Recently, many colleges have returned to requiring prospective applicants to submit standardized test scores for admissions. Though test-optional policies came during COVID-19, standardized tests like the SAT and ACT continue to affect economically disadvantaged students. A more comprehensive student evaluation system that incorporates auditions, interviews, special projects, and essays is essential for a fairer and more accurate assessment of college readiness.

Since the onset of COVID-19, many colleges made the SAT optional for admissions, but this year, schools like Yale, Harvard, and Dartmouth have reinstated the requirement. When making these changes, the universities referenced the accuracy of standardized test scores in demonstrating how well a student will do at the college level. According to one study, “SAT and ACT scores have substantial predictive power for academic success in college.” In reinstating its test-mandatory policy, Harvard suggested that this “predictive power” helps to level the playing field. “Standardized tests are a means for all students, regardless of their background and life experience, to provide information that is predictive of success in college and beyond,” Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences Hopi E. Hoekstra told The Harvard Crimson.

However, this assumes that students all arrive at their testing sites on a level playing field and that the tests are completely neutral measures of a student’s intelligence and ability.

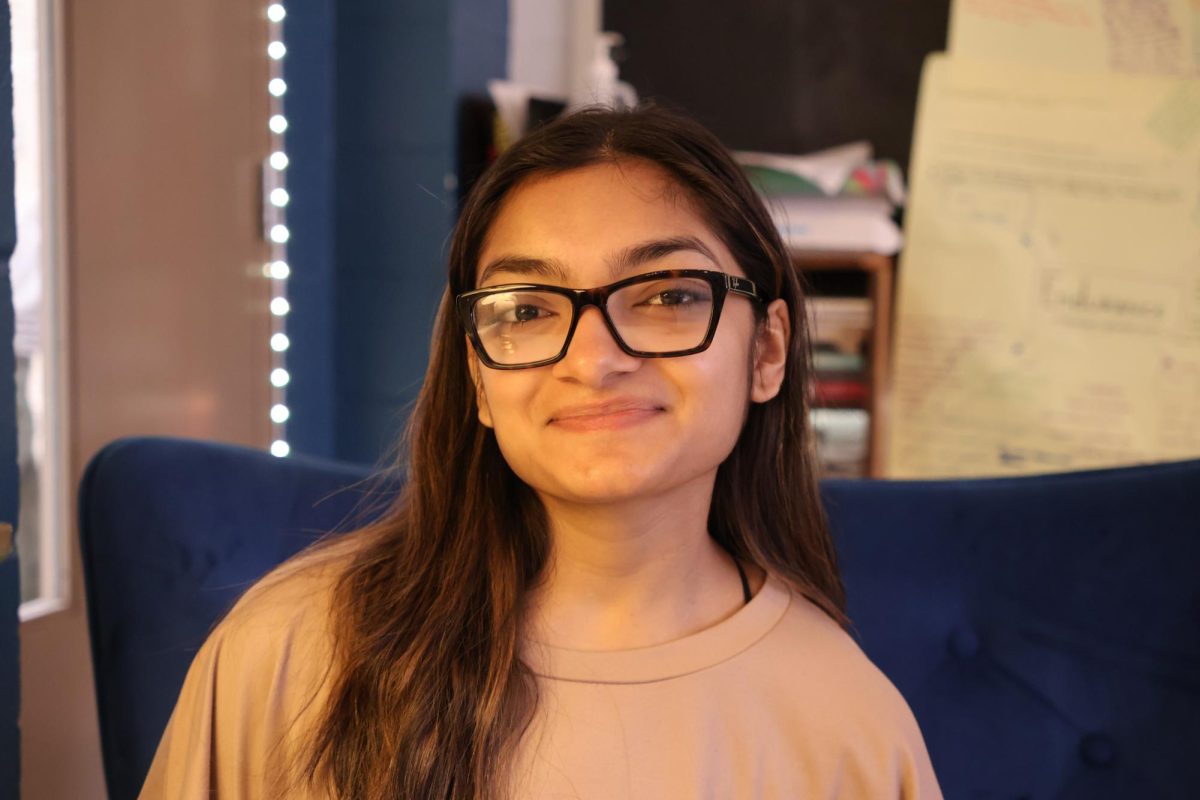

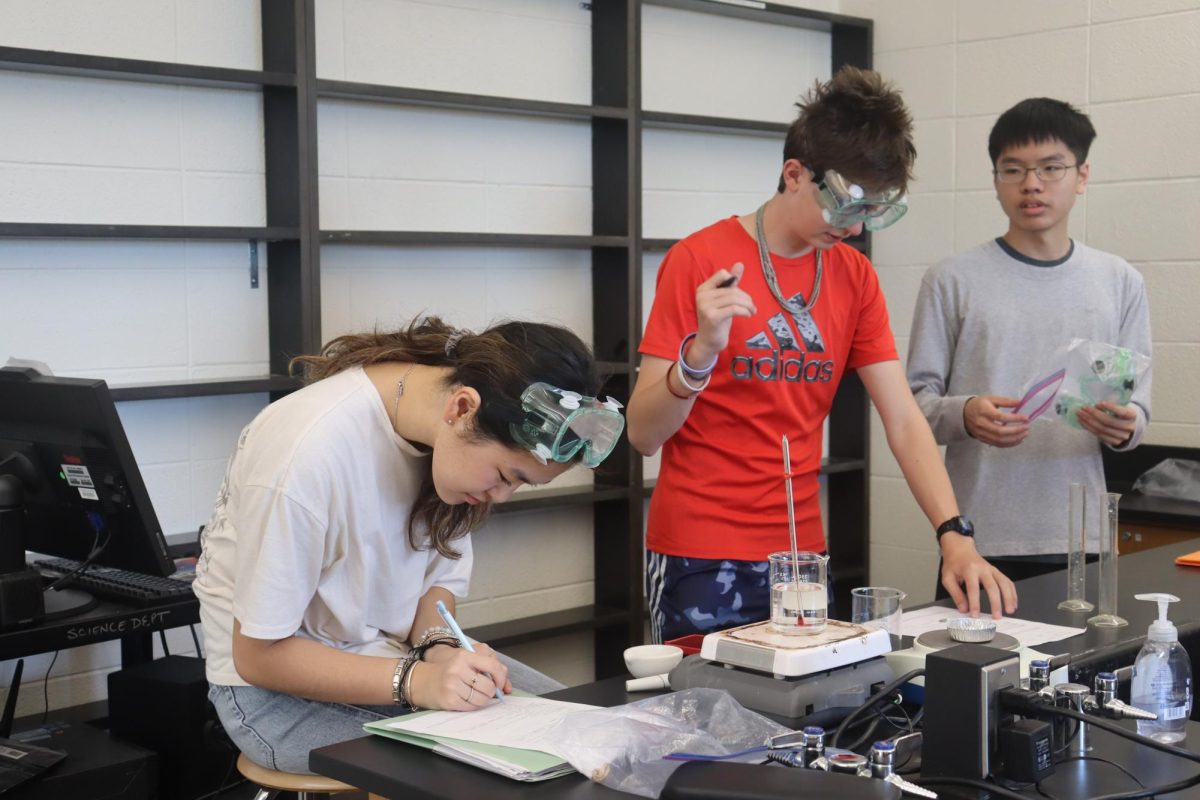

At Townsend Harris High School, there are many reasons to suggest that the SAT doesn’t accurately represent the academic capabilities of the student body. First of all, students can suffer from test anxiety. This condition can impact their performance. Anxiety can impact their mental as well as their physical health during SAT season. This stress manifests itself in various ways, including difficulty concentrating, memory lapses, and physical symptoms like headaches or nausea. The impact of these symptoms coupled with the pressure the expectation of good grades puts on students can impact performance. A study by scholars from Florida State University looked at test anxiety and performance on a state reading exam. It found that, “test anxiety was negatively associated with reading comprehension test performance.”

Given that one’s anxiety can influence their score, students who perform better on less stressful forms of assessments such as projects and writing tasks don’t get to reflect that in their SAT score, precluding them from showcasing their true strengths.

