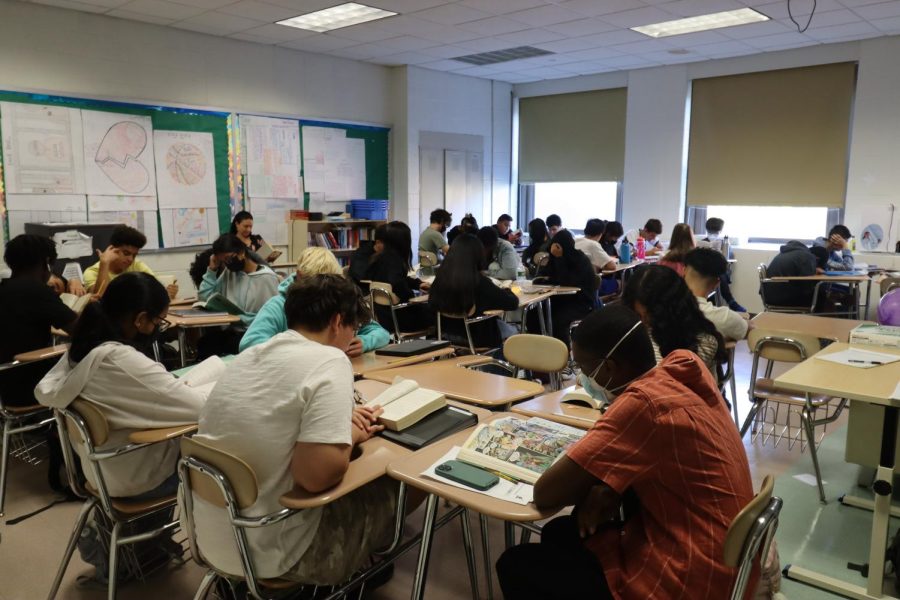

THE RECENT adjustment in Townsend Harris’s cell phone policy has been in effect for almost a month, allowing teachers to better facilitate in-class learning through technology. However, this update in the rules now begs the question: does a more lenient policy create more room to cheat?

In keeping with new rules, phones must be turned off and can’t be visible in the building. If seen or heard, they will be confiscated and referrals will be distributed. However, with permission, “Teachers may use cell phones to supplement instruction and learning.” Though this policy is meant to benefit teachers and students alike, it raises questions regarding the potential consequences of cell phone leniency in the classroom.

For Principal Anthony Barbetta, the extent of students’ freedom depends upon their maturity. “We think they’re mature enough to handle the policy. If we do find cheating we’ll have to look at the policy [again].”

While Dean Robin Figelman feels that using cell phones during class time would enhance the learning process, she is adamant in sticking to the current policy. “I’ve heard rumors from teachers that yes, [students] do use their cellphones to cheat, but I’ve never experienced that myself,” she said. “But I am sure that given the opportunity, students will use their phones to cheat; it’s just human nature.”

Based on a poll of the student body, 95 percent of students claim that they have never cheated with their cell phones. However, while small and seemingly insignificant, five percent of students still claim to have used their devices in order to find out answers during an exam.

When asked about the frequency of students using their phones to cheat, Assistant Principal of Humanities Rafal Olechowski acknowledged that it is hard to know for certain. “I know it goes on. Is it reported? No. Because people don’t always realize. But I know there’s been at least one case that they know of when someone took a photo of a test in another department.”

Physics teacher Joel Heitman doesn’t believe the new policy has altered the amount of cheating at THHS. “I haven’t noticed a change yet,” he remarked, “but time will only tell.”

Assistant Principal of Health, Organization, and Physical Education Ellen Fee also acknowledged that it can be difficult to crack down on illicit cell phone use. “Any time I hear of any incidents, I report it…so I’ve not heard of any instances that the kid didn’t get in trouble,” she said. “Do I hear things from other schools, and my own children saying how easy it is and how easy it is to fool administrators and teachers? Absolutely.”

