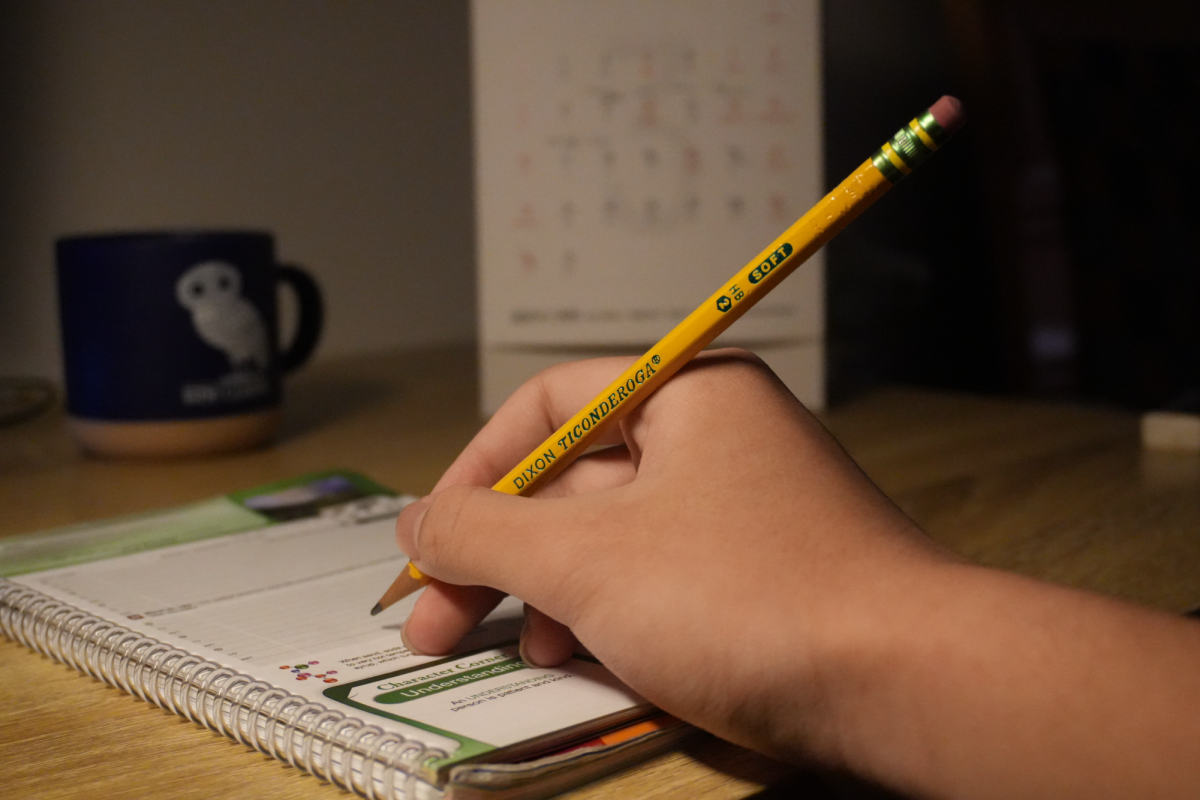

Throughout decades of major shifts in education and advancements in technology, the No. 2 pencil has remained a staple: it is practically a fashion statement, a superstar — an educational icon. And this icon’s most famous home is to be found in the standardized testing room, where most major exams have often come with one simple requirement for students: to bring a No. 2 pencil. Earlier this week, however, after all sophomores took the digital PSAT and all juniors took the digital SAT, that requirement was no more.

It’s time to wonder if the days of the No. 2 pencil’s standardized testing dominance are numbered.

It may seem like a small matter, a joke even, but it’s representative of a larger trend. The CollegeBoard is on its way to becoming fully digital. The SHSAT, the New York City Specialized High School Exam, might be next. And it’s not just standardized tests. Many teachers assign eBooks now, or no longer require other past staples on back-to-school shopping lists. There are fewer calls for five-subject spiral notebooks, fewer marble notebooks, and fewer binders. The pandemic and remote learning appears to have quickened the pace of a digital revolution in education that was on the horizon before 2020 but now is fully here. And yet, amidst all of these changes, it’s important to remember the small things — like No. 2 pencils.

