Hamilton movie does not throw away its shot

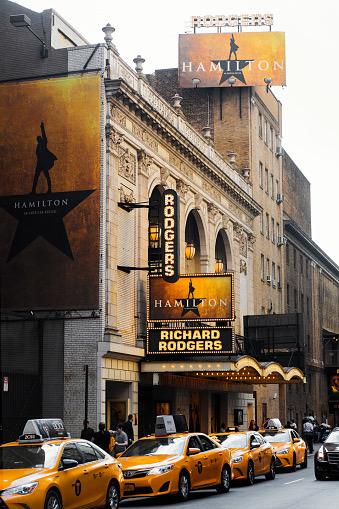

New York, United States – October 17, 2016: Richard Rodgers Theatre Hosting the Hamilton Musical – The Richard Rodgers Theatre opened in 1924 and, originally called the 46th Street Theatre, it was renamed in 1990 to honor the legendary composer Richard Rodgers, whose shows defined Broadway for over three decades.

Time to rise up and get your TV remote— Hamilton has officially made its way to Disney+.

Unlike movies whose movie theater release dates were pushed back by up to a year due to the coronavirus pandemic, Disney had moved up the release of Hamilton on Disney+ from October of next year to July 3.

The availability of Hamilton on the streaming service comes nearly five years after the hip-hop musical made its Broadway debut at the Richard Rodgers Theatre, and it appears to have come just in time during the ongoing fight for social justice in America.

Within the first thirty seconds of having hit the play button, fans can easily recognize the beginning melody from “Ten Duel Commandments” and “The World Was Wide Enough,” which is then followed by a round of applause from an audience at a performance of Hamilton from June of 2016. Once King George, portrayed by Jonathan Groff, provides a pre-show announcement, viewers immediately feel like one of the 1,319 audience members at the original performance.

The film is eloquently put together from footage of three performances. In an interview with Good Morning America, creator of Hamilton Lin-Manuel Miranda revealed that the “Hamilfilm” was pieced together from three separate performances, including one on the production’s dark day. Despite this being the case, director and producer Thomas Kail made it seamless.

The first act of the musical depicts the journey that Alexander Hamilton takes after arriving in New York from the Caribbean island of Nevis. The eager 19-year-old declares that he wants to “rise up” in the third musical number after being introduced to John Laurens (Anthony Ramos), Hercules Mulligan (Okieriete Onaodowan), and Marquis de Lafayette (Daveed Diggs).

With the widely applauded “Immigrants, we get the job done” line from “Yorktown (The World Turned Upside Down)” coming twenty numbers into Act I, Hamilton embodies the American dream that hard work and commitment pays off. He embraces his own personal ambitions as he follows the desire for independence. Lin-Manuel Miranda puts this into words, both as a writer and a performer: “Hey yo, I’m just like my country, I’m young, scrappy and hungry, and I’m not throwing away my shot.”

Unlike Hamilton, Aaron Burr (Leslie Odom Jr.) decides to “Wait For It,” and shows no commitment to any ideals throughout the entirety of the show. Leslie Odom Jr. does a great job at showing early signs of envy towards Hamilton, especially in “Aaron Burr, Sir” when Hamilton first meets Burr and proceeds to challenge him, asking, “If you stand for nothing, Burr, what’ll you fall for?”

As the show progresses, we see Hamilton fall in love with Elizabeth Schuyler (Phillipa Soo), get closer with his fellow revolutionaries, and gain connections, especially with George Washington (Christopher Jackson).

The first act also includes “You’ll Be Back,” a song featuring King George. In Hamilton: the Revolution, Miranda writes that when writing the musical, he “wanted to write a breakup letter from King George to the colonies,” and added that Hugh Laurie gave him the inspiration for the title of the song. Jonathan Groff sings nearly effortlessly, and convincingly portrays King George as he gradually goes mad throughout his three numbers that address the colonies. Comic relief is added here and there with pouts, yelling, and his cameo in “The Reynolds Pamphlet” in Act II.

The musical’s second act takes a turn for the worst if you’re Alexander Hamilton. Otherwise, the show is exceptional. The second act begins after “Dear Theodosia” and “Non-Stop,” after Philip Hamilton is born and after Alexander begins practicing law and is appointed secretary of the Treasury under the administration of President George Washington.

