The pounding of my heart drowns out the insistent reminder from my teacher to “keep our eyes on our own paper.” My nails dig into my palm as I scratch out yet another one of my failed attempts to answer the daunting question in front of me. An eraser scrubs off “15 minutes” on the chalkboard. Now, in its place is a new disconcerting time of “5 minutes.” I’ve poured over every study guide, textbook, and worksheet for the past week, and I’m unable to find the information to solve the three questions sitting in front of me in the scramble of my brain. This, however, does not seem to be the same for my peer adjacent to me, whose features are stress free. I sit conflicted, wishing their answers would also appear on my paper, knowing I could make it happen. My hands grow clammy, and I sit frozen, unable to accept the thought that just crossed my mind.

Although I will never give into that temptation, I remain discontent knowing it was there. After working hard to prepare for this exam, I shouldn’t feel displeased or guilty with the outcome of an assessment that is meant to accurately measure my understanding of a topic. However, this feeling of guilt is not unique to me. Why does a simple test push us into these emotions? Many students leave a test with lingering feelings of failure, temptation, and subsequent guilt. But are students the only ones solely responsible for this? I believe not. This mixture of stress is an obvious result of high-stakes testing, and the sheer amount of high-stakes tests students take in a term.

According to a study that specifically focuses on academic dishonesty in a high-achieving population (like that of THHS), “High-achieving high school students cite heavy workloads (68%) and multiple tests being scheduled on the same day (60%) as two of the top reasons that they cheat.” The researchers note that these students can usually meet their goals when considering all tasks in isolation, but “the cumulative burden [of various tasks] creates enormous stress and encourages students to seek shortcuts to accomplish all of their goals.” In their conclusions, the researchers say, “Although there is no magical solution for addressing dishonesty in this climate of winner takes all, …cheating among this group might be reduced if teachers and school administrators work to make assessment clear, fair, and consistent; model the value of learning; minimize comparisons among students; teach students prioritization and regulation skills; and communicate their empathy for high demands and worries associated with the students’ pressured lives.”

In other words, when there is demonstrated commitment that the school’s systems are fair, predictable, and built on empathy, there is more trust. This trust, however, cannot be built on a reliance on high stakes testing. There should be alternatives.

In other words, when there is demonstrated commitment that the school’s systems are fair, predictable, and built on empathy, there is more trust. This trust, however, cannot be built on a reliance on high stakes testing. There should be alternatives.

In fact, there are apparently supposed to be alternatives. According to the new testing schedule policies, “It is the philosophy of this school administration that tests are not the only way to determine if a student is learning.” Although the school may claim this to be part of its philosophy, no evident actions have been taken this semester to support this notion of providing alternative assessments.