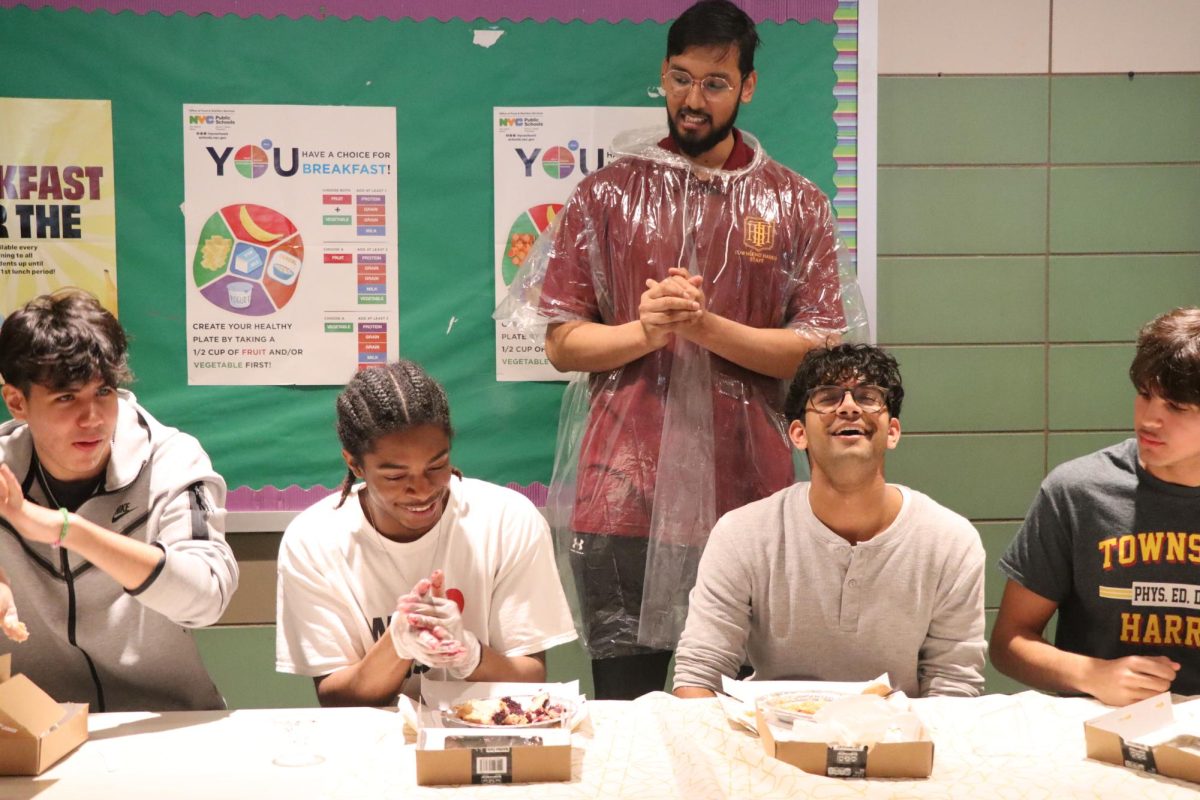

Secondly, students who attend schools geared toward humanities-based learning such as THHS, have tendencies to excel in areas such as writing, critical thinking, and creative expression.

THHS students have a variety of unique skills and qualities. The SAT, a standardized test, does not reflect these various skills. There should be alternative assessments geared specifically towards a student’s skills and talents to best assess how they perform in ideal areas of interest. Methods such as auditions, interviews, special projects, and essays provide a more comprehensive evaluation of their abilities and potential. These forms of assessment allow students to showcase their skills in analysis, communication, and creativity, which are crucial for success in many academic and professional fields. By incorporating diverse evaluation methods, colleges can ensure a more equitable admissions process that recognizes and values the unique talents of all students.

