(n.) Backlash from the student body in the event a minority student is admitted to a competitive college.

Let’s give it up for Affirmative Action, every black college applicant’s new best friend. Without you, AA, we could never have made it to such great heights. Yes, we know, we were the ones who sat for college interviews and scored well on standardized exams. But, in the end, it was really you who got us into college, or, at least, that’s what everyone tells us.

It’s become a poisonous social norm to attribute the acceptances of minority students to top colleges to Affirmative Action rather than the actual qualifications of the applicant. Every time a minority student gains admittance to Ivy League or other top tier institutions, his entire academic and extracurricular profile essentially gets blacked out in a sea of negative reactions. Take a walk through the halls of Townsend Harris and listen to snippets of conversations such as, “She only got in because she’s black” or “He wasn’t even that smart.”

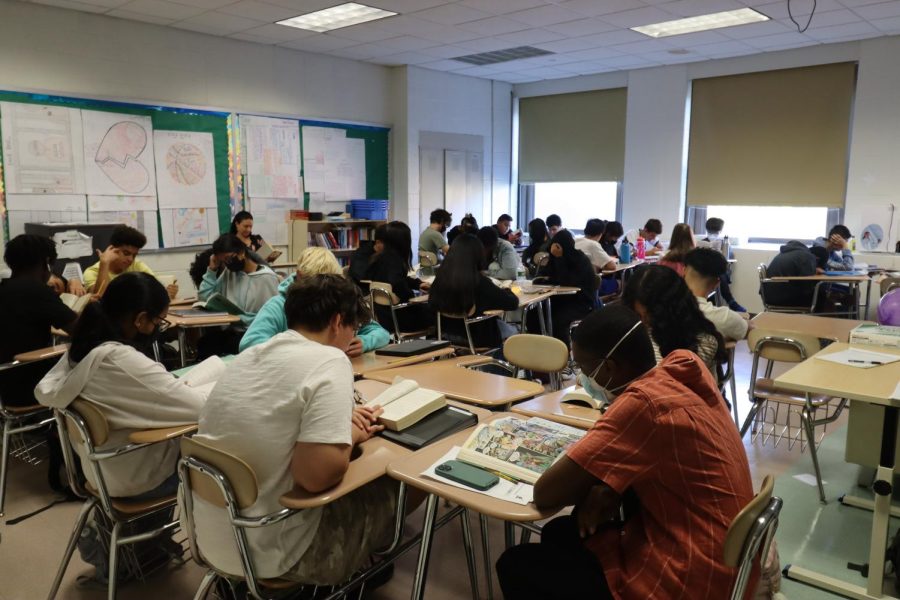

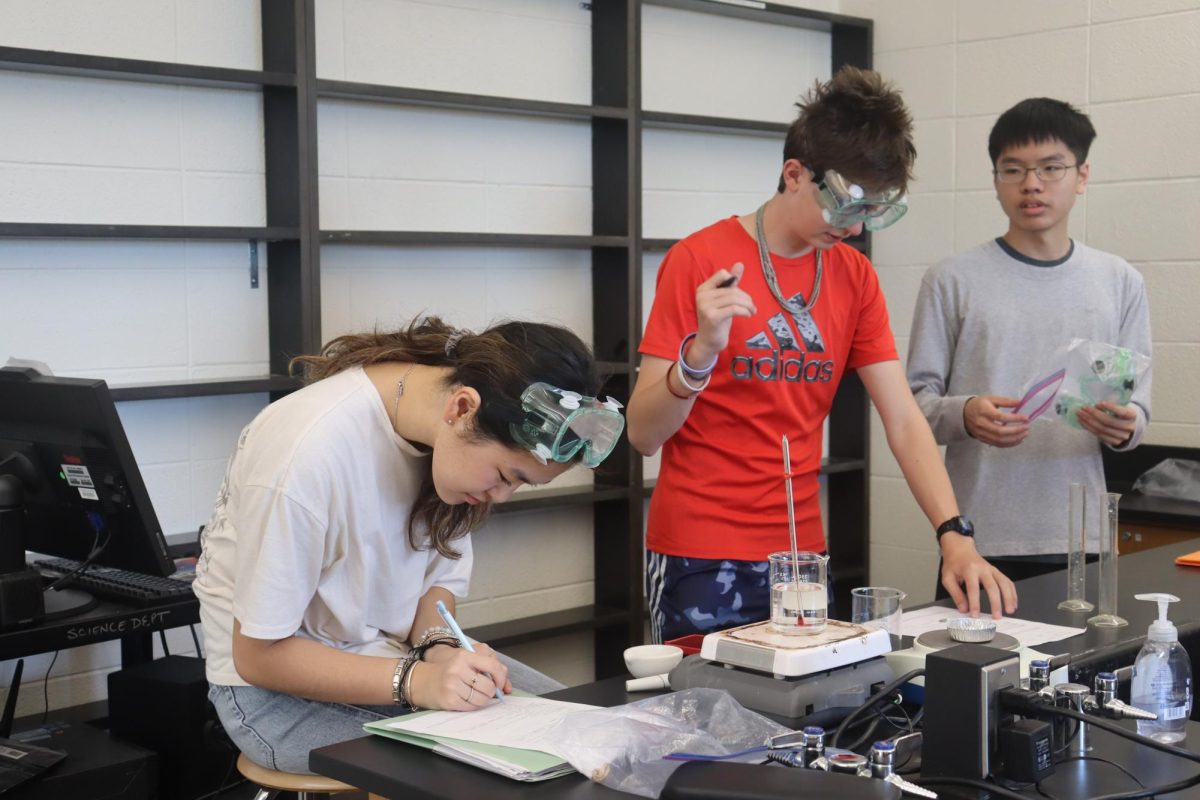

It’s shocking to think that in a school such as THHS, where all students are academically driven and many are instrumental members of clubs, teams, and publications, this mentality still exists. Rather than looking at the hard work of one individual, students judge others superficially, a toxic trend hypocritical to the claim that THHS is different from other cutthroat, academically competitive schools.

What’s even worse is that there are many students from minority backgrounds who keep quiet about their acceptances, just to avoid the imminent blacklash. It’s wrong for a young, accomplished student to feel silenced in the aftermath of his success, no matter his race. It’s wrong for a student who worked just as hard, if not harder, than her peers to feel put down by statements that chip away from her happiness.

As a result, Affirmative Action essentially becomes an excuse for why one student was chosen over another of different race. People tend to speak about Affirmative Action as if it’s a lottery system. Throw a bunch of black students in a hat and pick out one, two, or, if we’re lucky, five to be in the next graduating class. However, Affirmative Action is a policy meant to level the playing field across all demographics and socioeconomic classes. Many argue that the playing field is indeed as level as can be. After all, segregation ended in the 1960s. But just because black students can drink from the same water fountains as whites doesn’t mean the damage has been repaired. The racism that pervaded society up until the 1960s stripped opportunities not only from individuals in that time period, but also from future generations of their children.