An internal struggle is shown within Hamilton as he becomes what is referred to as a “workaholic” nowadays, as he pushes away his family and becomes busy with getting his debt plan through congress. After the first of two cabinet battles, Eliza and her sister Angelica (Renée Elise Goldsberry) attempt to convince Hamilton to spend the summer upstate with his family, but he refuses.

It is here where everything begins to go South (again, only if you’re Alexander Hamilton). While the Hamilton residence remains empty, he has an affair with Maria Reynolds (Jasmine Cephas Jones). Her husband, James Reynolds (Sydney James Harcourt), writes extortion letters to Hamilton after finding out about the affair.

After James Madison (Okieriete Onaodowan), Thomas Jefferson (Daveed Diggs), and Aaron Burr confront our protagonist and accuse him of embezzlement of Treasury funds, he explains that he paid Mr. Reynolds with his own money. Not knowing what else to do, he tries to clear his name by publishing the letters himself, and reactions are shown in “The Reynolds Pamphlet.”

The Reynolds Pamphlet destroys his political career and the peace within his family. Still, his morals regarding his job were left intact. In response to the Reynolds Pamphlet, Eliza burns all of the letters that Hamilton ever wrote to her in an emotion-evoking performance of “Burn.”

This, however, is put to the side when Philip Hamilton participates in a duel with George Eacker (Ephraim Sykes). He tells Alexander before heading out to the dueling grounds in New Jersey and is instructed to aim at the sky because Eliza “can’t take another heartbreak.” Lin-Manuel Miranda writes this in a way that puts us in Hamilton’s shoes; Eliza had recently lost her sister, Peggy, and this came after the Reynolds scandal.

While the heartbreak he was thinking of would be Philip having the blood of George Eacker on his hands, it wound up being Philip’s death after he was fatally shot by Eacker. Eliza and Alexander mourn the death of their son and move uptown. Throughout the songs that cover Philip’s death, Lin-Manuel Miranda and Phillipa Soo are excellent at convincingly conveying the emotion that comes with losing a child, especially when they are at Philip’s side near the end of “Stay Alive (Reprise).”

A few years later— or rather a few songs later—Hamilton is asked to choose between voting either Jefferson or Burr for president. The two candidates figure that Hamilton’s support could get more voters on their side, and “The Election of 1800” does an amazing job at showing their mindsets when campaigning, with one of Burr’s lines being his mantra: “Don’t let ‘em know what you’re against or what you’re for.”

Because of Burr’s inconsistency, Hamilton decides to support Jefferson despite their conflicts near the beginning of the second act. This angers Burr, and Leslie Odom Jr. shows this perfectly in “Your Obedient Servant,” where he angrily utters the repeated usual “how does” opening verse. In this song, Burr challenged Hamilton to a duel at Weehawken. He also does a good job at portraying his anger in “The World Was Wide Enough” before Hamilton dies in a way similar to Philip—short while aiming a pistol at the sky.

The whole musical comes to an end with “Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story,” where different characters’ end perspectives toward Hamilton are shown, as well as what Eliza did after Alexander’s death, which included founding an orphanage and preserving his story along with the stories of Washington, Mulligan, Lafayette, and Laurens. The last line, “Who tells your story,” parallels Lin-Manuel Miranda’s other hit musical, In the Heights, as one of the protagonist’s lines in the finale of the latter is “Abuela I’m sorry, but I ain’t goin’ back because I’m telling your story.”

This song shows the ongoing theme of leaving a legacy, and while it has become the subject of much debate, many fans believe that Eliza’s final gasp at the end to be an attempt on Miranda’s behalf to break the fourth wall as she takes a look at the audience—she was successful at keeping her husband’s story alive, and there is a crowd full of people who are interested in hearing it.

In the end, the so-called “Hamilfilm” gives people the opportunity to have the best seats in the house while—ironically— in their house. If you previously watched it at the Richard Rodgers Theatre, you can relive the experience of a lifetime. While the musical does bring audiences back to the late 1700s, it also brings them back to the late 2010s, where theaters were once allowed to experience a musical at full capacity.

Your donation will support the student journalists of The Classic. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment, support our extracurricular events, celebrate our staff, print the paper periodically, and cover our annual website hosting costs.