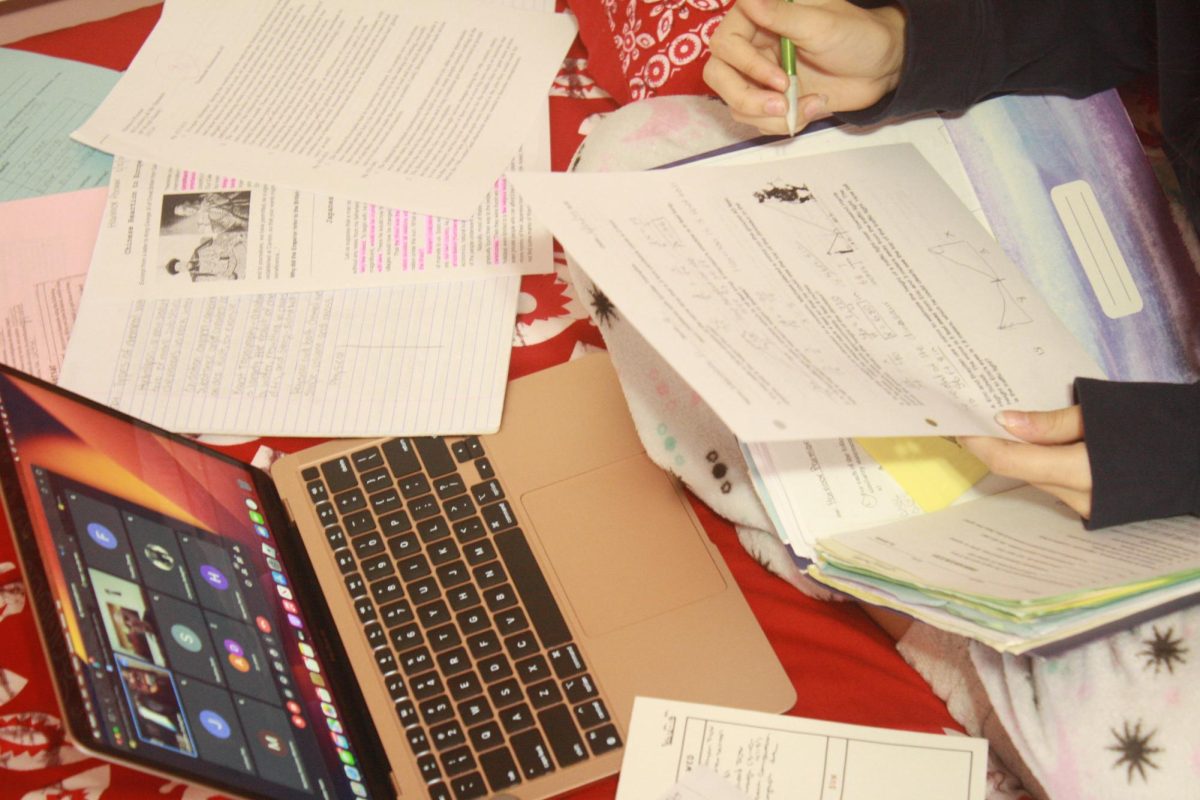

Instead, this term has been like previous terms and has been highly dependent on high-stakes testing to assess students. From my personal experience, I’ve had numerous overlapping assessments. One week, I was tested on math, science, and modern languages four out of the five days, one of which was a two-day physics test. This emphasis on high-stakes testing has begun sending the message to students that performance outweighs mastery, the very signals the study cited above that convey to students that the ends justify the means

To combat this, the school has to do more than claim that they value alternative assessments—a drastic shift to effective alternative assessments is necessary. It is easy to continue blaming students for the lack of motivation or work ethic for the reason why academic honesty has become an issue with high-stakes testing.

Alternative assessments should aim to uphold integrity between students and teachers. They should demonstrate to students that the main priority is their understanding. Effective alternative assessments should begin to re-establish a sense of faith in students that the goal of the assessments they are given are to authentically identify areas they struggle in and celebrate areas they excel in.

Consider the below example of a way to use alternative forms of assessment.

Take-home assessments can be employed for both science and mathematics classes. These assessments can emulate a high-stakes test, but the setting can reduce the associated stress. Of course, I know the first objection will be that students can easily cheat on take-home exams. However, I would propose that the assessment should not be based on just the answers but the student’s ability to explain questions that challenged them and show they learned the underlying concepts. The teacher can eliminate the issue of cheating to find just the answers by posting answer keys, power points, or other materials that aim to aid students in understanding the skills they must use in order to do the take-home assessment. The goal of these assessments would be to prioritize the explanation rather than the answer. This explanation could be written out or students could verbally explain their thought processes during a live conference with the teacher. Teachers may argue there isn’t enough time to assess all students in person in a timely manner. However, there are multiple ways for students to explain their thinking, live interviews are just one. Students may also choose to film videos of their explanations and upload them to Google classroom as their assessment or they may choose to provide written explanations instead. The possibilities are endless in today’s world where methods that students can use to demonstrate their understanding are constantly evolving.

Humanities subjects use essays as a method of getting students to reflect on and practice specific skills that they’ve been taught during a unit. These essays are allowed to be written over a period of time, with time to conference and ask questions to the teacher. This form of assessment allows students to demonstrate what they understand and have learned without the added pressure of a high-stakes test. But this method does not need to continue being limited to English classes. It may also prove to be an effective method of assessment for STEM subjects, World Languages, and Social Studies classes as well.

This is just one possible scenario, but if the school is committed to its stated philosophy, there should be many more possible solutions it can come up with to reduce the emphasis on high stakes testing. To create the kind of school culture where honesty and integrity are valued above grades and numbers on tests, emphasis must be placed on alternative methods of testing that still allow teachers to authentically assess students on their collective knowledge of a topic, and not students’ knowledge at one point in time, on a test.