This, in turn, suggests that racism pervades our society up until today, which is an accurate claim to describe a country built upon the aching backs and feeble knees broken by white supremacy.

In Ta-Nehisi Coates’ “The Case for Reparations,” an article published in the June 2014 edition of The Atlantic, Coates’ underlying message that today’s American white identity rests on the shoulders of the “plunder” of blacks is hard to stomach. If we, as American citizens, are to squarely face our history, we face a history in which American federal law lended itself to reducing blacks to social pariahs and untouchables.

It is an all too common mentality to leave the past in the past, but it is undeniable that the past threads itself into the present. This is not to cast blame onto the white men who threw us onto boats and shipped us off to the colonies, but to acknowledge that the past has inflicted tremendous, persisting damages unto the black race in America.

For each one of our successes, for each one of us that emerges from the low probability of leaving the ghettos, there are thousands of us left behind, forever stuck in the group still affected by the past.

For those of us that do make it big, we appear to close the “accomplishment gap,” the space between the extent to which whites and blacks have contributed to society, giving off the image that racism is obsolete. Although the hours our ancestors spent picking cotton under whip-wielding slave masters are well-past the average accomplishment, the harsh truth is that we have barely begun closing the gap. We still live in a society where blacks must work twice as hard, where women must work twice as hard, and where the poor must work twice as hard as the white man and, still, the fruits of their labor will not be a step in the right direction, but a single, miraculous success story, coming to a theater near you in 2020.

When I was younger, my father used to tell me that I, a black woman, would have to work twice as hard and endure twice as much as my white counterpart to make it to the same place as she.

