When I was in 8th grade, I had an English teacher who would give us the same reminder before every assessment we took, whether it was a brief pop quiz or a final: “If you must fail something today, don’t let it be your honor.”

Back then, I used to dismiss the saying. Cheating at my middle school was practically unheard of, except for the periodic homework sharing and last minute exchanges that often went like this: “How was the test? What was on it?” With only 13 students in a class, it would probably be difficult to copy someone else’s answers on a test without getting caught.

While I never thought much of it in middle school, I feel as if it became more common in high school. The reason is obvious. We need to go to college, but to go to college we need good grades. To get good grades, we can just cheat. What students don’t understand though is the paradox that accompanies cheating. People cheat to advance themselves academically, but by cheating they lower themselves morally. When they are caught they are marked as outcasts by their peers and educators. The very crime they commit to reach a higher academic standing undermines the moral and ethical principles that make someone respectable as a human being.

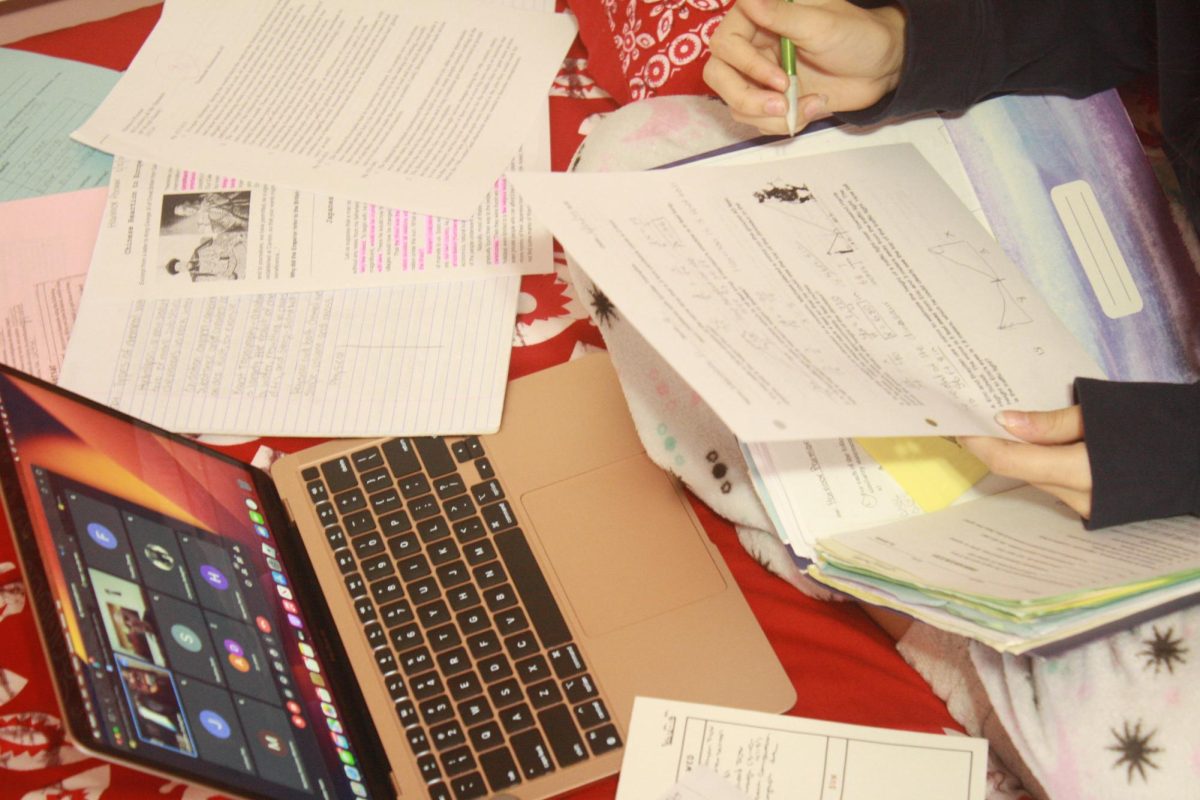

Perhaps students are not entirely at fault for attempting to obtain higher grades. Maybe it is a flaw in parenting and pop culture. Maybe parents failed to inculcate their children with these simple, obvious principles. Or maybe this is a way to cope with the academic demands thrust upon students by society, that the appearance of success is worth the detrimental act of cheating. Regardless, we teenagers have somehow concluded that cheating is not a grave issue, and is simply a part of academic success.

In fact, just a little over a year ago, news broke out regarding a cheating scandal at Stuyvesant High School, one of the most highly regarded public high schools in New York City. Many people who heard of the incident were stunned, especially because the cheating took place at such a premier school. These students were thought to be the best and brightest New York City had to offer, so why cheat?

