THE RED paint is peeling. The brakes are out of order. But until he buys himself a Raleigh mountain bike in college years later, the ‘80s Schwinn is sixteen-year-old Rafal Olechowski’s most viable mode of transportation.

“It wasn’t as if I could get myself a driver’s license,” he says.

Assistant Principal of Humanities Mr. Olechowski has been a legal citizen of the United States for most of his adult life, but his late adolescent years are largely shadowed by the restrictions he experienced as an undocumented teenager. Immigrating from the small town of Sierpc, Poland just shy of his sixteenth birthday, Mr. Olechowski moved to Rego Park with his sister and her husband, attending Forest Hills High School as a ninth grade ESL student, a year behind peers his age.

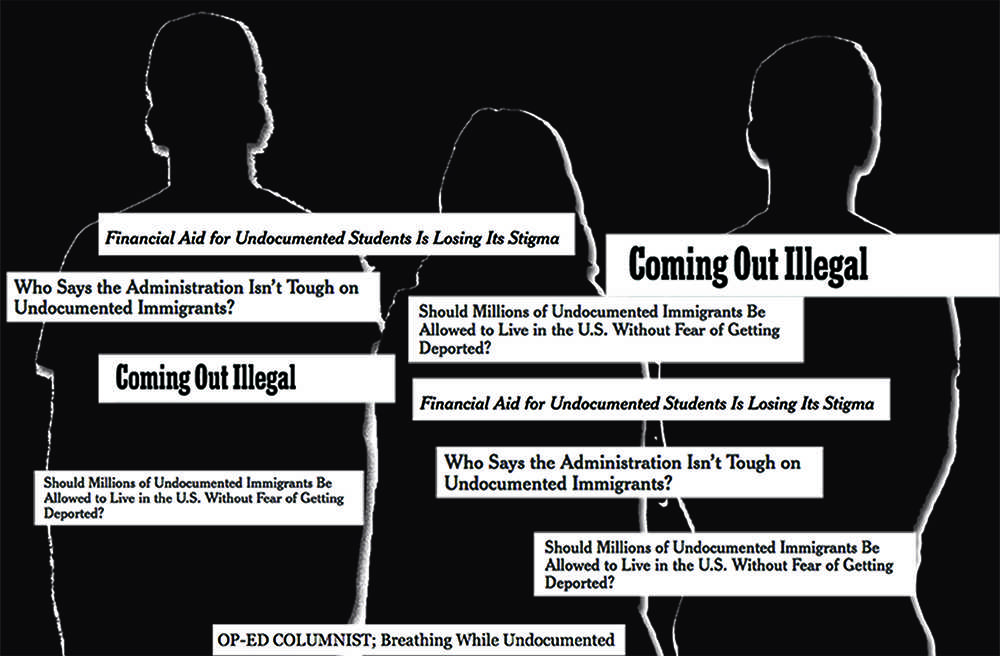

“I lived [each] day not knowing what would happen [the next]… I was filled with constant anxiety about being found out. I’d wake up in the middle of the night disoriented, in my head going through all the places I could possibly be―Queens? Poland? A detention center? Without papers, I could get arrested at any moment.”

The National Immigration Law Center defines undocumented citizens as foreign nationals who “enter the U.S. without inspection, fraudulent documents, or legally as nonimmigrants who violate the terms of their statuses by letting their Visas expire.” Mr. Olechowski entered school as a foreign student (F-1), which meant that his student Visa expired after a year. After the twelve-month period elapsed, he remained; his legal residency did not.

THE EVERYDAY PROBLEMS IN AN EDUCATIONAL ENVIRONMENT

For undocumented students, daily school life can be a minefield: although the 1982 Plyer v. Doe decision means that schools must provide an equal education to documented and undocumented K-12 students (the provision of Social Security number forbidden as a prerequisite for enrollment, and a child’s immigration status given protection from individuals, institutions, and even other government agencies), students still operate relatively low-profile, given the constant threat of deportation.

Basic tokens of citizenship that manifest throughout adolescence—a driver’s license, a bank account—are experiences from which undocumented immigrants are largely isolated. “I can’t leave the country or travel,” said an anonymous undocumented Townsend Harris student. “I can’t enter one contest or another, have little hope of ever owning a car or a house, and feel excluded from everyone, pretending that I’ll be able to vote someday when my friends talk about politics and their future goals… I don’t really have much hope for the future.”

“I’m always reminded that I don’t fit in,” one student offered.

Securing employment proves to be a particularly pressing issue among undocumented students; this isn’t surprising, given that one-third of the children of undocumented immigrants and a fifth of adult undocumented immigrants live in poverty, as a 2007 study by the Pew Research Center finds. This is nearly double the poverty rate for children of U.S.-born parents (18%) or for U.S.-born adults (10%).

