A new Regents grading policy implemented to streamline the grading process and increase accuracy has come under fire for doing the opposite. Numerous technical difficulties marred the city’s new plan for computerized, centralized grading, resulting in an expedited grading process that rushed teachers to finish grading before graduation ceremonies in late June. Following a significant drop in the rate of students achieving mastery level on the English Regents at Townsend Harris, many members of the school community have questioned the accuracy of the grades. Save one, all appeals to the city and state to review grades deemed “questionable” have been denied.

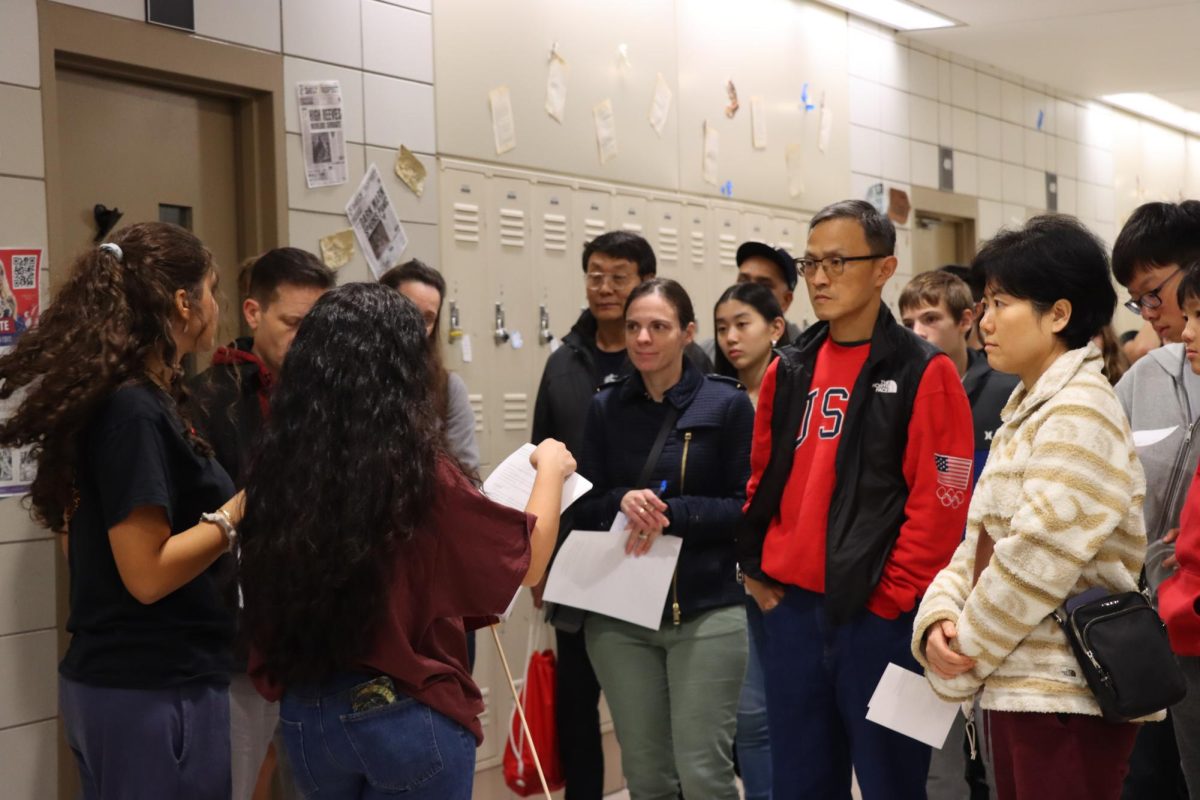

The change in grading policy is in response to a state mandate meant to ensure that individual teachers do not grade the exams of students in their classes. Whereas most other schools in the state responded to the mandate by continuing to grade the exams ‘in house’ but requiring teachers to grade the exams of classes they did not teach, the New York City Department of Education went a step further and decided that teachers at city schools could not grade an exam taken by students enrolled in their schools, whether or not they taught them. In mid-June, teachers from high schools across the city had to report to grading centers to jointly grade the exams of the entire city’s student body.

After conducting a series of small-scale pilot programs over the past two years, the Department of Education declared an electronic scanning system to be more efficient than the traditional pencil and paper grading system.

