As Albany readies its 2023 legislative session, advocates are pushing a bill to free NY student journalists from censorship

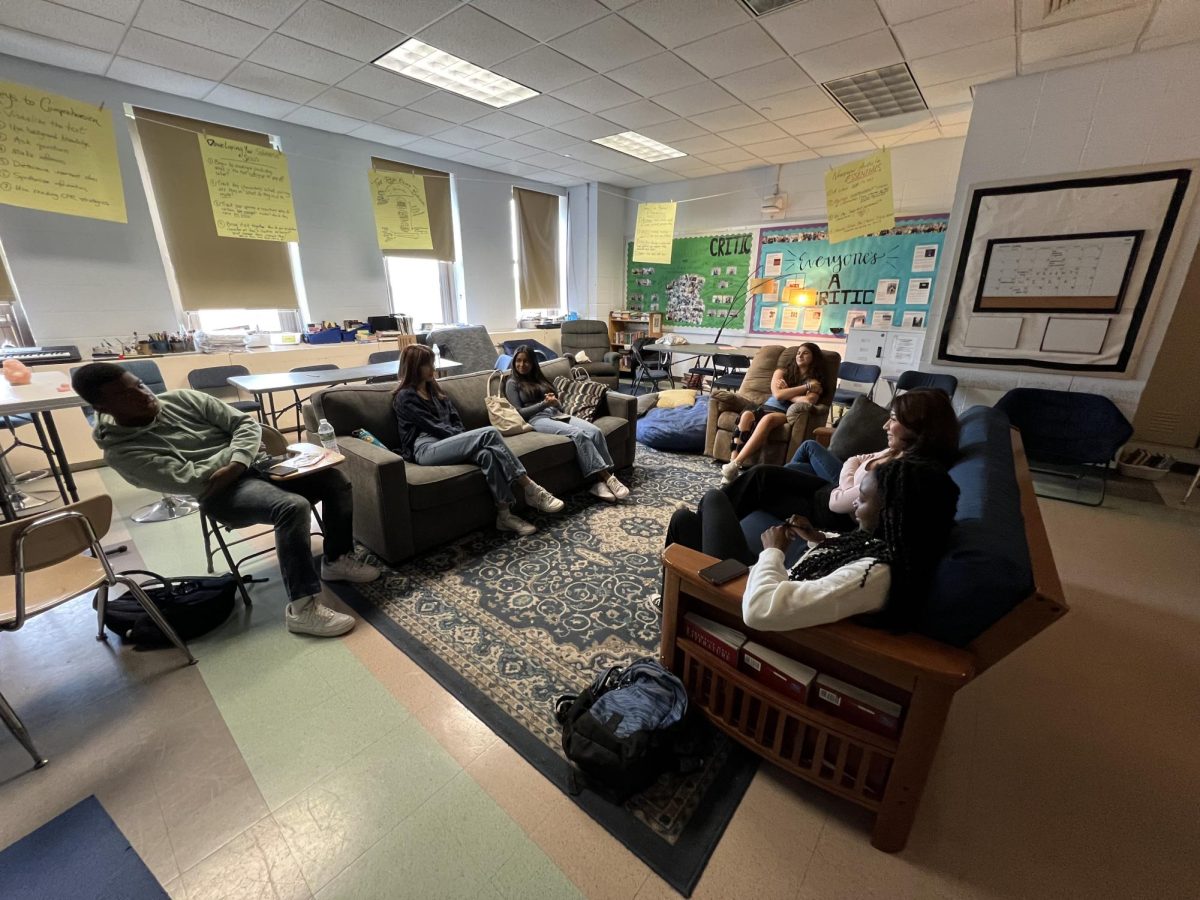

In November, The Classic published an article detailing a student press event with NYC Department of Education Chancellor David Banks. Face to face with a table of inquisitive teen journalists from across the city, Chancellor Banks voiced repeated support for student journalism amidst a wave of book banning, censorship, and curriculum conflicts sweeping the nation’s schools. Perhaps most significantly, he said that he would like to follow up on the Student Journalist Free Speech Act, a bill proposed in Albany by New Voices New York, a non-partisan coalition that advocates for the rights of student journalists. The proposed legislation, already in place in many states across the country, would prove a significant milestone in a decades-long effort to prevent student newspaper censorship.

The New Voices New York bill outlines an array of reforms to expand, or, in many cases, definitively establish the freedoms of student journalists. The bill states that student journalists should be in charge of making content decisions in student publications, and if administrators declare an article unsuitable for publication, they would be required to promptly justify their actions to the journalists in charge of the given piece. Furthermore, the bill prohibits administrations from penalizing newspaper advisors for supporting student reporters, and if an individual ever feels threatened by the published work of student journalists, it protects schools from a potential lawsuit the individual may file. The Student Journalist Free Speech Act does not do away with all restrictions on what students can publish; content containing libel, invasions of privacy, or violation of state or federal laws would remain strictly prohibited.

Mike Simons, a high school yearbook adviser and advocate for the New Voices bill, said, “If we can bring together people along the political spectrum in a coalition that just stands in support of student voices, I think that’s a pretty powerful thing.”

However, legislation protecting student journalism has not always been successful, which makes the NVNY bill’s future murky. In large part due to Albany’s drawn-out process of reviewing legislation, the bill is currently on its fourth version, although it has seen few major changes since its inception. With only one-month intervals open for reviewing proposed bills, one would need to wait for the next window if a proposal was overlooked the first time, which is entirely possible given the sheer number of bills a single committee must look through. Furthermore, New York does not have testimony or hearing-style procedures.

