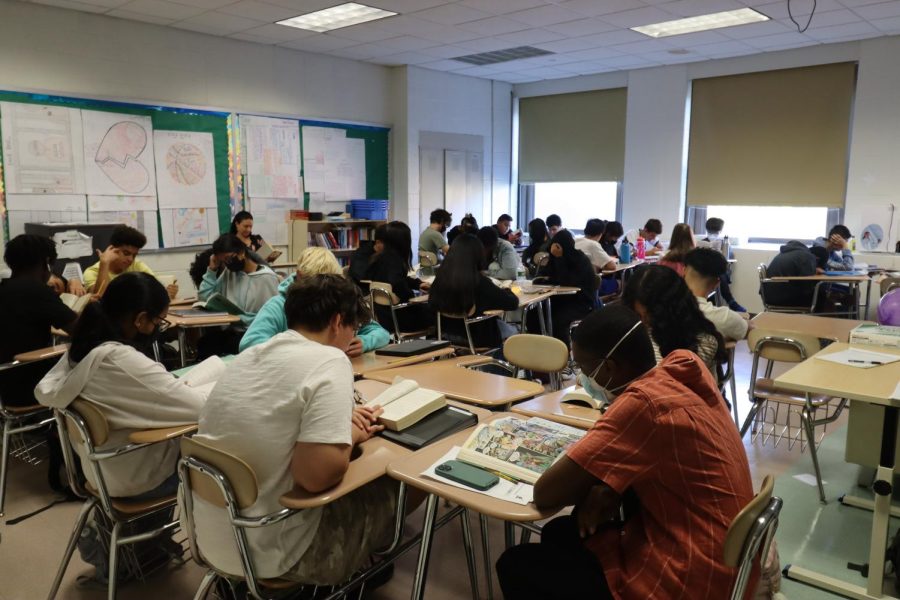

A student is learning conjugations in his Spanish class. He isn’t well versed with the vocabulary, so he decides to take out his phone to look up a word. As he browses the Internet, he discovers new terms, and on the whole, has learned something new. Suddenly, the teacher spots his phone, and promptly confiscates it. The teacher tells the student that he can pick up the phone at the end of the day, along with two demerits. Why was a student punished for looking up words and doing research? Because he was doing it on a phone.

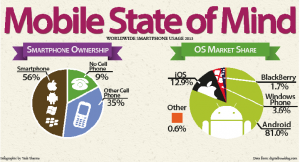

Most teachers dismiss phones to be nothing more than devices that distract students. This view is outdated. The smartphone, a clear-cut difference from the text-and-call devices used 10 years ago, comes standard with a calculator, a note-taking app, a reading app, and a web browser. Such capabilities cannot be ignored because of old prejudices. Smartphones are a part of the future, and no matter how much our teachers or the DOE may wish to deny it, they can be beneficial to us.

The main argument against smartphone integration in the classroom is that it will cause too many distractions and promote cheating. Teachers believe that students won’t pay attention in class, in favor of spending time on Facebook and Tumblr. After all, one can’t expect students to have self-control with ready access to such distracting websites. However, this argument doesn’t consider laptops and tablets, which are plagued by the same problem.

In the past, teachers opposed the integration of tablets and computers in the classroom. Their argument was similar to the one being made now: the Internet is a distraction. But this is where the folly lies: can’t laptops and tablets access the Internet just as well, if not better, than smartphones can?

To say that the devices serve different purposes is no longer an acceptable response. The only difference lies in size. Perhaps smartphones are easier to conceal (the primary cause for cheating concerns), but if they were allowed in classes, students would no longer have a reason to conceal them. If the devices are dealt with similarly to computers and tablets, a teacher can simply ask to see the student’s smartphone. If this seems like an invitation for teacher regulation, that’s because it is.

As much as smartphones should be allowed in classrooms, regulation should be tied into that privilege. Suspicion of what students are doing is only natural, but to completely shut the door on smartphones is a misguided means of policing students. They are in classes now, whether people like it or not. They are potential cheating tools now. There should be better rules that both make that cheating impossible and make their benefits available. Consider the famous Spiderman quote: “With great power comes great responsibility.” While smartphones present the possibility of distraction, that worry should be outweighed by how useful they would prove in the classroom setting. Some students will always abuse school policy, but to restrict the whole student body on the basis of a few cases affords a minority of wrongdoers the power to dictate the rights of an innocent majority.

Teachers reason that the classroom is a place for learning. We agree; the purpose of school is to prepare students for the future, whether that be college or a job. But if this is the case, then how valuable is an education of taking notes on paper and listening to the teacher?

Students often ask, “What is the real world application of what we’re doing?” With smartphones, there is a legitimate answer. Businessmen read emails, people read books, and videos record important moments. Never before could a device so small accomplish so much. To keep this wave of possibility out of the classroom is to separate the current generation from a device that has already changed society so much. This is a mistake and it ignores the reality of a world where phones are becoming increasingly useful.