“We found that it saved time since teachers didn’t have to unpack the exam and then repack it, and they didn’t all have to be at the same site to grade them,” said Shael Suransky, chief accountability officer of the New York City Department of Education.

To facilitate this system, schools shipped student exams to Connecticut, where McGraw Hill scanned the exams for grading. Teachers at grading sites then received the scanned version of the exam (without the student’s name or the school’s name) over the Internet using software developed by McGraw Hill.

When implemented, the system experienced a lag due to the high volume of exams processed. This resulted in teachers staring at blank screens for hours on end.

“There were times when nothing was coming up because we had to wait for scanning,” said Social Studies teacher Charlene Levi, who graded the Global History and Geography Regents at Martin Van Buren High School.

Ms. Levi said that, had she been grading the exams in-house, she would have graded 350 exams and would have been done grading in two days. With the computers, after two days of work only 42% was completely graded.

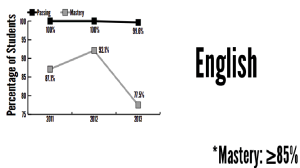

The new grading system had little effect on the majority of the tests taken at Townsend Harris, with one notable exception: the English Regents. This past June was the first time in several years that the passing rate for the English Regents was below 100 percent. More surprising was that the mastery level (students receiving a grade of 85 or higher) decreased 15 percent from 2012.

The disparity between some students’ grades on the Regents and their grades on the AP English Exam has members of the Townsend Harris community questioning the reliability of the results.

On the AP English Exam, which is widely accepted as the more challenging test, the class of 2014 had the highest passing percentage and received the most 4s and 5s in the history of the building.

“The results on the AP exam show that something went very wrong with the scoring of the Regents,” said English teacher Joseph Canzoneri in an email he sent to his AP English students after the release of the AP scores. In a later interview he said, “It doesn’t make sense how kids could increase greatly with the AP scores and tank the Regents. It’s a statistical impossibility.”

