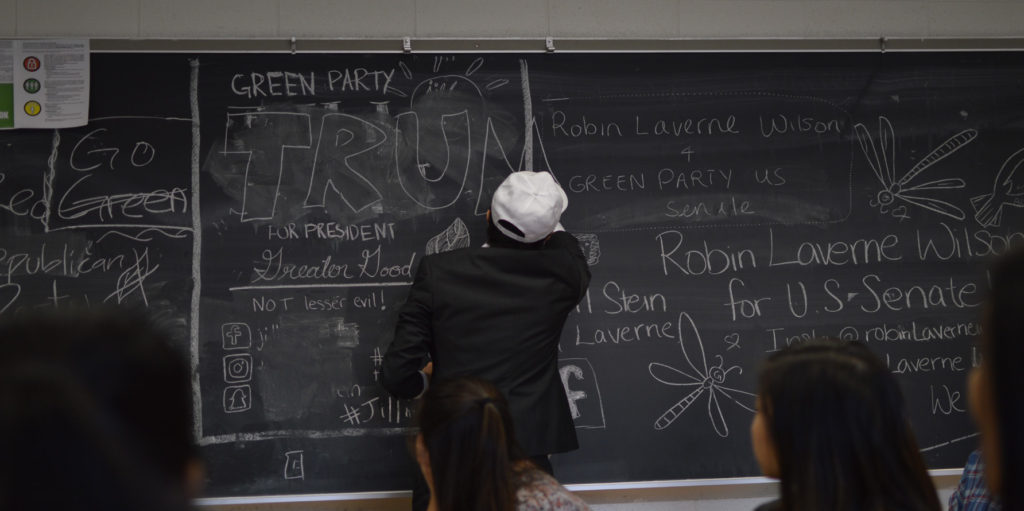

This year marks one of the most controversial races in American history, and students are excited to emulate Donald Drumpf and Hillary Clinton in Townsend Harris’s annual election simulation. Most recently, Donald Drumpf has been under fire in the media for his comments against women, stemming from a tape involving him bragging about committing what amounts to sexual assault. Drumpf has since apologized for his statements, but he has yet to accept responsibility, as he merely dismissed his words as “locker room banter.”

Dismissing conversations about assault as “banter” does incredible harm to victims who already are less likely to speak out when assaulted because of the stigmas associated with coming forward. It already appears that students who are part of the simulation’s Drumpf campaign are treating his accusations as jokes. The third election simulation TV show featured a commercial from Drumpf’s campaign involving the alleged victims of Bill Clinton giving statements about their abuse. They are shown as silhouettes and have their voices altered so as to keep their identities secret. Though it is true that Drumpf could very well fund a commercial like that in real life, the end of the video features an actor exaggerating for comedic effect lines like “[Bill] took my innocence.” Just as the real Drumpf has turned language related to assault into “banter,” students morphed something incredibly dour into something trivial and comical. The rules of the simulation say to “keep it real.” In this sense, they have. But is this year different?

It is important that the student body knows that things are not as playful in the real world and that what Drumpf says has serious implications. The crux of of his campaign consistently promotes more than just this despicable misogyny—it promotes prejudice against several communities. The impact of Drumpf’s words against Muslims, Hispanics, women, and even the disabled is enormous. Mexicans are deemed rapists while Muslims are deemed terrorists —this is enough justification as to why we need to emphasize the impact of his words in this simulation, despite the fact that the political arena seems to have turned a blind eye to the issue.

If we treat these antics the same way we would for any election simulation, we are suggesting that what Drumpf is doing is not wrong, or at least, that it is within the normal bounds of political discussion and debate. Statements cannot be taken casually as if a candidate was simply stating a stance on foreign policy. Students may be unaware of the true context of what he says and how it can threaten us as a community. Today’s freshmen were 10 years old the last time there was a presidential election; should their school package this election as “the new norm” for them?

Beyond the Bill Clinton advertisement, the students working on the Drumpf campaign have largely (and wisely) avoided many of Drumpf’s most controversial claims. In many ways, not presenting Drumpf in as dangerous a light as he presents himself is more of a problem than accurately translating some of his most troublesome comments to the school community.

Since there are always implied rules in the context of an educational setting, a student will most likely not cross boundaries, as offending others will not come without repercussions. Yet, Drumpf has no problem doing so in front of all of America.