The Classic asked students and teachers how they feel about this changing educational landscape and whether or not they see a future for No. 2 pencils should paper tests go extinct.

Some Townsend Harris students still see a place for No. 2 pencils, even if testing companies no longer do.

Sophomore Safir Azad said these writing instruments may still have a role in testing, even digital ones.

“Considering that most tests will be taken digitally by students, the usage and need for No. 2 pencils may decrease or change,” Safir said. “However, in some scenarios, a No. 2 pencil may be used when doing math on a separate piece of paper for a math exam.”

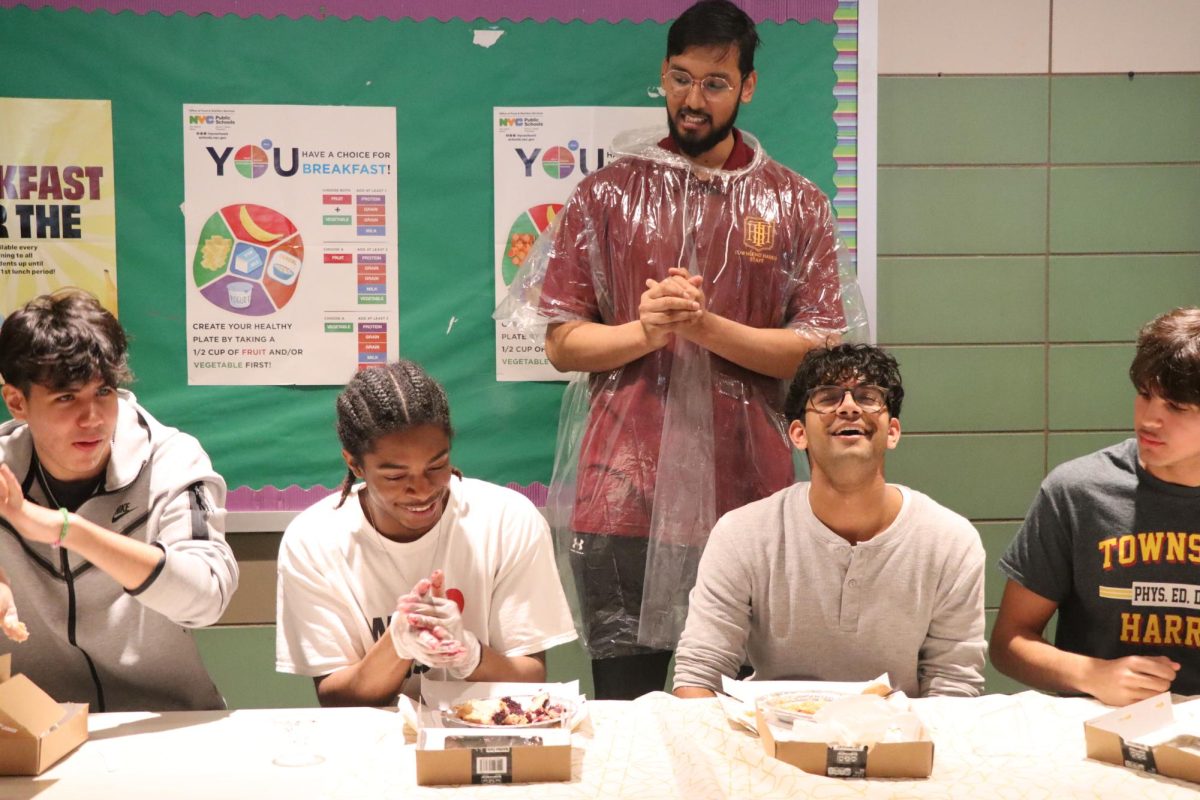

Freshman Zackary Ekwaneen, however, welcomed the coming pencil-ocalypse: “I feel indifferent to the idea of the pencil fading out because I prefer test-taking on the computer. It doesn’t waste as much paper, and it’s easier and faster for the teacher to grade.”

