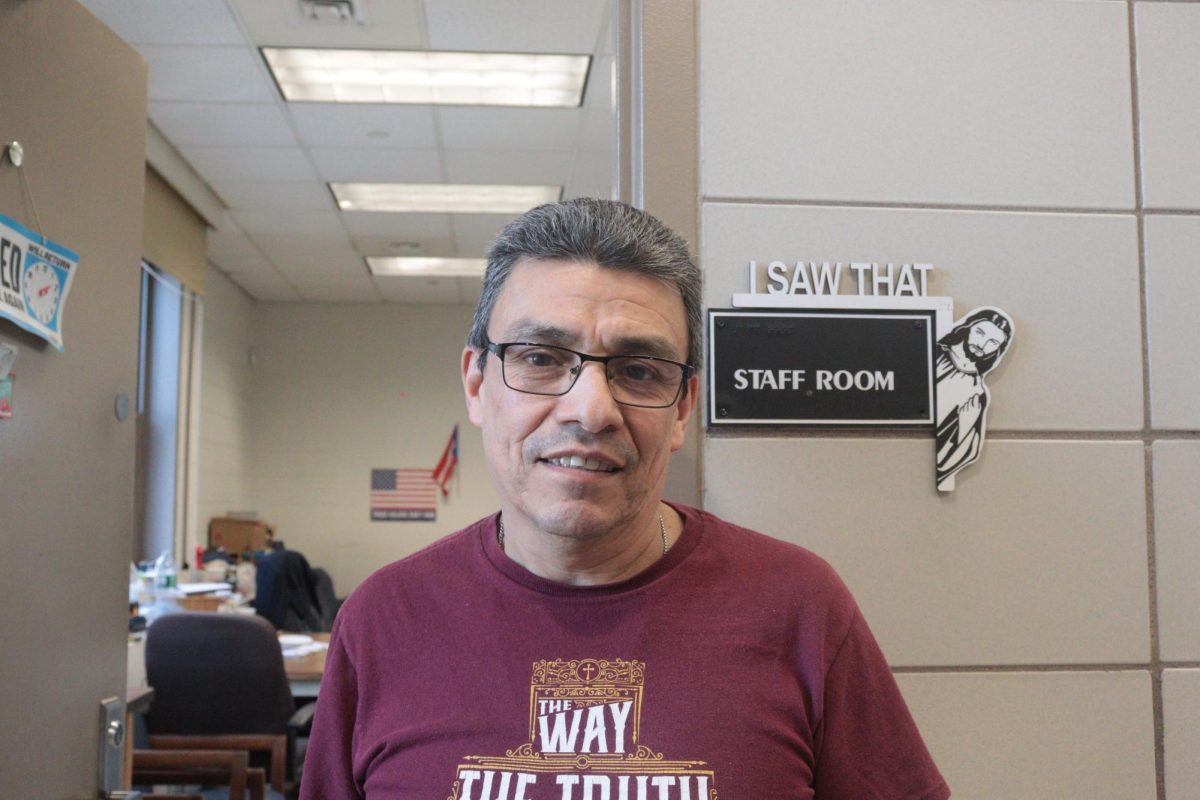

The message that students and faculty want to get across is that wearing a hijab, having dark skin, or having a long beard does not automatically make someone a terrorist. “Human beings are complex; there are ways of understanding people in ways other than through religion,” says Assistant Principal Rafal Olechowski.

Commenting on portrayals in the media, Sangida says, “Many of the Muslims I love spending time with aren’t those clad in hijabs and beards. They look and dress just like any other American and talk about the same pop culture that any other American talks about.”

“I think my major issue is that people don’t view Muslims as Americans. I can tell you for sure that I love being an American,” said Noorshifa.

She continued: “This is where I was born. It’s my country, my home. I stand up every day and say the pledge of allegiance and I even perform the National Anthem at events. If someone threatens my country, it’s my job as an American to protect it and its beliefs.”

Mithila finds that the media “never explains what’s written in the Qu’ran or what is really expected from Muslims, but rather the horrible crimes that some committed.”

Similarly, Tahina states, “I think a lot of the time Muslims are portrayed as being isolated members of their community. You’ll hear reporters say that Muslim assailants kept to themselves and were very taciturn. However, the media is just generalizing.”

Sangida said,“The media loves to portray Muslims with these serious facial expressions, which really doesn’t help the misunderstood stereotypes others have of them being people who adhere to a radical religion that’s inconsistent with the 21st century. “

She added, “When was the last time the media showed a smiling Muslim or some Muslims teenagers or children just living life?

“If the mosque in the background is really that necessary, then show the little kids playing around and giggling as they leave the mosque, not the preacher who is walking out solemnly or the prayer going on inside the mosque.”

Discover more from The Classic

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.