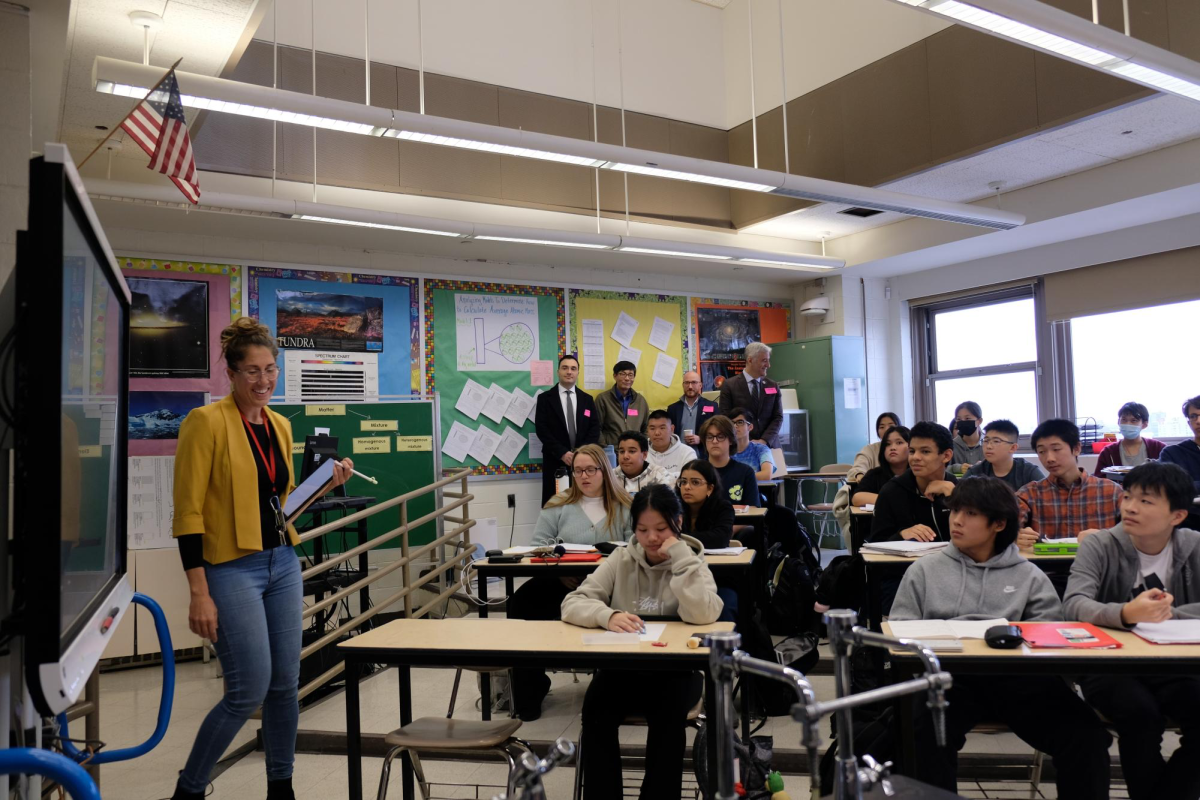

English teacher Katherine Yan, who graded the English Regents at Thomas Edison High School, explained that there “may have been several factors” that affected the drop in the mastery level rate.

Ms. Yan said, “If the training is different and [the graders] are from different schools, and they have different standards, it’s hard to get everyone on the same page. The rubric is there to keep us objective but it’s still hard to do that with so many teachers from different schools.” She said that the difference between one grade and another on the scoring rubric can affect the final Regents grade by “a lot” of points.

Since the English Regents requires students to reference texts they’ve read, students often refer to texts taught in their schools. In the past, this made it easier for teachers at their school to grade the exams as they would be more likely to be familiar with the texts the students analyzed. At Ms. Yan’s grading site, supervisors reprimanded teachers for asking each other questions about tests, so if “someone behind you didn’t know anything about Lord of the Flies, they couldn’t ask any questions. Students are writing about all different texts and they can’t ask about it, so it might be hard to accurately grade somebody else’s student.”

Social Studies teacher Alex Wood served as a content supervisor at Brooklyn Technical High School. Mr. Wood said that, though he didn’t discourage people from talking to each other, the computers made “teachers feel like they’re grading machines and it hindered them from asking advice to give accurate scores.”

Senior Jonathan Chung did very well on both the AP English exam and the SAT subject test for English, yet he received below the mastery level on the English Regents. He said the Regents was “more like a test to see how well you can spell things out for people, and not so much of insight and comprehension.”

With parents, students, teachers, and administrators skeptical of the results, the option for appealing the test grades became more and more desirable.

The principal must send appeals to the superintendent. If there are a small number of appeals, the superintendent makes the call on whether they are valid, but if there is a larger number, the appeals might get sent to the state.

