Last month, in response to Governor Kathy Hochul’s recent law making New York one of the latest states in the nation to implement statewide smartphone restrictions in schools, the Townsend Harris High School administration emailed digital forms to community members, inviting them to share their thoughts and suggestions on how best to implement the new requirements this coming fall. The move reflects a broader shift toward reducing screen time in educational environments.

Backed by $13.5 million in state funding for storage solutions such as locked pouches (depending on choices made by different schools), the policy has received strong support from some teachers and faculty members. AP U.S. History and AP Seminar teacher Francis McCaughey said, “Mentally, I can’t worry about the phones all the time, because I have all this work I need to get done.” He added, “I do believe this policy will increase focus.”

Mathematics teacher Alice Brea said, “It’s just too easy to be distracted with the cell phones, so I’m hoping the policy will implement a full ban.”

“We’d like to see increased engagement and attendance in the classroom,” said Assistant Principal of Instructional Support Services Alana Rice. She added that limiting phone use could also encourage more face-to-face interaction among students, strengthening social connections during the school day.

The Classic asked students what they use their phones for during the school day.

Sophomore Raniel Pasaoa said, “During the school day, I use my phone to take pictures of notes, in case I’m sitting in the back of class, and I can’t see.”

Freshman Sayuri Nozaki said, “We need phones or our devices to complete assignments.”

“I check emails from my gym teacher on Jupiter or Google Classroom to see if we’ll be inside or outside for class,” said freshman Avery Chung. “I also use it in the hallways during passing periods to do some last-minute studying before a test.”

“Although I watch Instagram and play a lot of Crossy Road, I also use my phone to look at a lot of emails and check Google Classroom,” said sophomore Fiona Chan.

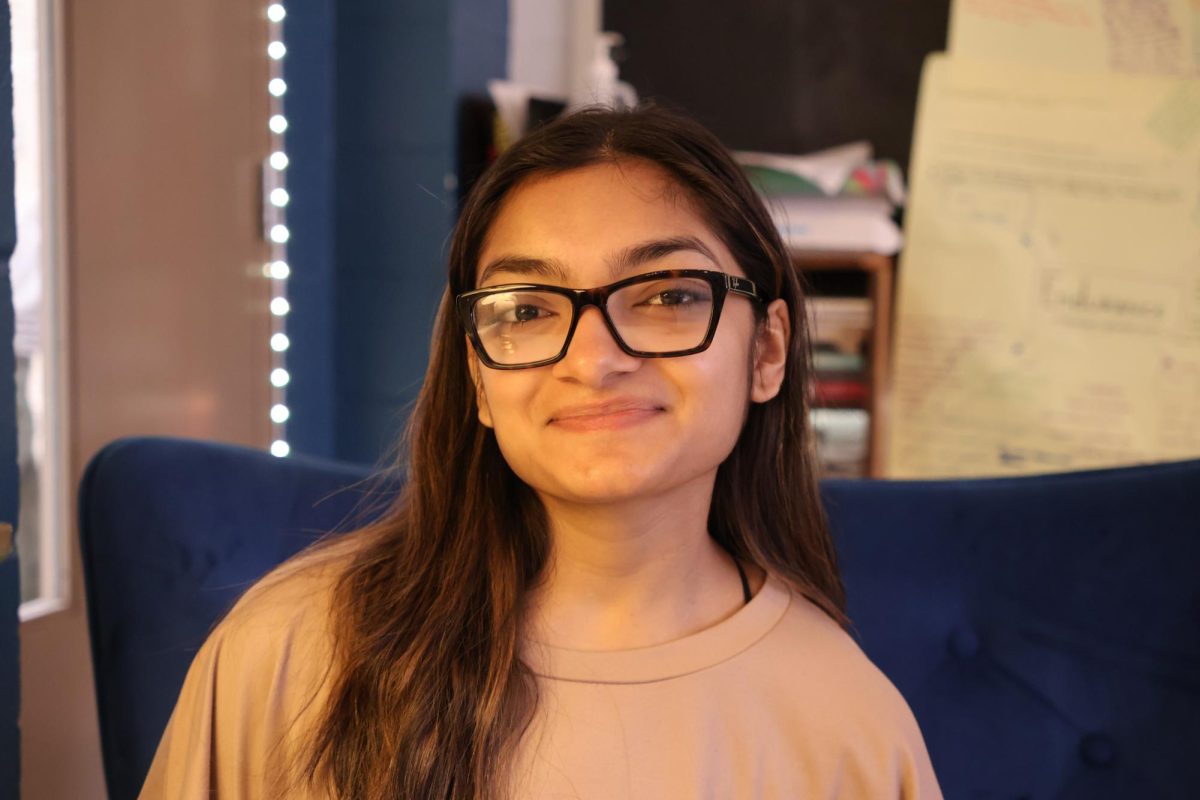

Student responses to the potential effectiveness of the new policy were mixed but mostly critical.

“Honestly, students barely use their phones in class from what I see. We normally tend to use our laptops. Their attention span could still be taken away by talking to their friends in class,” said sophomore Briana Inamagua.

Sophomore Victoria Ng said that instead of listening in class, “students will be more focused on finding ways to secretly use their phones.”

Sophomore Zafir Alam told The Classic that he had to follow a strict phone policy in his middle school. “At first I didn’t really see any use for it, but later it did help us focus more. We had Yondr pouches, but people found ways to break them, which created more distractions,” he said.

Similarly, Raniel said that although he believes restricting phone usage will help students concentrate better in class, it would also “cause students to find ways to sneak devices like their laptops, iPads, or Apple Watches into places like the bathroom.”

However, there are some exceptions to the policy. According to New York State Education Law § 2-d, the policy may still allow students to use their devices in specific situations, including health needs, emergencies, translation, or if approved for caregiving responsibilities. It also cannot restrict device use if it’s part of a student’s IEP or an accommodation plan.

Sophomore Hitarthi Bhat said, “If there’s a school shooting, I would need a phone to call the police, or if I’m really sick, I would need to call my mom.”

Parent Coordinator Jodie Lasoff also noted that many parents were concerned about reaching their children during an urgent situation.

Governor Hochul’s bell-to-bell implementation guide suggests providing a designated space where cell phones can be used in emergencies. It argues that students may actually be safer in phone-free settings during a crisis, as their full attention would be on following directions from trained teachers or administrators.

Similarly, Assistant Principal of World Languages and Social Studies Rafal Olechowski acknowledged the importance of students being able to contact their families but emphasized that communication can also happen through the school itself. “You can’t leave school without informing the school anyway,” he said.

Ms. Brea emphasized the need for support from deans and the administration to determine what consequences are necessary if cell phones are seen. However, she explained that decisions about whether and how to confiscate phones in class have not yet been made.

When interviewed in early June, Mr. Olechowski said that the policy is still unclear among the administration. “Honestly, we have to sit down as a cabinet and really think this through,” he said. “What I can say, without any specificity because there isn’t any, is that we need to have compassion on one hand, and some kind of firm rule on the other. If we make a decision, then we have to stick with it.”

Ms. Rice explained that the administration has researched different types of equipment to store phones and noted that various schools have tried different approaches to implementing the policy. “It really is a lot for us to weigh,” she said.

According to the New York City Department of Education’s current cell phone policy, students may bring cell phones, computing devices, and portable entertainment systems to school, but must follow their school’s specific rules. At THHS, the current policy allows phone use in designated areas like the cafeteria, courtyard, and auditorium, while usage in classrooms and gyms is allowed only with a teacher’s permission. However, under the proposed policy, these exceptions may not exist.