Though our logo may seem ornate, the students at THHS do not have the “superiority complex” that was mentioned in Jensine Raihan’s article “Learning to respect thy neighbor.” Educators often refer to us as the some of the brightest students in the city, but that does not equate to us being pretentious brats—we do not turn up our noses and look in the other direction, nor do we have an enormous sense of entitlement. We continue to work hard everyday, and it is unfair to say that we should not be proud of the achievements we’ve made. To say that there is no separation between students academically is to ignore the qualities that make them unique; hence we cannot always view everyone as completely equal to one another.

However, despite the qualities that separate us academically, the students at THHS are far from elitist when it comes to class and race. We do not look down upon those with a lower socioeconomic class—in fact, we do not even acknowledge class. We are fully aware that the amount of money of you have in your bank account does not determine who you are as a person, nor does it determine what your capability. THHS is a fairly diverse school, one which was founded on the principle that the children of the rich and the poor could learn in an environment where their intelligence and personality determine their character, not their socioeconomic class.

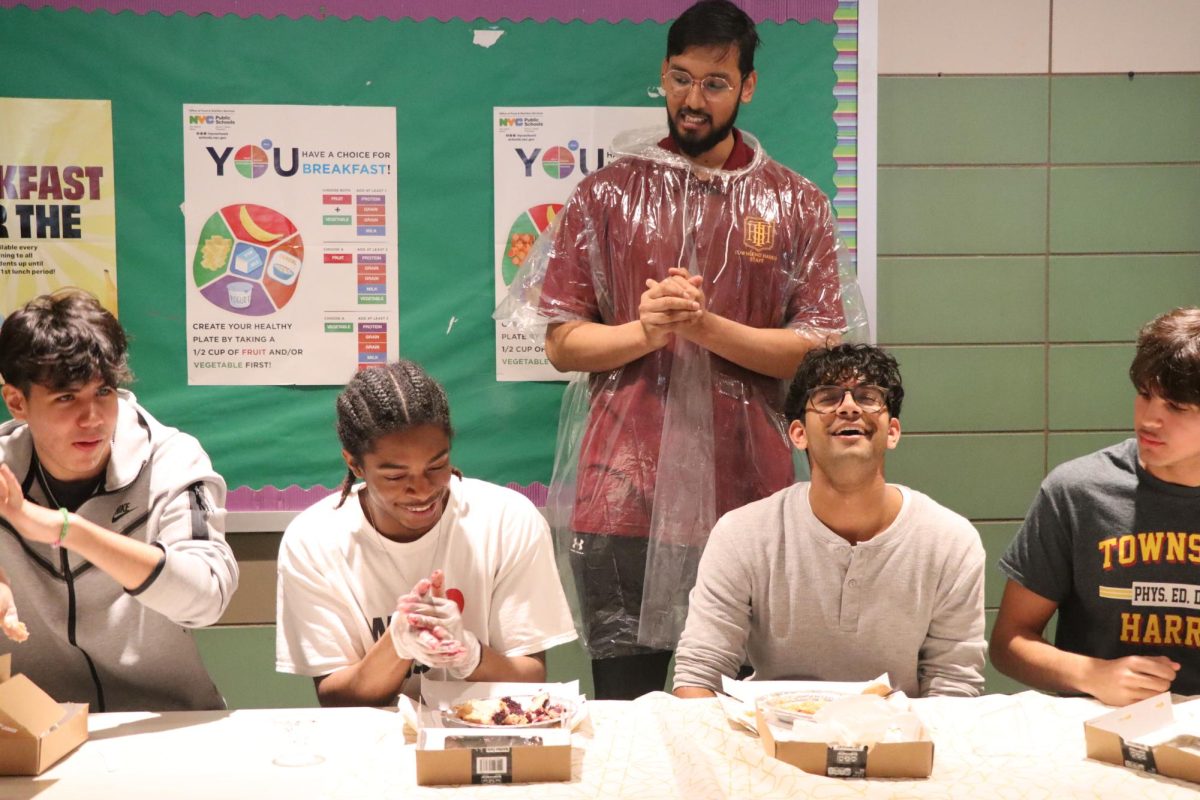

THHS is an amalgam, representing students from nations all across the globe. We take pride in the diversity that is present in the school, showcasing it in various forms including the Festival of Nations. After all, the school is situated in Queens, where immigrants from far and wide first arrive when they come to New York. As THHS students and as New Yorkers living in the 21st century, we recognize that skin color does not determine one’s potential.

Despite the fact that many of the people living in the projects are people of color with lower incomes, we do not deliberately associate crime with these people. We are fully aware that not all of the residents living in the projects are criminals and when we think to be cautious in particular neighborhoods, it is not with the intention of being racist or elitist. We have grown up in a society that has much bias in the news and media, and more often than not, we will hear of crimes taking place in less-developed areas. This does not have to do with the fact that there are several people of color living in the projects—in fact, it has nothing to do with race at all. The reputation the projects have is due to the events that are reported to occur there more often than in other areas, thus people assume a heightened sense of awareness in these places. This is not to say that we aren’t aware of our surroundings in other places, for there is no guarantee of being completely safe everywhere.

The walk that was organized against police brutality shows that we are aware of social issues and that we aren’t afraid to protest injustices when the time comes. Many other schools did not take such action, and there were many students participating in our own walk. If offered a word of caution about the protest, the concern lies more with the fact that police brutality was, and still is, a controversial topic. A walk or protest against such a subject exposes the students to other dangers unrelated to thinking that the Pomonok house residents are all criminals. Because police brutality was, and still is, a controversial topic, the students could potentially have met opposition. Even if the walk were to have been organized along a different route, the students would do well to take heed of their surroundings.

Our generation, if anything, is one of the most liberal that there has been in years. Our school offers numerous clubs that encourage diversity, and creates an environment where the students are comfortable in expressing who they are. Despite the qualities that differentiate students, we do know how to respect our neighbors.