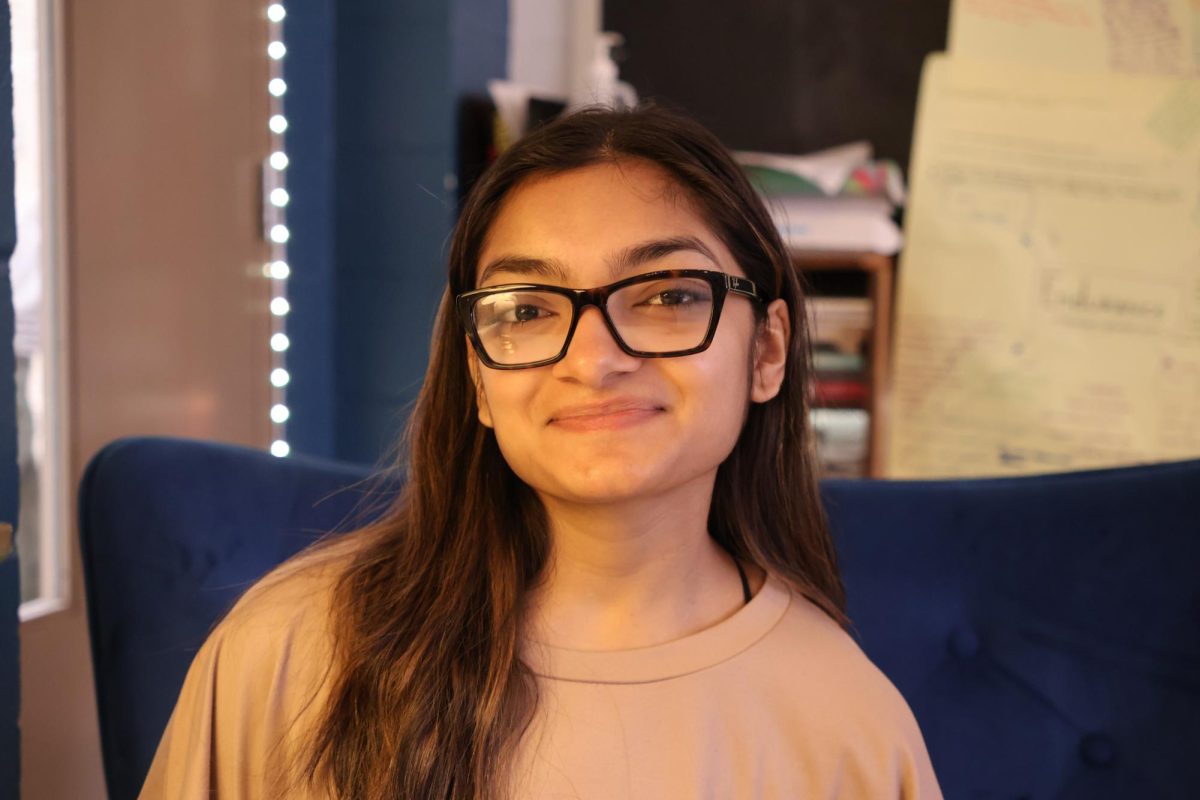

Freshman Priya Das seemed similarly indifferent: “I actually like doing things digitally. Taking tests on computers just feels quicker, and it saves paper, which is better for the environment.”

Other students, like sophomore Md Alam, were nostalgic.

“My entire academic life has been based around this pencil, and the thought of it disappearing makes me remember all the times a teacher told me to ‘Take out a No. 2 pencil,’” he said. However, he wasn’t willing to give it up just yet: “Given how essential this pencil has been to school life for decades—from bubble sheets to Scantrons—it’s intriguing to consider how its role may evolve.”

Feeling nostalgic for the No. 2 pencil makes sense, as its birth dates all the way back to 1500s Europe, when graphite sticks were first placed in wooden casings. The No. 2 part came later, when scales for different levels of graphite hardness were used to distinguish pencil types. According to Geddes, a school supplier that sells No. 2 pencils, “The hardness of graphite varies and therefore a scale is used to describe the varying levels of hardness for graphite. The number two is a mid-range graphite hardness, which makes it suitable for academic use because it makes a mark that is sufficiently dark (and therefore able to be read by scantrons) and also easy enough to erase.” Higher number pencils on the scale would hold inside them harder graphite that makes lighter but more difficult-to-erase marks.

Like students, teachers also had mixed feelings about the possible coming obsolescence of No. 2.

