Between the Word and Me

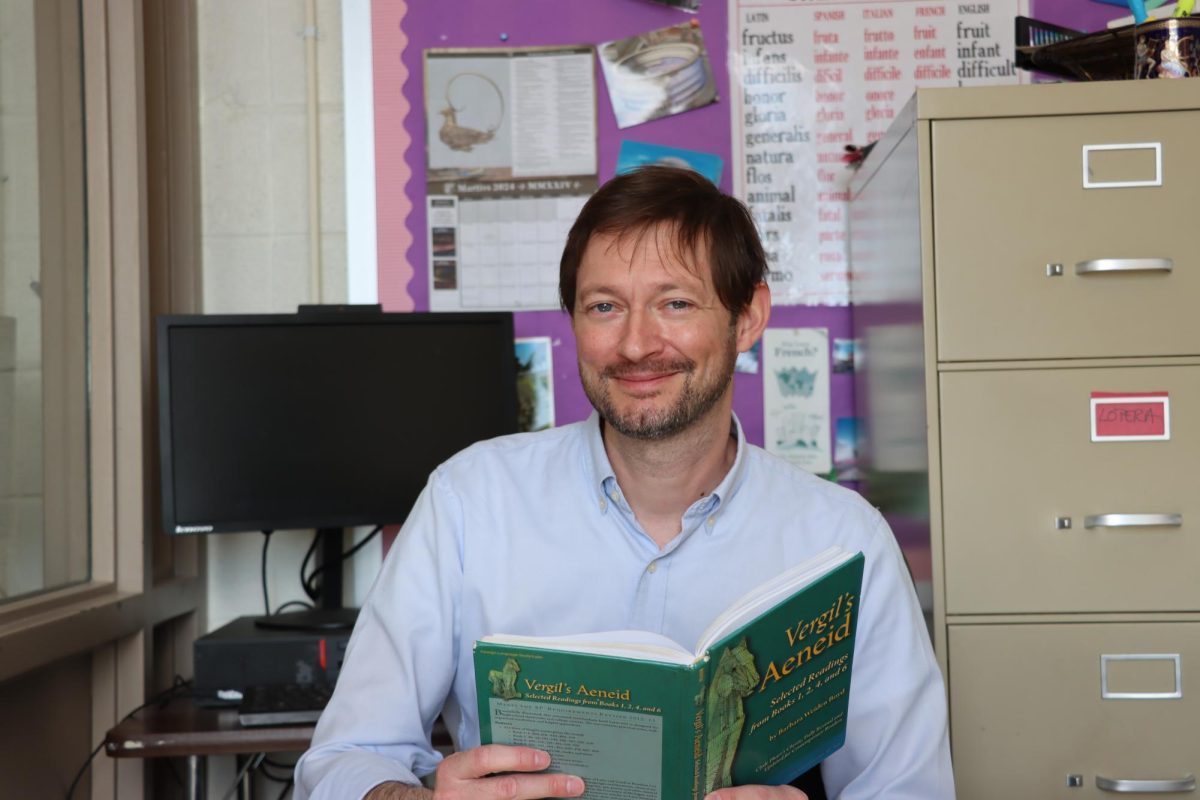

Since the publication of this article, Mr. Canzoneri was removed from Townsend Harris following allegations of sexual misconduct. Some advised that we take down this article, but since the below perspectives might be an important artifact for anyone in the future wanting to research what happened at THHS, we have decided to leave the article up with this disclaimer. You can read about the allegations that came to light and the fallout from them here and here.

Written

Wednesday, February 24th, 2016. Forest Hills H.S. Auditorium. 4:30PM:

“That covers it, boys. Make sure your paperwork is updated, and I’ll see you on March 1st for baseball tryouts. Questions? Returning players: anything the new guys need to know?”

“Yeah- be on time for practice and don’t ever say n***a. Coach Canzo will flip if you do!”

Good. It’s sinking in…

I think I’m a pretty tolerant guy. I don’t have a lengthy list of do’s and don’ts in my classroom. However, like Nick Carraway, I must admit that my tolerance has a limit. Certain things set me off. Hearing teenagers say “n****r” or “n***a”—I’m less inclined to separate the two than most—is one of them. When we study Huck Finn—a novel that uses the word “n****r” over two hundred times—I deal with the word directly. I say it aloud. Frequently. We watch a documentary on the word’s history. We ask who—if anyone—owns the word. We consider the alleged evolution of the word, and we wonder about the attempts by many to eradicate the word’s original meaning and refashion it into something entirely new. Can words evolve or do they merely acquire additional layers of meaning? You can drop the “-er,” add an “-a” and hug and high five one another while saying, “Sup, n***a?” but you can’t change history.

I can direct you to several essays written by intelligent black men and women who argue that “n***a” is a beautiful, inoffensive expression of brotherhood, camaraderie and love. Ta-Nehisi Coates, whose brilliant Between the World and Me should be required reading, is one such man. He argues that the word’s use shouldn’t be limited because doing so is another way in which the white race oppresses its black counterparts by playing judge and jury in the matter of dignified, respectable speech. I see his point. However, he also admits that, “If you could choose one word to represent the centuries of bondage, the decades of terrorism, the long days of mass rape, the totality of white violence that birthed the black race in America, it would be ‘n****r.’” There’s an epithet for every race in America; none of them stings quite like “the ‘n’ word.” In fact, none are censored and quarantined in quotation marks like “the ‘n’ word.” Shouldn’t that lead an educated person to conclude the word hasn’t really evolved at all?

It doesn’t bother me to hear “n***a” in rap music or in films. Those are art forms, and artists need all-access passes to language in order to express themselves truthfully. However, the word sounds crude and classless when a teen uses it, and it sounds strange to me when I hear it out of the mouth of someone who isn’t African-American. I want to say, “Do you have any idea how ridiculous you sound? How fake. How look at how hard I’m trying to be street?” I am surprised and saddened by the regularity with which Harrisites admit to using the word in conversation and on social media.

What concerns me when I hear teenagers use the word today is that I fear they’re oblivious to history: not slave history, but recent history. I think some teens associate “n****r” with “the slave days” or “the 1800s.” Even though students learn about the Civil Rights Movement in middle school, I wonder if they’re aware of the horrific ways black men and women were treated in this country fifty years ago. I wonder if they’re aware of the inequalities that still persist today.

Michael Rappaport, a Caucasian actor who is featured in The N Word, a documentary I show in class, argues that “n***a” means the same thing as man, dog, homie, homeboy, pimp and playa: “It’s a list; you just pick one,” he explains. I don’t see it that way at all. “N***a” knows no parallel; it has no synonym. One of my students, junior Christine Lee, said, “If all those words mean the same thing, why not use one of the other ones which won’t hurt anybody and doesn’t have that awful history?” Bravo, Ms. Lee. Gold star!

Baseball season commences March 1st. My pitchers will struggle with their command, my hitters will struggle with their bunting techniques and all will commit errors, with their gloves and their mouths. “N***a” will slip out. It happened this afternoon, after I’d dismissed the new players and spent some time with my veterans. “Sorry coach, my bad,” the offender said, after he’d realized his transgression. Good. It’s sinking in.

December, 2016. THHS. Room 404: Current sophomores, get ready…

Your donation will support the student journalists of The Classic. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment, support our extracurricular events, celebrate our staff, print the paper periodically, and cover our annual website hosting costs.