“We can’t have a student journalist sit down in front of ten senators,” Simons said. Absent open hearings, NVNY is hoping to go to Albany once again to reach out to legislators one at a time, following their last visit in 2019.

Simons said that the goal now is “to continue to focus our efforts on accruing more and more sponsors. We found [that] many of the legislators…don’t even know that this is an issue.”

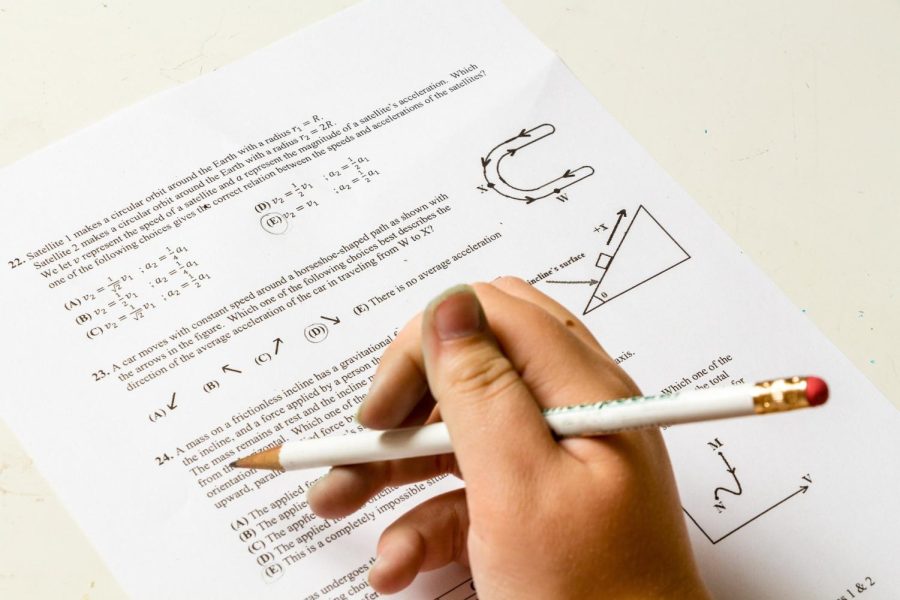

The countrywide clash over student first amendment rights on the legislative level began with the court case Tinker v. Des Moines. In 1965, Mary Beth Tinker, along with several others, wore black armbands to school in protest of the Vietnam War. In retaliation, the school suspended the students until they agreed to remove their armbands. The students consequently filed a lawsuit, arguing that the school district had violated their First Amendment right to free speech. Ultimately, after making its way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, a majority opinion ruled in favor of Tinker, setting the precedent that school officials could only censor speech if it substantially disrupted the educational process or invaded the rights of other students. For two decades, this decision applied to student first amendment rights in schools, but in 1988, a case came to the court that specifically related to the freedom of the press rights of student journalists. The U.S. Supreme Court case Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier redefined what Tinker had established for journalists.

In 1988, student journalists at the Hazelwood East High School newspaper wrote two articles, one on divorce and one on teen pregnancy, that were later deemed inappropriate and removed by the principal. The students filed a lawsuit, claiming a violation of their first amendment rights. After reaching the Supreme Court, a 5-3 majority ruled that articles published by school newspapers can be removed for “legitimate pedagogical concerns” or for being inappropriate for a school environment at the principal’s discretion.

Fress press advocates have raised concerns about the Hazelwood ruling in the years since its release. In practice, critics maintain that what constitutes “legitimate pedagogical concerns” is unclear and allows administrators too much freedom to censor articles on topics that might make the school look bad in the name of a “pedagogical concern.” As a consequence, the New Voices seeks to clarify Hazelwood’s language and ensure that students have a process for publishing content without fear of blanket censorship that is frequently carried out without justification from administrators. As Simons pointed out, the bill has so far been passed in 16 states in a bipartisan fashion, including Republican-dominated legislatures such as North Dakota and Democratic-dominated legislatures like New Jersey.

According to Mr. Simons, much of the opposition to the bill stems from superintendents who are afraid that student publications with more freedoms can make schools or school districts “look bad.” Supporters of the bill, on the other hand, claim that uncensored student newspapers have consistently reported on pressing issues that would have otherwise been ignored, leading to overall positive change in their surrounding communities. “When reported well—and ethically—our student journalists can start conversations that can then help inform, shape, and change the minds of our communities and schools, and arguably make them better places,” Simons said.

Today, the bill is being processed in the Senate Education Committee. As in previous years, NVNY is preparing another spring of advocating for the bill in the hopes that it can receive a vote. In 2019, members of The Classic were invited to speak on behalf of the bill. Though New York state does not currently have legislation that clarifies the Hazelwood case, Townsend Harris has a free press charter that does. At a press conference, then features editor Alyssa Nepomuceno spoke about the charter of The Classic, saying “[this] protection…should be enjoyed by all student publications in this state in order to spread the ability to freely be the voices of the students of our schools.”

Additional Reporting by Kevin Byun, Arianna Caballero, Justin Linzan, Pierre Marbid, Sophia Sookram, Annie Xiao, and Stephen Xing.

Your donation will support the student journalists of The Classic. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment, support our extracurricular events, celebrate our staff, print the paper periodically, and cover our annual website hosting costs.