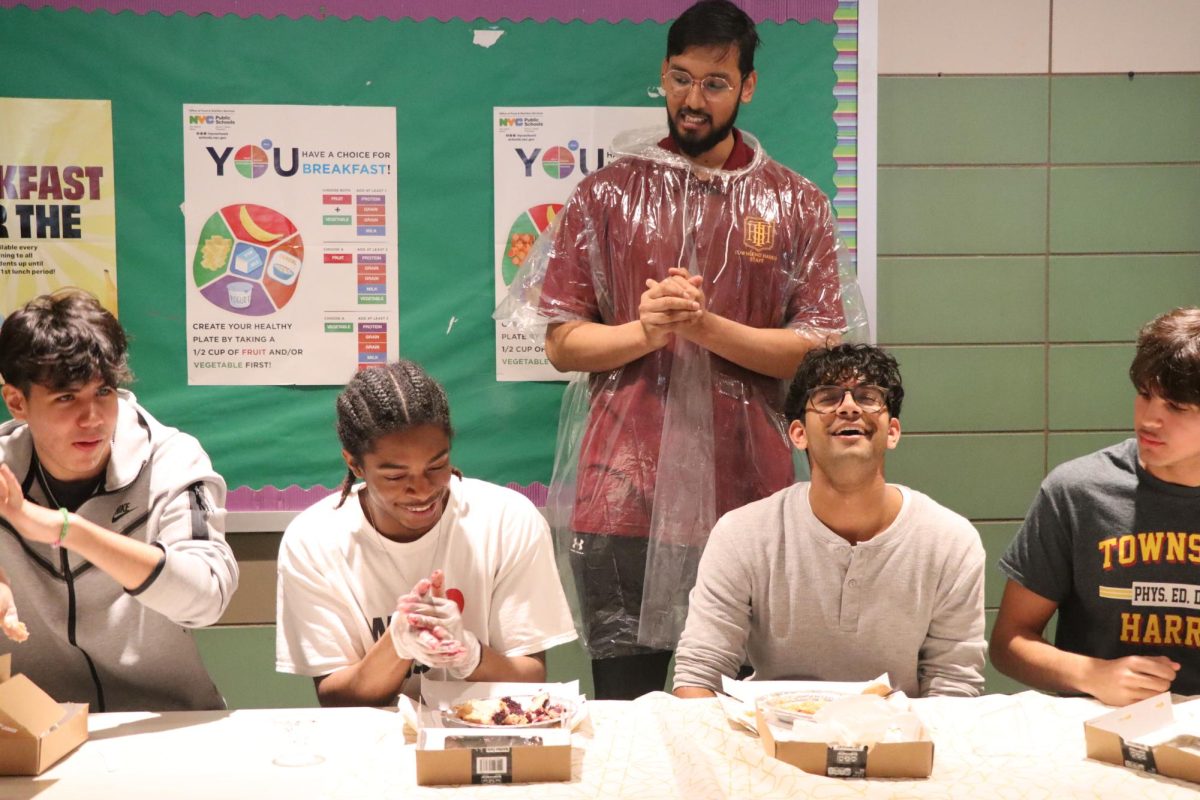

In avoiding some of these other more controversial aspects of Drumpf’s campaign, the simulation instead becomes a game of garnering the most attention to gain the most votes. Candidates willingly make a fool out of themselves to garner a few snickers and giggles from the student body; in many ways, being an enjoyable parody of reality is a better way of getting votes than taking it seriously. This removes the graveness from the situation.

So, when the campaign does depict Drumpf making light of sexual assault and there is no authority figure to step in and discuss it, we risk making such things appear normal. When the campaign avoids his more offensive issues in an effort to avoid offending our liberal and multicultural student body, they risk sanitizing Drumpf himself and making him seem far less harmful than he really is.

The Election Simulation is laudable primarily because teachers let students discover how best to handle controversial topics for themselves and work out real world problems within the confines of school. But when is it time for the faculty to step in and have a larger conversation about what is really going on in America?

This could take the form of an assembly, a lecture from a political science professor at Queens College, or merely a program in class following the simulation meant to contextualize this year in accurate historical terms.

Yes, “stepping in” might detract from the legitimacy of the simulation, but teachers hold the responsibility to make us academically and socially aware so when we are of age to vote, we do so with full knowledge. If students continue to influence students under the premise that the climate of this election is as casual as they are making it seem, we are perpetuating ignorance.

Teachers should thus attempt to clarify that this is not just another simulation—this is a political deformity in our modern day world and it should not be taken lightly