In November 2015, the attacks on Paris provided yet another reminder of the dangerous world that we live in. For many Harrisites, violence overseas may seem like a distant problem, but a large number of students and community members have family that live in areas that have experienced violence and danger in recent years, be it manmade or the result of a natural disaster. This special feature focuses on the stories of students who have these long distance connections and who come to school burdened by the worries that they hold for their loved ones overseas.

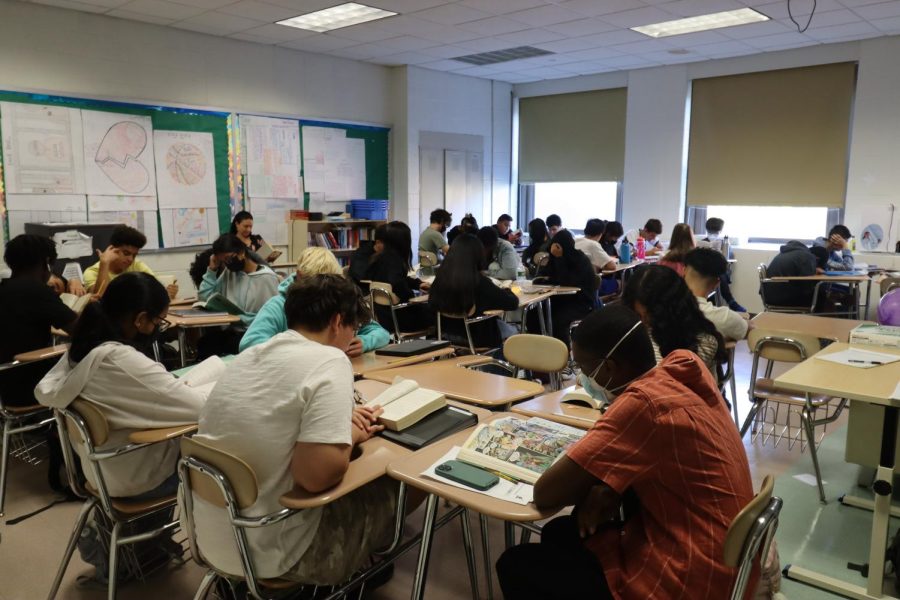

Given that “stress” is a word most often associated with homework and examinations in academic environments, we tend to overlook its presence in students rooted in situations bearing more gravity. It’s not unusual for teachers and guidance counselors to intervene whenever students are undergoing problems at home, but what if “home” is thousands of miles away? Many of the students at Townsend Harris are the children of immigrants, meaning that much of their family resides overseas, along with whatever international conflicts and tragedies those regions may undergo. As a result, students and their families have to cope with fear and anxiety for their families’ safety and well-being.

Natural disasters may occur oceans away, but their impacts reverberate throughout the student body, especially in students who have families in the affected areas. In 2013, Typhoon Haiyan, also known as Hurricane Yolanda, hit especially hard and devastated parts of Southeast Asia. One of the deadliest hurricanes in Philippine history and of all time, THHS students have felt the personal effects of the event.

“Those living in my grandfather’s house (my grandfather, grandmother, older cousin, and my uncle) had to shelter at the second floor of the house because the whole first floor was flooded, almost reaching the second floor,” senior Julian De La Rosa remembered. “My grandfather was soon traumatized by that experience and my relatives had to relocate. [A] bunch of family relics and valuables such as pictures were lost as well.”

The 2010 earthquake in Haiti, which resulted in over 100,000 deaths and caused major damages to landmark buildings and infrastructure vital to daily life, struck at the hearts of many in the United States. “My family was fine, but they are traumatically scarred for life,” senior Florebencia Fils-Aime said. “When New York experienced an aftershock, my cousin was in tears because she thought that she was going to deal with another earthquake again.” The Nepal earthquake this past year also devastated thousands.

Political instability and tensions also pose strains of immense proportions, incomparable to presidential campaign shenanigans or the congressional deadlock we have in the United States.

While the largest Christian church in Egypt, the Coptic Orthodox community remains a minority in the country and has been targeted and attacked. “Churches have been bombed and burned down. People have been killed for absolutely no reason at all,” junior Marina Aweeda commented. “It’s much safer now in Egypt than it was during the years of the revolution, but it is still a dangerous place for my family.”

While tensions in the Middle East seem distant and nothing more than stories in newspapers, many students have personal connections to these circumstances. Rachel Chabin, alumna of the Class of 2015, related that “My uncle missed the birth of his grandson and a related religious ceremony here because he felt he couldn’t leave his wife and children alone when the fighting was particularly intense. Their ability to come and visit is always subject to the political climate they find themselves in at the time.”

“Having family in Israel means we can hardly go a dinner without talking about the latest incident, one of President Obama’s policies, or some comment made by Prime Minister Binyamin [Benjamin] Netanyahu,” Rachel continued. “When we hear of an attack in Jerusalem, I think we all listen a little more closely, until we know for sure our family wasn’t involved.”

The recent Russian-Ukrainian conflict that began with the March 2014 invasion of the Crimean peninsula overturned post-Cold War norms and revived military operations in eastern Ukraine. As senior Yuriy Markovetskiy describes, it is difficult to have politically active family members in a region sensitive to political insurgency.