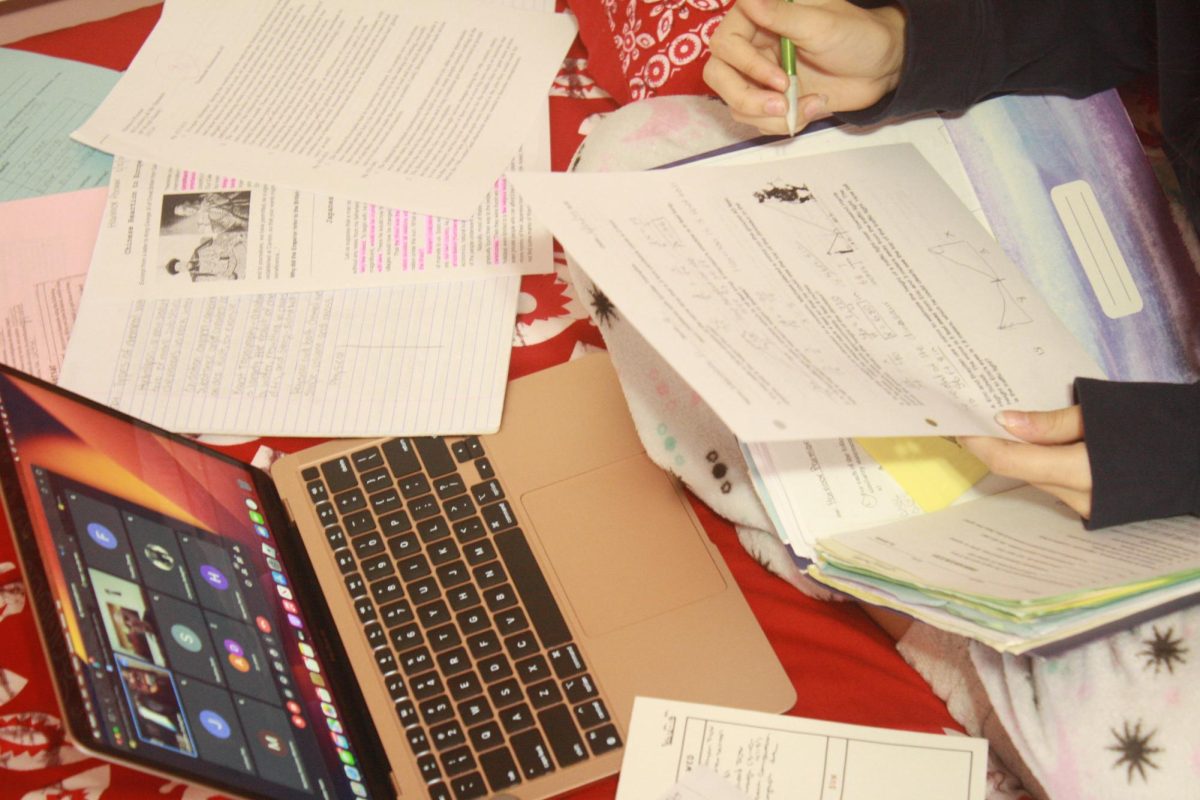

I did not fully understand what he meant, but as I matured, I began to comprehend the disparity in opportunities between the races. I find my own success, currently perceived as an anomaly, one that could have never been possible without a booster seat that launched my five-foot -one stature above the heads of taller, more qualified men and women; it is perceived as if I waved a tantalizing sign to admissions counselors: “PICK ME, I’M A BLACK GIRL.”

Two centuries ago, the pool of college applicants was a sea of white. Social Darwinism is a relatively polite term, but it was essentially white supremacy at its finest, once again. College admissions are not the only clean, uncolored surface of American society. If we turn back the clock, in white neighborhoods across the country, local governments were in full-fledged support of efforts to “keep up the neighborhood.”

This may bring to mind images of picking up stray litter and curbing the wastes of man’s best friend, but careful decoding will reveal the correct translation to be: “keep the blacks out.” In the 1940s, an African-American doctor moved into a house in Chicago’s Park Manor neighborhood, a white area. Soon after he moved in, a housewarming party (read: mob) of white residents greeted him with a classic pelting of rocks and fireworks show on his garage. The doctor, perhaps wisely, soon moved out.

There is a retreat, even in the allegedly intelligent communities of America, to thinking that it is impossible for someone of color to achieve something significant without the support of government aid. There will always be a pointing of fingers, a false welcoming, and a hushed whisper that proves disingenuous to the message of democracy and opportunity that America preaches.