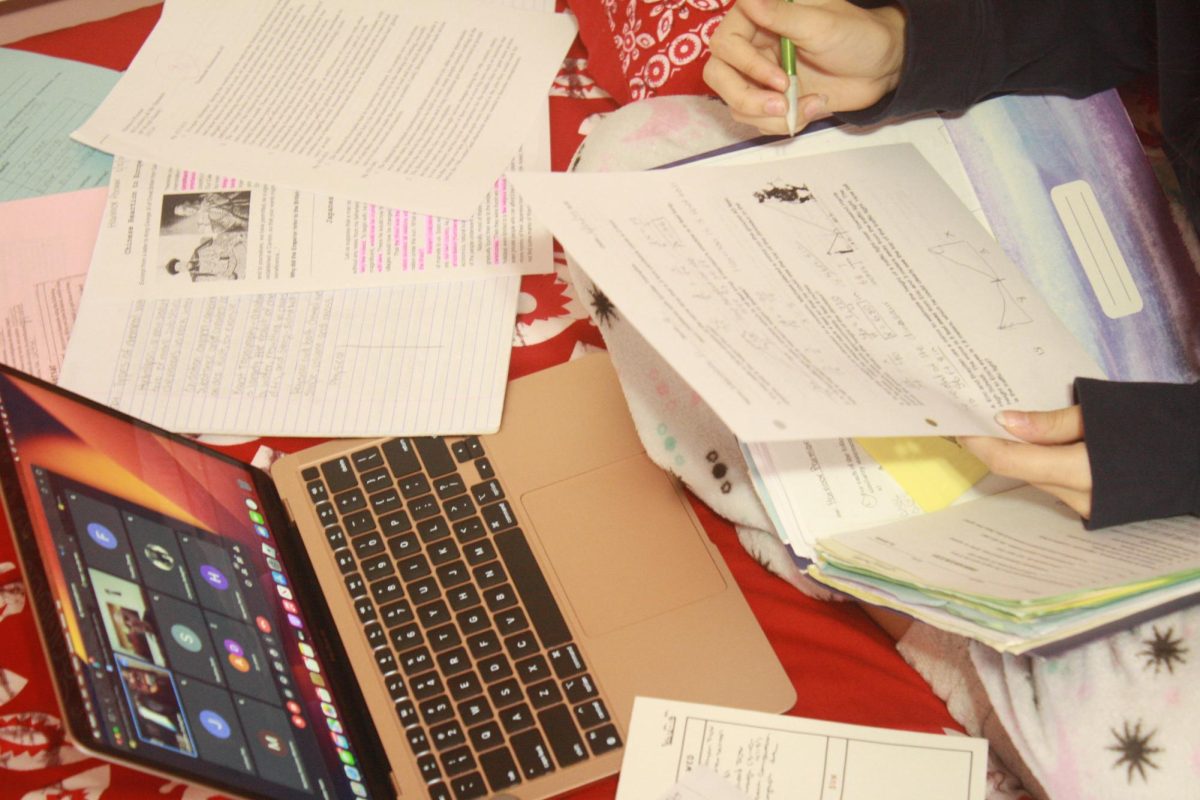

Thirdly, SAT prep programs exacerbate economic disparities, putting students from lower-income backgrounds, particularly those in NYC public schools, at a disadvantage. Most of the time, these programs come at a high cost, preventing access for low income students to get the extra help they deserve. An article from EdSource states, “This truth should come as no surprise to parents who have had to pay for expensive test prep classes or who hunted for scholarships and low- or no-cost test prep options.” This creates gray lines in the SAT scores as students of wealthier backgrounds are to get the help needed to score well compared to a not-so-well off student who can’t afford the help needed to do well. These students can’t perform as well on the SAT due to having to rely solely on self-studying and school resources. As a result, disadvantaged students are placed at a disadvantage, where standardized test scores are influenced more by socioeconomic status than by actual academic potential or effort. The SAT reinforces existing inequalities, making it harder for talented students from underprivileged communities to compete fairly in the college admissions process.

The shift to test-optional policies, initially driven by the COVID-19 pandemic, offered colleges a chance to transform their admissions processes into something more holistic and innovative. Instead of seizing this opportunity to create a more equitable system, many institutions appear to be retreating to pre-pandemic practices, favoring the familiar, albeit flawed, methods over embracing meaningful change. Rather than reverting to outdated norms, colleges should use this moment to overhaul their admissions practices, making them fairer and more reflective of a student’s true potential beyond standardized test scores. This is an opportunity to redefine what it means to evaluate applicants and to build a more inclusive and just admissions system.