“I can’t get working papers even though I’m old enough, so I can’t get out of what is a difficult economic situation for me and my family,” said another undocumented student. “It’s hard to find a job without them.”

“[In high school], I hopped around from odd job to odd job,” said Mr. Olechowski. “They were all off-the-books, as they had to be… someone at a butcher shop might recommend me to someone at a luncheonette, and that’s how I would stay employed… they weren’t very good jobs. The work that I could get was demoralizing, the kind of jobs children that age have no business being made to do.”

Rishi Singh, Director of Youth Organization at Desis Rising Up and Moving (DRUM), a community-based activist organization working for social and policy change affecting the rights of South Asian Americans, immigrated undocumented from Trinidad to New York City in 1999, when he was ten-years-old. “As a result [of unreported employment], undocumented folks are often taken advantage of or exploited,” he said. “I used to do jobs that didn’t pay minimum wage—that’s what people like us have to do to survive. There are so many people in our community from retail to domestic workers that are treated unfairly because of their immigration statuses.”

Even the most quotidian of school activities can introduce difficulties. As Assistant Principal of Organization Ms. Ellen Fee describes, “even if you’re undocumented [and not] struggling for money, financial payments can pose problems… things like paying for senior dues or for junior banquet must be done in cash as opposed to checks… Say you were the one that got the chinese ribbons for Festival of Nations. The school can only [reimburse] you in checks but you can’t cash those if you don’t have an account. Checking places take money from you. Some students use their friends’ parents to cash checks, but that involves awkward questions.”

Proxies as a method of making basic monetary transactions are a common trend among undocumented students. The SATs are payable by credit card, PayPal, check, or money order, the final of which doesn’t require a bank account. As one student said, however, undocumented families don’t necessarily need to resort to that. “We know people who know people who give us debit cards.”

“Being undocumented in high school presented a lot of problems with motivation when it came to schoolwork, especially during my critical junior year,” said Dennise Hernandez, Class of 2013 alumna. “At my worst, I couldn’t really see the point in working so hard on my academics if there was the very high possibility that it might not pay off not because I didn’t ‘work hard enough’ but because of circumstances that were entirely outside of my control. In retrospect, I recognize that I experienced a form of depression at the time, but I didn’t have the emotional vocabulary to identify it as such back then.”

She added, “Being at an academically-intensive place like THHS also presented its own difficulties…it magnified my legal status for me. Every year The Classic publishes a feature on where all of the graduating seniors will be going to college. Not a single name draws a blank next to it, but as early as my freshman year I used to wonder what would happen if my name would ever have a college listed next to it. In an educational culture where the question is not ‘will you go to college’ but rather ‘where will you go to college,’ the possibility of not reaching that standard was terrifying. As a result I experienced a lot of self doubt and a feeling that nothing I achieved or accomplished would ever be enough to ‘earn’ what I most needed which was documentation.”

SOCIAL INSECURITY: THE QUESTION OF COLLEGE AND PAYING FOR IT

For undocumented students, however, the problem only begins with primary and secondary education, given that the road tends to end beyond that; a College Board report finds that of an estimated 607,000 undocumented K-12 students in the country, only 65,000 graduate, and that only five to ten percent of that number attend college after graduating high school.

Although colleges don’t generally ask for proof of documentation such as a Social Security number, an SSN is required for processing financial aid forms such as the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), which is often the deciding factor for students in the admissions process. It’s make or break, usually the latter in the case of undocumented students.

Almost all private colleges and universities classify undocumented students as international students, considering their financial situations when determining admissions.

Undocumented students in this instance compete with students from throughout the world for a handful of enrollment slots; an undocumented student’s ability to fund his or her entire four years of college is considered in admissions decisions. Because of these policies, thousands of qualified and competitive undocumented students are denied admission to private colleges every year.

“The problem is, they’re not entitled to state or federal financial aid,” said Principal Anthony Barbetta. “The issue, beyond getting into college, is dealing with the cost of it without help.”

Dennise, who immigrated from Mexico, is currently matriculated at Dartmouth College. Despite that eventual destination, however, that path wasn’t always paved with ivy.

“The most difficulty I had was in trying to figure out how to finance my education,” she said. The Questbridge scholarship program was what allowed her to apply to many selective schools for free. “I knew that my legal status would limit me from being able to apply for federal aid, and that I wouldn’t be able to apply for loans, so I looked to scholarships… four years ago, I found that I couldn’t apply to about 97% of the scholarships I came across. Many scholarship-granting organizations have changed their application procedures in recent years… I remember [not being able to] apply to the Gates Millennium scholarship program and being angry and frustrated even though I was a competitive applicant.