As a young American maturing in a society that still sees so much from opposite poles of the wealth gap in a racially divided society, I am concerned about the way in which young, black Americans perceive themselves. I am concerned when I hear the “she only got into Harvard because she’s black” whispers trailing me in the hallways. I am concerned when I hear my black peers talking about their accomplishments quietly in avoidance of the imminent panic that signals the neighborhood is, indeed, not being kept clean.

To use Affirmative Action as an excuse for why students of color earn admittance to top schools speaks volumes not about the applicant, but about the person making the comment. I implore of you, dear assuming peer of ours, to rethink your school of thought and to recognize that we are equally capable of finishing first.

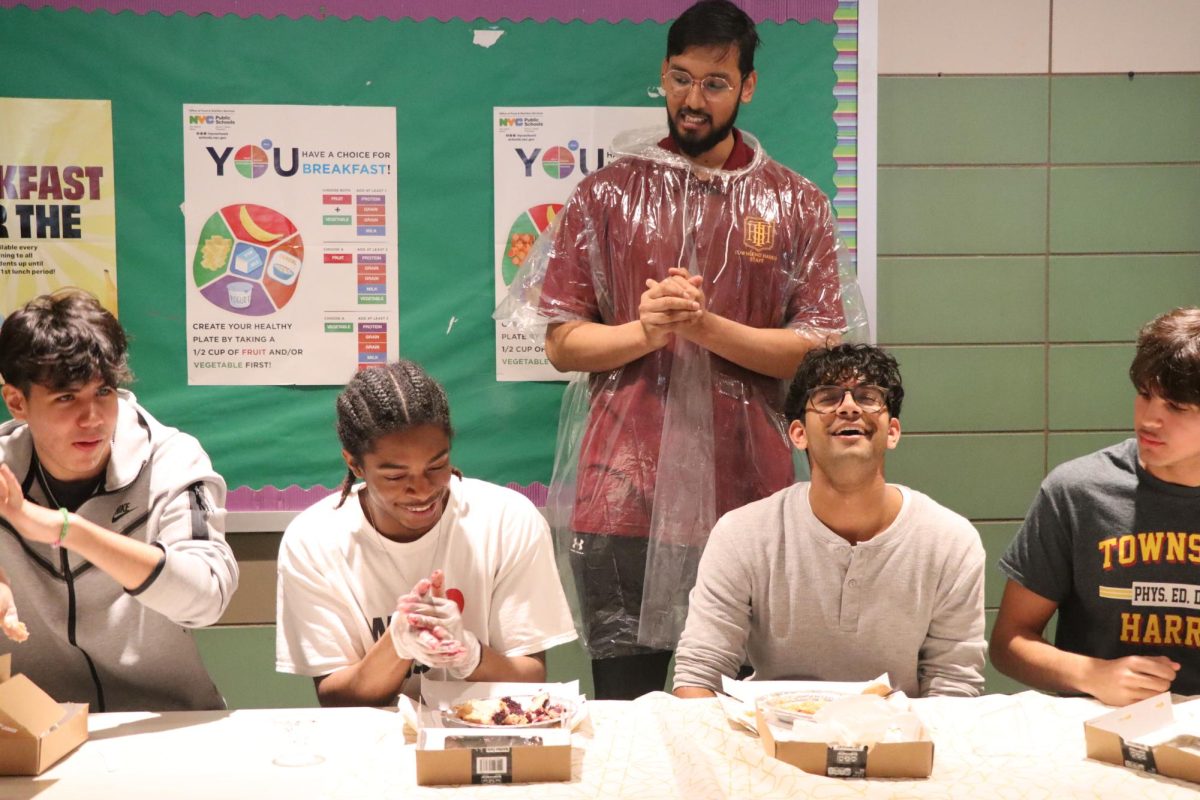

Your comments, no matter how light-hearted they were, are all part of the reason for which the problem still exists. Recognize that students of color can be captains of sports teams, Student Union presidents, directors of school productions, or Editors-in-Chief of publications, and recognize that we (spoiler alert) worked incredibly hard to get there.

Against all odds, from backgrounds plagued by oppression, we can indeed write killer college essays or even win prestigious academic awards.

Our skin may not be the color of porcelain dolls, but there is something beautiful and not so miraculous about a mixed neighborhood that perhaps some of you have yet to understand.