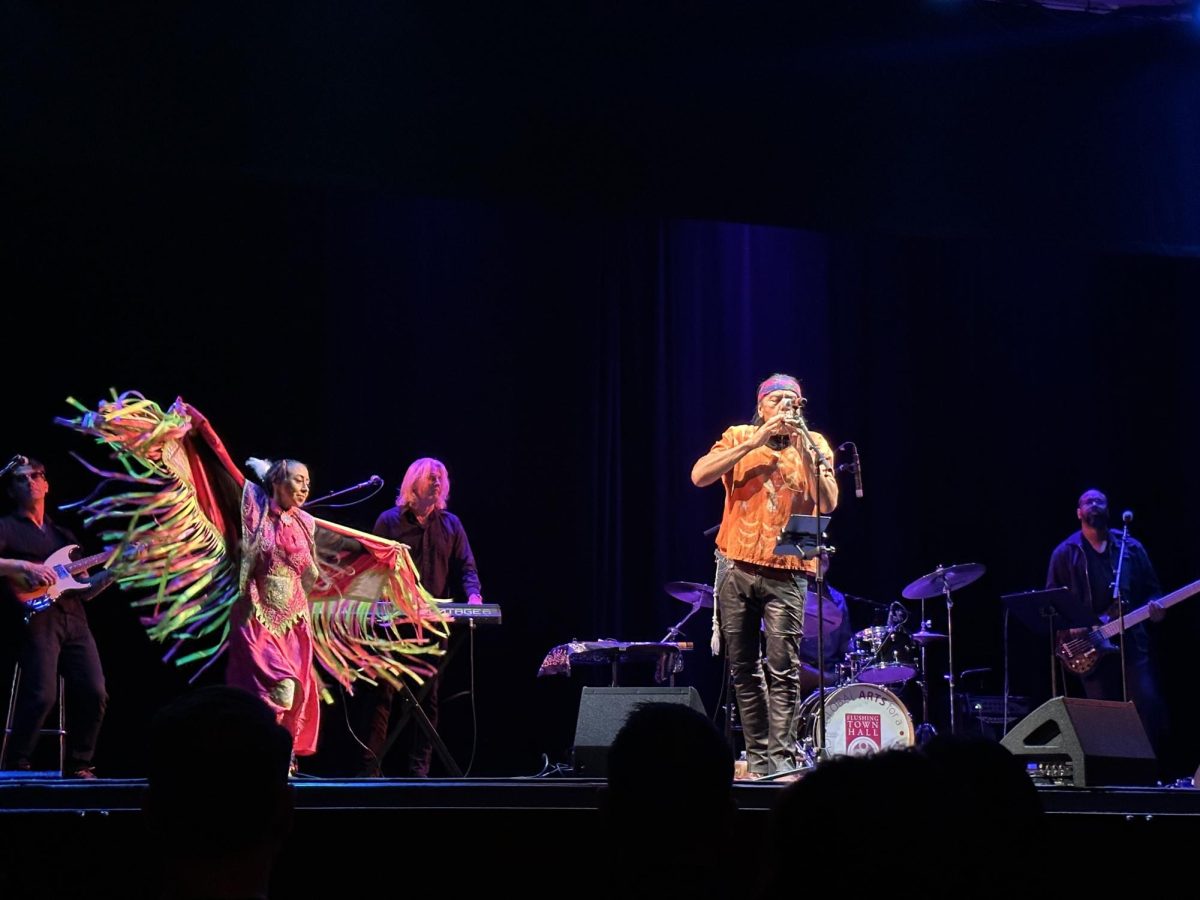

“When I close my eyes I can see the vastness of the world, the vastness of the southwest, the vastness of the song, the dance, and the rituals. They are all inside of me and tonight, you get just a little bit of the storytelling,” said Grammy award-winning musician Robert Mirabal to an audience at the Flushing Town Hall on January 31.

Mirabal and his band, Rare Tribal Mob, contributed to a night of music, dance, and discussion related to indigenous arts and culture.

At the start of each song, Mirabal captivated audience members (including reporters from The Classic’s arts & entertainment department) with personal narratives and stories to present the traditional backgrounds that embody the songs. At one point, Mirabal said that he sees his art as a way to preserve what is being forgotten.

“We are in difficult times. Not just my village but all over the world. A lot of tribal people are,” said Mirabal.

Mirabal’s story is rooted in his cultural background and desire to “storytell” through his art. Raised in Taos Pueblo, New Mexico, Mirabal’s works reflect his upbringing by combining storytelling, flute songs, and tribal rock.

The performance also featured “powwows,” derived from the Algonquian term pauau, which refers to the communal celebrations of Indigenous cultures where singing and dancing are central traditions.

Dayani Brown co-hosted a panel discussion prior to the performance. Brown, a member of the Shinnecock tribe, said, “Today’s rendition of powwows are not sacred anymore–it’s [very] different. They are [now] commercialized and that came around the early 1900s.”

Tecumseh Ceaser, an indigenous artist of Montaukett and Unkechaug descent, also hosted the discussion. He is a part of the Matinecok clan and has been creating traditional art and jewelry for over 15 years. During the discussion, Ceaser said, “It was up until 1978 that it was [considered] illegal for Native Americans to practice their culture publicly, unless we were entertaining [others]. It’s [a bit] weird because there’s that call for us to share our culture, but not that recognition of the [many] boarding schools that punished [us for] our culture.”

Caesar also stressed the importance of meaningful cultural education. He said, “Don’t treat teaching indigenous culture as something you’re trying to check off. A lot of times, you will have schools [that teach about this], and departments that do almost no research [before educating]. In order to learn history, you should go to indigenous people’s events [or] bring indigenous people to schools [to educate others].”

Similarly, Mirabal said, “Recording is useless because we need to talk to you. You can write the language down, but you can’t read it.”

Caesar adds, “[These stories] are not just something kids are reading about. All these people exist, and they can tell their own stories.”

For these indigenous artists, art is more than self-expression, it is a tool for educating others and resistance. “One person can’t do everything. It’s the community. If the community is failing, then what do you do? We need compassion to share and understand,” said Mirabal.

Correction: The original text of this article listed Barbara Collins as the co-host of the panel. Ms. Collins was originally scheduled to be at the event but was unable to attend. Dayani Brown filled in.