Just how easy is it? Junior Abdoulaye Diallo says he sees it all the time. “[Students] go into the bathroom and pull out their phones. They pull up Google Docs and vocab,” he reported. “It’s not just for one class. It’s every class.”

Senior Minhaj Rahman reported seeing similar things on a daily basis. “When I was in the bathroom, a student was using his cellphone to look up questions on a test.”

Sophomore Adem Purisic believes that cheating will increase as a result of the policy change. “Now that we’re allowed to have them, numbers [of kids using cell phones to cheat] might go up.”

Yet, some students feel that a stricter cell phone policy is not the solution to cheating.

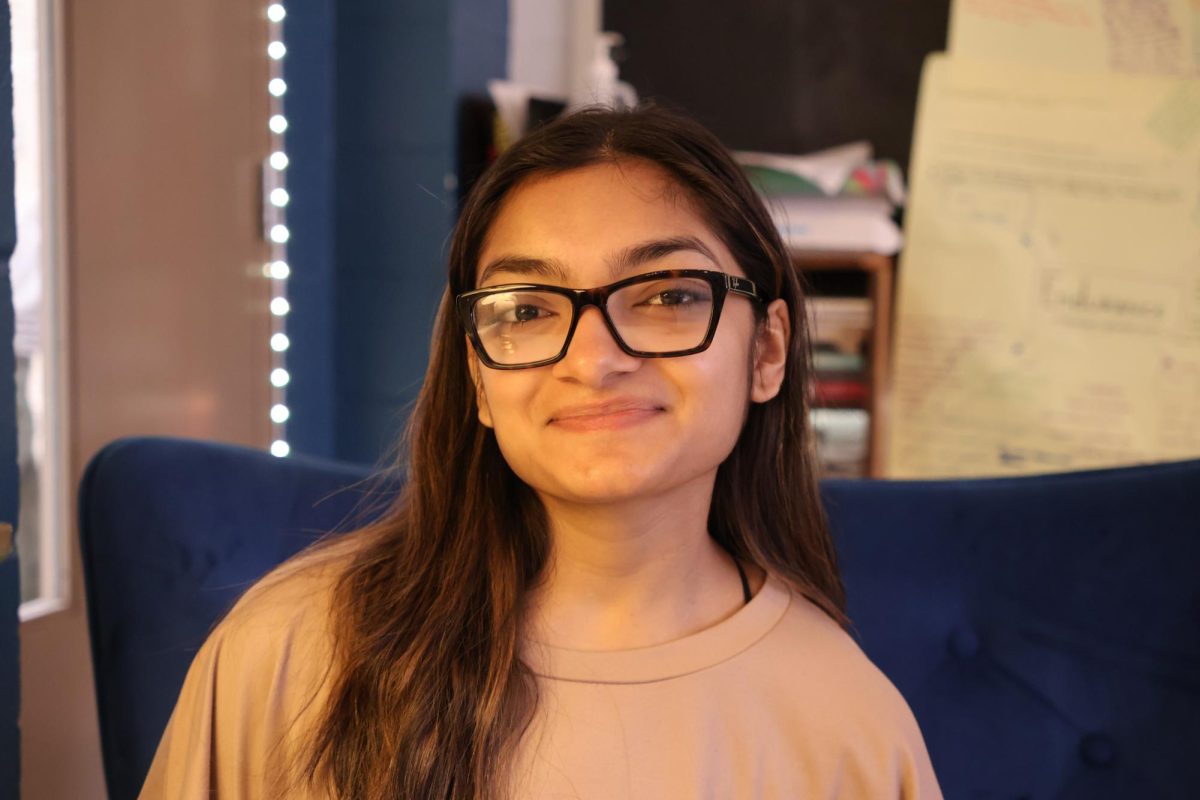

Freshman Michele Katanova has already found this to be true. She felt the number of students who cheat using other means is much higher. “I’d say that more than that, 20 percent, cheat [using other methods],” Michele explained.

Adem has seen examples of this cheating as well. “People make little study guides in the palm of their hands,” he commented.