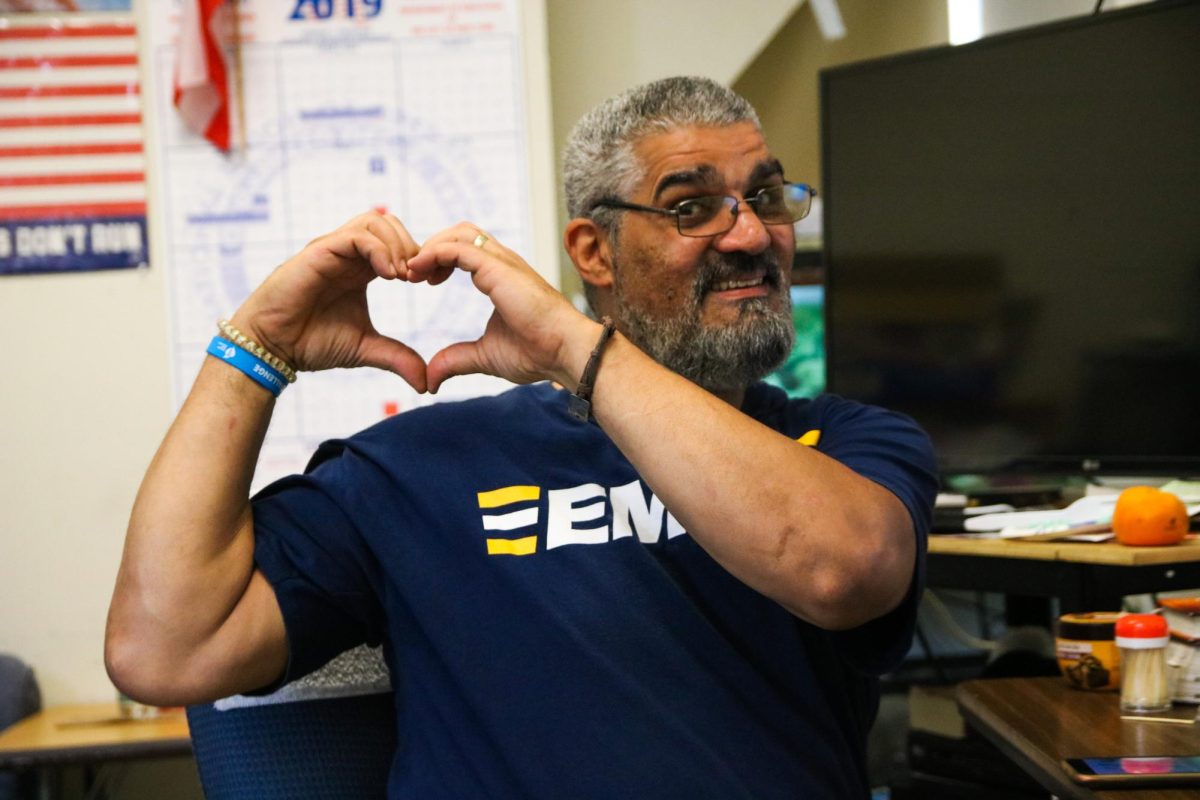

Principal Anthony Barbetta appealed all “questionable exams, meaning students who failed or who just missed mastery by a point or two.”

Only one appeal went through; all others were denied.

“They basically wanted us to find clear cut answers that were marked wrong but we couldn’t find it,” said Mr. Barbetta.

Since the essay grading depended upon live scorers, it was the focal point of the appeals, but the school did not receive the actual grades scorers gave to students’ essays; they only received the scans of the essays back. This made it difficult to prove that a student who received a grade below the Mastery level was graded improperly.

One of Ms. Levi’s students appealed after receiving a grade below mastery on the Global Regents. “Because it was a passing grade the department didn’t even want to deal with it,” Ms. Levi said.

During the process of shipping the exams to Connecticut, the DOE lost the exams of numerous students from other schools; these students had to return in August for retakes. For Townsend Harris, one exam was not scanned. “Originally it was put in as a failing grade, and it turned out to be in the high 90s,” said Mr. Barbetta.

However, not all feedback was negative.

Once the scans were available “it was much faster to grade them on the computer,” said Ms. Yan. “Normally I wouldn’t be able to grade 20 exams an hour. This was much easier; you just click and go on to the next one.”

Ms. Levi added that while the graders “still had to read kids’ handwriting, it was cool to have it come up on the computer.”

Despite the positives, the participating teachers did not approve of the new policy.

“It feels like we can’t be trusted, like we’re going to compromise our integrity over Regents Exams,” said Ms. Yan.

Mr. Barbetta agreed: “I think the system doesn’t trust us to be professional and I’m disappointed in that.”

The Department of Education did an audit two years ago and found that there were some schools where teachers were inflating grades.

“The way we know that is when we re-graded them, some of the exams that were at the passing mark weren’t in fact passing,” said Mr. Suransky. “It doesn’t benefit the student to pass them if they’re not, so the question came up of how can we create an efficient system where teachers grade Regents that are not their own and we came up with a possible number of options, one of them being electronic scoring.”

After the delay in getting all exams graded, which resulted in many students going to graduation without knowing if they did indeed pass the necessary exams, Mr. Suransky determined that “the technology of [McGraw Hill] was not good enough.”

On September 13, the Department of Education cancelled the remainder of the $9.6 million, three-year contract with McGraw Hill, opting for the customary paper and pencil grading this upcoming year. Teachers, however, will continue to be sent to scoring sites to grade the work of students from schools other than their own.

“Teachers will be sent to different sites to grade the Regents…[and] they won’t be scoring their own kids but they won’t be doing them on the computer,” said Mr. Suransky. “I hope we can get the technology to work in the future, but we are not comfortable with this company and its technology,” he added.

According to Niket B. Mull, Executive Director of Assessment, the city has “a number of practices to ensure a fair grading process” when teachers grade the Regents next year with non-electronic methods.

“I don’t think the problem was the scanning,” said Ms. Yan in response to news of the city letting McGraw Hill go. “It’s hard to read those essays when you don’t have knowledge of the text and then be able to accurately grade them. Maybe if the money was put into school funding then students would be able to perform better and then there would be no issue of cheating on Regents exams because there would be no need.”

The city will receive a refund from McGraw Hill for the June portion of the contract.