Although cheating has always served as a means for subpar students to avoid flunking out of their classes and subsequently attending summer school, it is not uncommon for straight-A students to cheat as well. This kind of behavior has become a safety blanket of sorts—to ensure that one does well in class and to protect one’s chances of attending a reputable university. But the truth is, cheating only provides students with a false sense of security. The safety blanket of cheating may preserve one’s good grades, but it also greatly hinders one’s ability to learn. How can students expect to learn if they don’t even try in the first place?

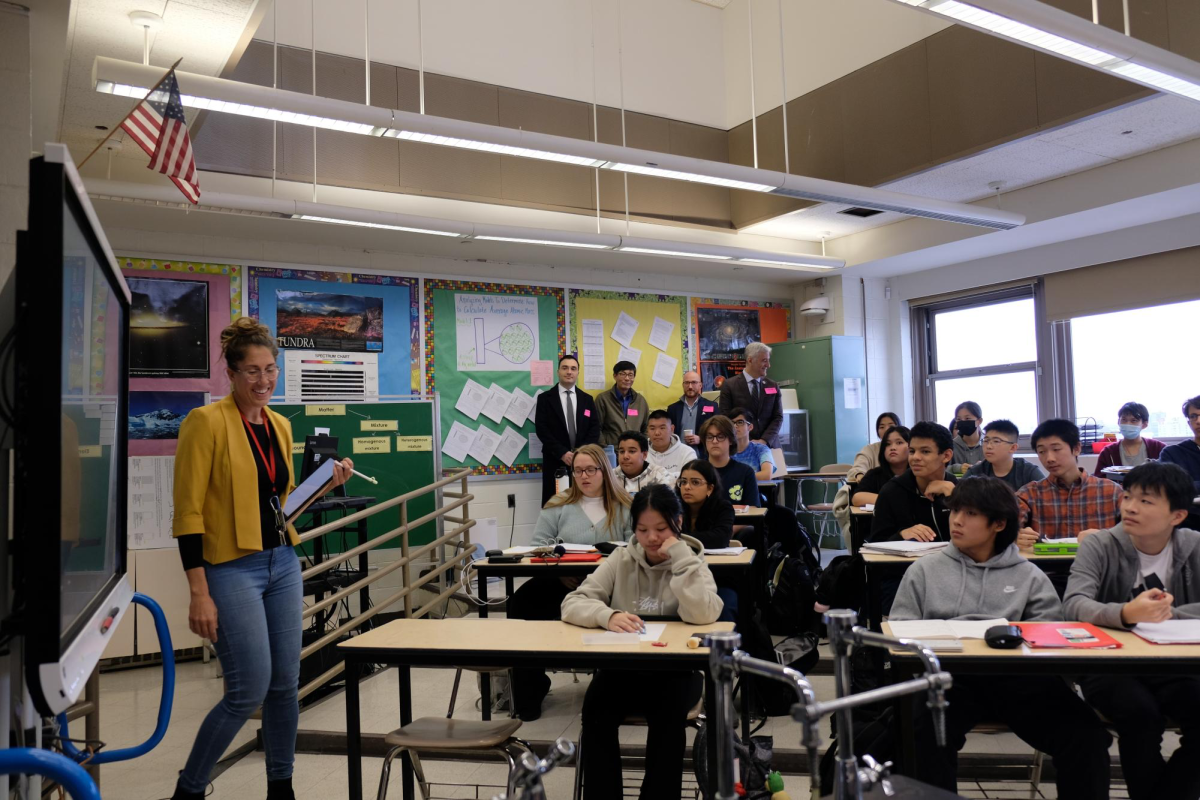

Another concern of mine is that students do not seem to realize how badly their actions affect their teachers. Working as a teacher’s assistant for a SSAT test prep course, I have seen the effects of cheating firsthand. One of the girls I was instructing had copied a large portion of another girl’s essay as well as a good deal of that girl’s answers. I was so proud at first because I thought that same girl had just worked hard to improve, but when I graded the other girl’s answer sheet, I noticed all of the similarities and I knew right away that the girl had cheated.

I was crushed. All of that initial gratification at her outstanding test scores disappeared right away. It was disappointing to discover that the girl had hoodwinked me, but it was even more disappointing to realize that I, as an educator, would not have been able to help that student. Her cheating disguised mistakes that I would have recognized and helped the student with. By attempting to cover up her inability to score well without extra assistance, she was really just trying to cut corners to achieve satisfying results—the same results that could have been achieved if she had trusted me enough to help her. How can I help a student who isn’t even willing to try to help themselves?