Junior Pamela Wong pointed out that cheating can occur more casually and subtly, regardless of the involvement of technology. “Everyone tells people what’s on the test; it happens in every school,” she remarked.

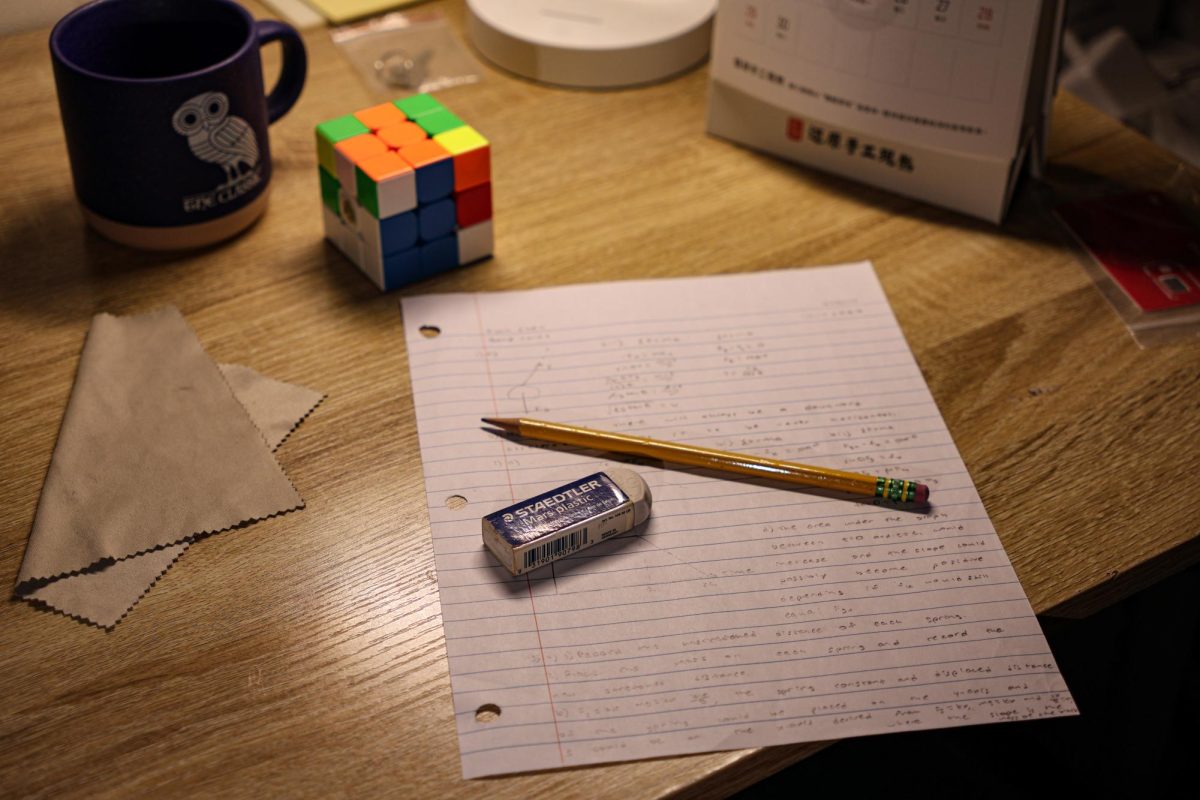

To combat cheating, most teachers remain on the lookout. Latin teacher Jonathan Owens is diligent when his students take exams. “I keep moving. I’m always watching,” he said. “I will hover around more.”

As Mr. Heitman commented, it can often be difficult to catch someone cheating. “To say that somebody’s cheating, you really have to see it 100 percent without any source of error,” he said. “That’s hard to do.”

Some have tried to counteract cheating in a different way — by changing their tests. Mr. Olechowski said, “I’m always thinking about what kind of assessments are meaningful… If they’re tested on something that they can quickly cheat on with their phone then maybe I’m not interested in that assessment.”