“After disclosing my status to my guidance counselor, she offered to reach out to institutions for me and find out [if they were] ‘undocu-friendly’… I [took] it upon myself to [write] to dozens of schools, disclosing my status and asking about how my process would be different. Many schools told me that they could not consider my application, or that I would be considered an international applicant. Most notably, they told me they would not be able to offer me grants or financial aid because of my status. It was disheartening, to say the least.”

“Whether people like it or not, this country is our home too, and we should be able to afford an education,” one undocumented student concluded.

A 2001 New York State law expanded on who can qualify for in-state tuition; that is not the case with most states.

CUNY and SUNY are among the collegiate systems that fall under this umbrella. As Rishi, who attended Hunter College commented, “I had to put it on paper first, saying that I was undocumented, even if I didn’t need an SSN… there was [visibility] there.”

THE GREEN CARD RED LIGHT: APPLYING FOR CITIZENSHIP

Since 2012, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) has allowed certain undocumented immigrants who enter the country before their 16th birthdays and before June 2010 to receive a renewable two-year work permit and exemption from deportation, permitting many undocumented immigrants to come out of anonymity.

Stephanie Park, Representative and Community Fellow of Immigrant Justice Corps at the MinKwon Center, a Flushing-based organization representing the Korean-American community, commented, “DACA status does not give documented status… [despite allowances], DACA still means undocumented.”

“Receiving my Social Security and work permit was surreal,” commented Dennise, who acquired DACA status in 2012. “My work permit allowed me to gain employment, get paid, and receive my driver’s permit. I should’ve had access to these things from the ages of 14 to 16, and after waiting years it felt like a weight had been lifted.”

As Guidance Counselor Sara Skoda noted, “a lot of these students are eligible for DACA status and don’t realize it… they should seek assistance from guidance. We’re here to help.”

One current undocumented THHS student is warier of DACA status. “It’s implemented under Executive Orders, so it’s up to the discretion of [whomever] is president to make sure we have rights… it provides kids two years of protection from deportation, working authorization, and an SSN, then a [bi-annual] renewal process, but what about my parents? I still worry about them getting deported, and being left behind.”

“The DREAM Act is great,” he commented. “Well it [would] be. In just six years, you’ll be able to become a citizen.”

The DREAM Act (Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors), is an oft-discussed legislative proposal for a multi-phase process to grant conditional residency to undocumented immigrants, and upon meeting other qualifications, permanent residency; though introduced to the Senate in 2001, and reintroduced several times since, it has consistently failed to pass. Proposed requirements for conditional residential status include garnering a high school degree or GED, demonstrating “good moral character” and passing criminal background checks; proposed requirements for permanent residential status include attending an institution of higher learning or serving in the United States military.

“I think [the DREAM Act] is interesting because it grants opportunities…in a bigger picture sense, however, I question its full efficiency. I feel like it’s kind of a cop-out that tokenizes “good-acting” immigrants, for those who meet all these sort of checkpoints that say you are worth it and tell other people that they aren’t,” commented Aquib Yacoob, Class of 2011 alumnus and Executive Special Projects Coordinator at Amnesty International USA. “If you look at people in poor communities with little access to resources, getting a [certain level] of education or employment to qualify under the act is improbable.”

Even upon acquiring a green card, there still exist nuanced but notable differences in daily life from other citizens.

Though Dennise later transitioned from DACA status to having a green card, she commented that “[she] does not feel fully integrated into American society…despite the critical changes to [her] documentation.”

“I am frustrated at my inability to vote,” she said. “I will never get to vote in New Hampshire where my vote is worth more than it would be in New York… I won’t be able to vote at all until 2020.”

One current student comments, “being undocumented is not a choice. Students like me were brought here young by our parents, who simply wanted better lives for their children.”

As Ms. Skoda comments, there is some hope. “It’s slow progress, but there are increasing opportunities [outside the realm] of legal status. At the end of last month, the New York State Board of Regents passed a rule allowing certain undocumented immigrants who immigrated as children to apply for professional teaching certificates in 57 professions, including nursing and social work.

On advice he would give to current undocumented students, Rishi said, “the only way to change things is to stand up and do something… nobody is going to do something for you.”

“Coming to reclaim your identity and break away from the narrative of illegality [perpetuated] by politicians [might] take [you] years… [students] should remember there is no one way to be ‘successful,’ and that there is strength in vulnerability,” offered Dennise.

“Form strong bonds with your friends and your family,” Mr. Olechowski concluded. As an afterthought, he added, “and get yourself a bicycle.”

Karen Lin • Oct 15, 2016 at 12:09 am

Superb article on an important issue that is not often addressed.

Well-researched and thoughtfully written.