“My uncle and his friends were among the [Peace Protesters] that went to the capital a little while ago,” he said, referring to the protest camps set up in Kiev since last November. “My uncle went there and we couldn’t stop him, being on a completely different continent… thank God he left before the violence really started.” Earlier this year, reports emerged of police storming the protest camps, leading to dozens of deaths in each. “My family’s fine, and I’m grateful, but we still worry.”

The biggest impact of such circumstances on students and their families in the U.S. is the fear and concern for their families’ lives and well-being. Sophomore Niyati Neupane, who had family living in Nepal during the earthquake, recalled, “The day of the earthquake, my mom was so shaken up that she called my relatives a good number of times. They weren’t picking up though. Even after she learned everyone was okay, she kept calling to make sure. This makes my entire family here appreciate the relatives we left behind Nepal.” Senior Max Lacoma, who had family in Paris during the Bataclan attacks in November, commented that, “When the attacks hit a couple weeks ago we were all very scared until we were finally able to call them and hear that they were okay.”

The Internet has eased communication with those far away, with daily use of social media, video chatting, instant messaging, and email, in addition to long-distance calls. Many students who already keep in contact with relatives overseas, do not find a difference in their communication habits, but only find their need to speak with their family more precious.

“[The hurricane] definitely caused relatives living in America to stay in close contact, but it didn’t make a difference because we always communicate and keep the family close knit with or without disaster,” Julian said.

“[My uncle and I] communicate on Skype about three or four times a week,” said Yuriy.

While not much directly changes in the dynamics of students’ everyday lives, tragedies overseas strengthen students’ appreciation of their loved ones, as well as of their own circumstances. Junior Alyssa De Guzman, whose family has been affected by hurricanes in the Philippines, expressed, “My parents emphasized how thankful we should be for not being in the face of these disasters and to thank God for His guidance to those who were.” Rachel agreed, adding, “the situation makes keeping in touch with my family more of a priority, especially when reports of violence filter in through the news and I know they live relatively close to where it happened.”

“Nepal has always been a poverty-stricken country,” Niyati reflected. “Due to the earthquake, the situation has gotten so much worse. I have a deeper desire to do whatever I can to help Nepal. I want to raise money and just donate to all the needy. I know that when I get older, I will do all that I can to reform my nation.”

In the age of Google searches, Twitter Moments, breaking-news notifications, and “trending stories” tickers, the Internet has become a vast database for news, replacing the pervasiveness of traditional paper and televised sources. People are especially turning to social media, which fulfills the need for speed and conglomerates a multiplicity of voices, conveniently located on a single platform. While major news networks use social media to disperse their content, ordinary citizens enter the reporting process by sharing articles, their first-hand accounts, and their own opinions. This invites all—including students—to participate in a forum for exchange on various topics.

Last year, The Classic covered the complications of online debates, focusing on questions about the level of respect and the role of the administration in such arguments. The issue of freedom of speech remains a key player in our consideration of social media use, as Facebook continues to be a platform for students’ political beliefs–but can lead to arguments that devolve into bullying. Freshman Matilde Cardoso commented that “Discussions may start out very calm but it doesn’t take long for them to erupt and become heated arguments very quickly.” Some feel that the line between respect and personal attacks is blurred as decorum is forgotten amidst passions.

Recently, tensions flared over discussion of media and bias for Paris, in light of the terrorist attacks in November at the Bataclan theatre. When a student posted her belief that a double standard existed with regards to the lack of attention to bombings in Middle Eastern countries, compared with the solidarity with Paris demonstrated after the Bataclan attacks, another student shared her post—calling her a “fool.” Many saw this as rallying opposition to not only the ideas stated in the post, but to the original poster. Such situations have raised questions about the efficacy of Facebook as a platform for political beliefs and discussions.

“These debates usually have a bunch of people ganging up on each other saying hurtful things that stray away from the topic,” senior Michael D’Arcy reflected. “As a bystander, you see a lot of personal attacks and people who have no idea what they are saying.”

Many students believe it is important to have an outlet for political beliefs. “I think it’s important that people hear the views and opinions of other people,” commented junior Sabrina Cheng. While current affairs occasionally find their way into classrooms, instructional time for most classes usually does not include discussions of students’ political beliefs. Social media becomes the alternative, allowing for many perspectives to be spoken and the practice of freedom of speech without fear of retribution from school authorities.

Junior Casey Ramos agreed, adding, “I think the beliefs are safe when posted on Facebook, with the exception of radical views because they tend to garner a lot of unpopular attention.”

Dina continued, “People will always disagree about things and you will always have to form an opinion, so it’s good that people at least express enthusiasm about important topics.”

However, Facebook as a bastion of free speech is often held to examination when arguments become based in malicious comments. Michael expressed, “I don’t think Facebook is a good platform for political beliefs because you can not know for sure if these people posting on Facebook are being truthful or are just saying crazy stuff for laughs.” It is difficult to expect everyone on the Internet to have polite debate, with factually-sound arguments.

Casey added that, “responses to political posts often start small, but stances and people pile on until the focus is stretched from its original direction. Things tend to get personal; [an] immigrant defending immigrants are called out for it, the privileged speaking on privilege are called out for it, too.”