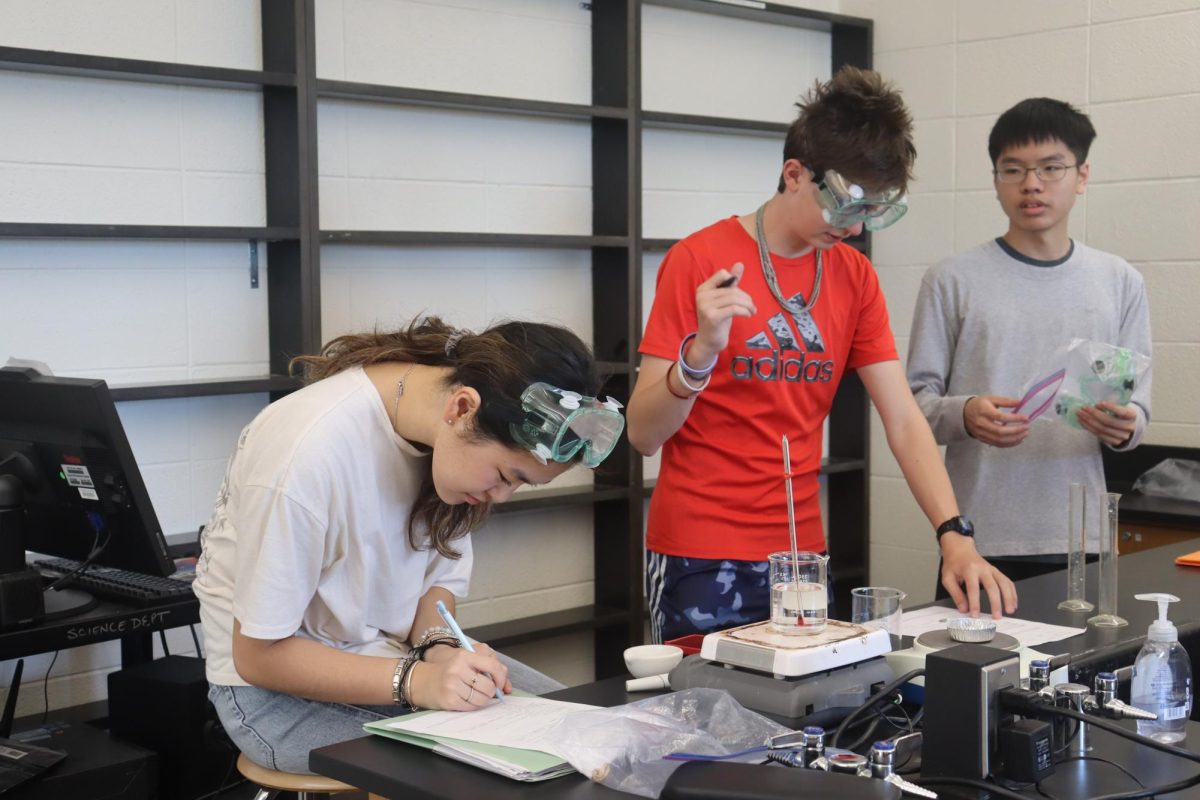

Chemistry Teacher Tanya Karcic said that fewer pencils in the classroom would “not be too impactful to the science department” and that it would “adapt easily” to the change.

“Computers are enough for science class,” Ms. Karcic said.

On the other hand, AP World History Teacher Frank Spitaleri is a strong defender of the pencil, saying it still holds value in school systems.

“The No. 2 pencil still holds a place of importance, even if it’s less so in testing,” Mr. Spitaleri said.

Mr. Spitaleri might be onto something.

According to Verified Market Research, “Pencils Market size was valued at USD 14.5 Billion in 2023 and is projected to reach USD 31.9 Billion by 2030.” In short, despite the digital testing shifts, pencil sales are projected to be on the rise. According to the study, this is due to global educational initiatives: “many developing countries have launched schemes to distribute free pencils and other school supplies to encourage enrollment and reduce the dropout rate.”

Though No. 2 pencils may no longer be so crucial once detached from standardized testing, pencils themselves appear to remain a key part of global education trends.

Mr. Spitaleri said that he was not necessarily against the growing digitization of all various aspects of education, but he said that writing things out by hand offered a valuable experience for students.

“Computers are great,” he said. “But they’re not quite there when it comes to replicating the experience of traditional methods, whether it’s showing work in math or creating art.”

In other words, using pencils, with or without standardized testing requirements, might not be so pointless.